If I had to pick only one place to visit on a trip to Paris, it would be Notre Dame du Travail. What makes it so special? It starts with the eye, but there is more than meets the eye.

Philippa and I had rented a flat on rue de Gergovie in the 14th. On a beautiful mid-December day, I took a walk with no purpose other than to breathe in Paris. The entryway seen above struck me as beautiful, but not in the usual Paris way. It was not a grand entryway for those coming to worship or for tourists “doing Paris churches.”

Quite inadvertently, I had entered Notre Dame du Travail on the path taken by community members seeking a variety of services offered by a living church with a history of strong community involvement. It was a comforting and welcoming entrance. Only later did I understand it a bit more.

I am a historian of technology and design. So naturally some things caught my eye more than others. The rugged details and construction that I associate with industrial buildings were exciting, but at the same time reassuring. As I entered the sanctuary, I felt as if I were coming home, or coming to somewhere I belonged. It was a curious feeling.

I was alone, not in a rush, and the views and details did not intrude too quickly.

Had I come through the grand entryway of the front door, this magnificent scene would have welcomed me. Many things caught my eye, but most of all the strength and grace of the exposed structural steel.

Unhurried, I walked into the church. As I looked back towards the nave, I was captivated by the elegance of all that I saw.

Here I am looking towards the aisle and the front of the church. Details slowly crept up on me as I focused more closely. The elegant lectern held my attention, as did the quiet side chapels with their beautiful artwork.

I grew aware of an art nouveau organ cradled between stone and structural iron. I have a fondness for art nouveau, but it was if I was seeing art nouveau for the first time.

I have since learned more about the church that so captivated me.

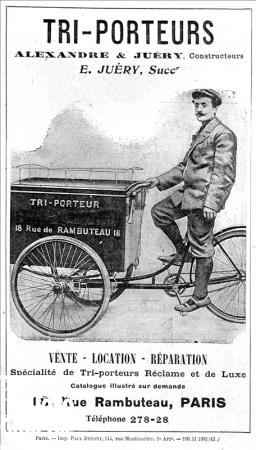

When the Montparnasse Railway Station in the Plaisance quartier opened in 1840, it marked the beginning of rapid growth and change in this part of Paris. The local parish was known as Notre Dame de l’Assomption de Plaisance. When the quartier became part of Paris in 1860, the parish was renamed Notre Dame de Plaisance.

Montparnasse was a gateway to Paris, and the parish struggled to help meet the needs of an ever-increasing number of working-class residents.

Perhaps no one was better suited for the task of leading this growing parish than the abbé Soulange-Bodin, who was appointed vicar in 1884. Twelve years later (1896), he was appointed parish priest (curé) of the parish of Plaisance. Father Soulange-Bodin was clearly a compassionate man with great love for his often poverty-stricken parishioners and a reputation as a crusader for social justice. More important, he could hold a large vision and combine it with a canny understanding of the times.

He asked questions. Why should the 35,000 parishioners who lived and toiled in the centre of industry not have a church befitting them? In a faubourg of 35,000 workers, why not have a church inspired by their workplaces and the materials—iron and wood—that they handled daily? Why not, in anticipation of the rapidly approaching Grand Exposition of 1900, have a church to welcome the many workers who would come first to build it and then to visit it? Why not a national campaign to build a church to honour the workers of France in a parish composed almost entirely of workers?

Indeed, why not? Money came from many quarters.

What about the design? Although the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889, was still controversial in the late 1890s, it had advanced the image of Paris as a city of iron. It had also highlighted those who erected great works in iron. The well-chosen architect, Jules Astruc (1862-1935), spoke the language of inspiring structural ironwork. He embodied the strong links between French architecture and engineering (one reason why Paris has such wonderful bridges). Above all, the new church had to show respect for those who worked with their hands and were often ill-rewarded for their strengths, skills, hard work, and dedication.

Perhaps I was taken by the church because of my background and upbringing (my father was a miner, then later a carpenter and construction superintendent). But that is a small part of the story. It is less about me than about Father Soulange-Bodin, architect Astruc Jules, and the people they served.

Here the dramatic lighting makes an homage to strength and beauty.

From another point of view, the same material seems so soft and welcoming to the warmth of the art nouveau stencil work.

Notre Dame du Travail is much more than 135 tonnes of iron and steel leavened by respect for workplace materials and forms. Father Soulange-Bodin also wanted to elevate and inspire parishioners through other means. Thus the much-admired art work such as that below.

As I walked out of the church, through the door that one might normally enter, I was struck once again by this church as part of a real, living community. From the front door I could see children playing in a playground and I thought of continuity. Yes, these were the children of more prosperous families than those who had once lived here. Many poor families were displaced when the 4,400 lodgings around the Gare Montparnasse were torn down in the 1960s in a bout of “urban renewal.” But new dwellings were built and Notre Dame du Travail still serves many who need help.

As I stood outside the front of the church I wondered how many people walked by its traditional front façade and failed to realize the drama inside. How close did I come to missing it? I had been attracted by a different and, to me, more interesting entryway.

On a later visit to Paris, Philippa and I were at the Gare St. Lazare. As usual, I was wandering about in dreamy contemplation of design, materials and details. As I gazed at the geometric patterns of the dramatic glass and iron roofs I wondered how many of those who built and maintained them had lived in the 14th.

I thought back to another roof and thanked Father Soulange-Bodin and Jules Astruc for giving me the privilege of seeing the material embodiment of his respect for others and me a new way of looking at the roof of a grand railway station.

It was not easy being poor and we should not glamorize it, but nor should we say there is no place for beauty in poverty. In a wonderful railway station, the memory of a church reminded me of the important place that the quest for beauty and dignity occupy in my life.

Let me end with the roof on the inside and the clock (a gift of emperor Napoleon III to the parish for the previous church on the site) on the outside of something I love and I think I understand.

Text and photographs by Norman R. Ball