On a blustery January day, two friends and I set out to walk the route of the Bièvre river across the Left Bank. Jill, who lives in Paris, had done most of the walk before and suggested the route. Elizabeth, a friend from California, and I were up for the expedition, which took a full afternoon. Norman stayed home with a sore leg that needed some rest.

The Bièvre river, a remnant of Paris’s industrial past, was buried in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, having become polluted from the many tanneries and dyeworks along its route. Tanneries used substances such as dog poop (known, oddly enough, as pure) to soften leather, while dyeworks in the 19th century were using more and more chemical colourings. (I should know. My great-great-grandfather, who trained as a chemist in Switzerland, ran a dyeworks in Lancashire in the 1860s that poisoned the river Irwell near Bacup. Environmentalism was not a thing back then.) This 1862 photograph by Charles Marville makes it all look rather tranquil. Note the rudimentary bridge.

The three of us met in front of the Jardin des Plantes. The garden was closed because of high winds and the danger of falling branches. We noticed several people approaching the gates, reading the sign, and rolling their eyes. One of them muttered “Typical…any excuse to close” before stomping away.

Jill had brought a book about the buried river that had a not-terribly-detailed map of the route with very small type. Actually, not having a precise guide added to our enjoyment, as we had to keep our eyes open for the medallions in the pavement that mark the route.

We got off-track sometimes, but the triumph of spotting a medallion indicating the correct route was very satisfying. Every so often, we would also find square plaques on the ground indicating other features of the river.

Our initial exploration went well until the road dead-ended. The route disappeared underneath the buildings of the natural history museum, a green campus that looked interesting, but was closed to the public. We did ask at the gate, but the guard suggested we keep walking.

I took a picture of the pathway, wondering if the leaf litter concealed any medallions.

Eventually, we spotted medallions on the rue Saint-Hilaire. The gap between the buildings suggests the route.

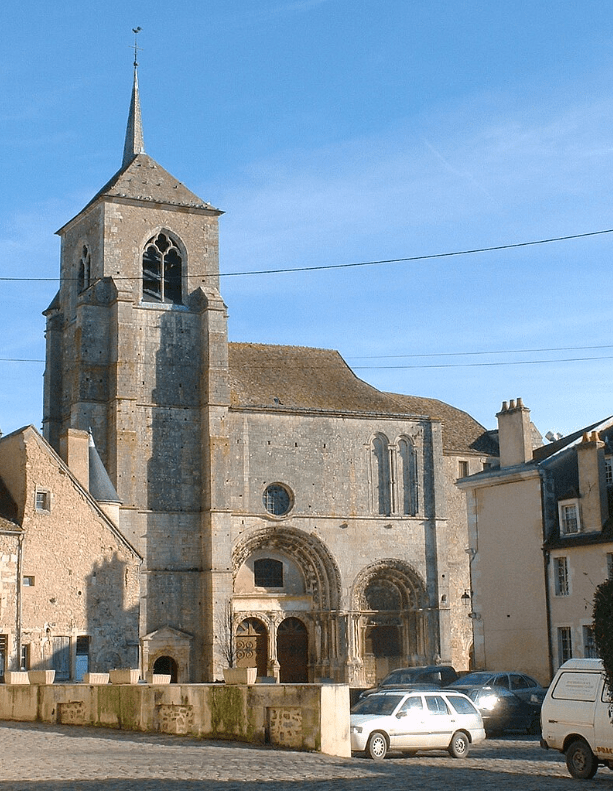

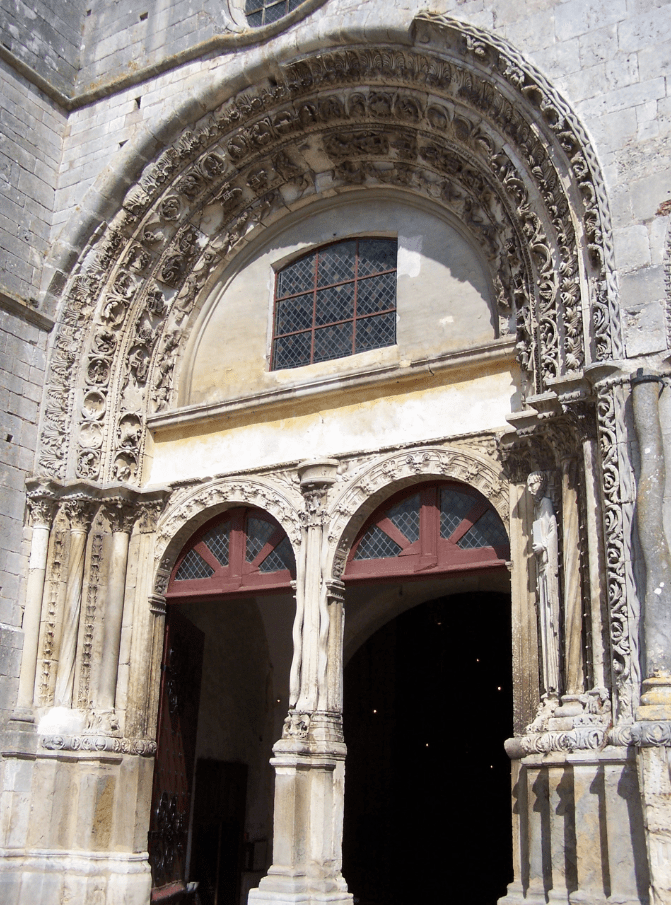

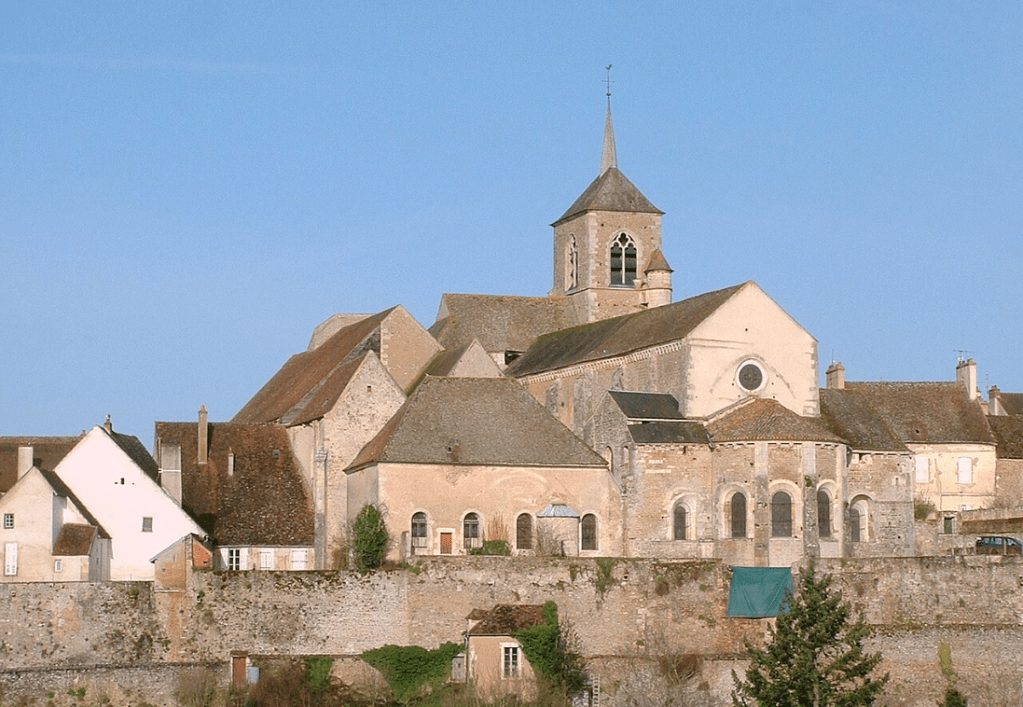

On the other side of the road, however, was a solid wall of buildings. We picked up the trail again near the church of St. Medard at the bottom of the rue Mouffetard. At this point, we stopped for a snack in a pastry shop while a rain shower passed overhead. I had a “lingot,” which is similar to a “financier” but a slightly different shape. Highly recommended.

When the rain stopped, we pressed on, leaving the 5th arrondissement and crossing into the 13th. The rue Berbier du Mets was studded with medallions, as we wound our way past the back of the Gobelins tapestry factory and the chateau of the white queen (chateau de la Reine Blanche).

Actually, there were two white queens. Marguerite de Provence, widow of Louis IX (also known as Saint Louis), built a castle here in the 13th century when her husband died. Royalty wore white as a symbol of mourning. Her widowed daughter, who was actually called Blanche, lived with her. The current building is not the original 13th-century construction, but dates from the 15th to 17th centuries.

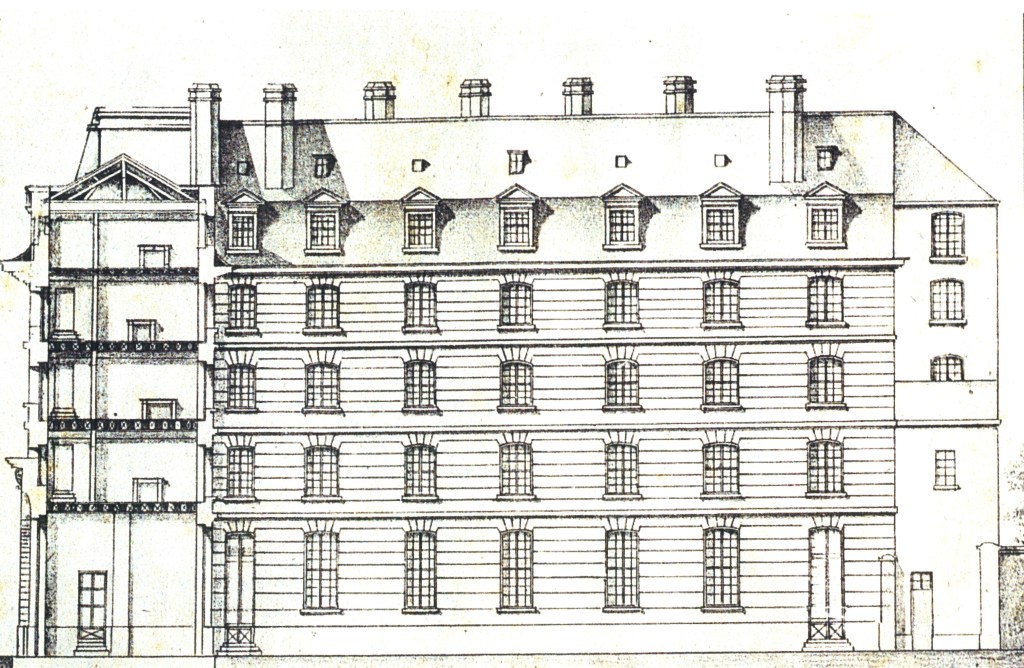

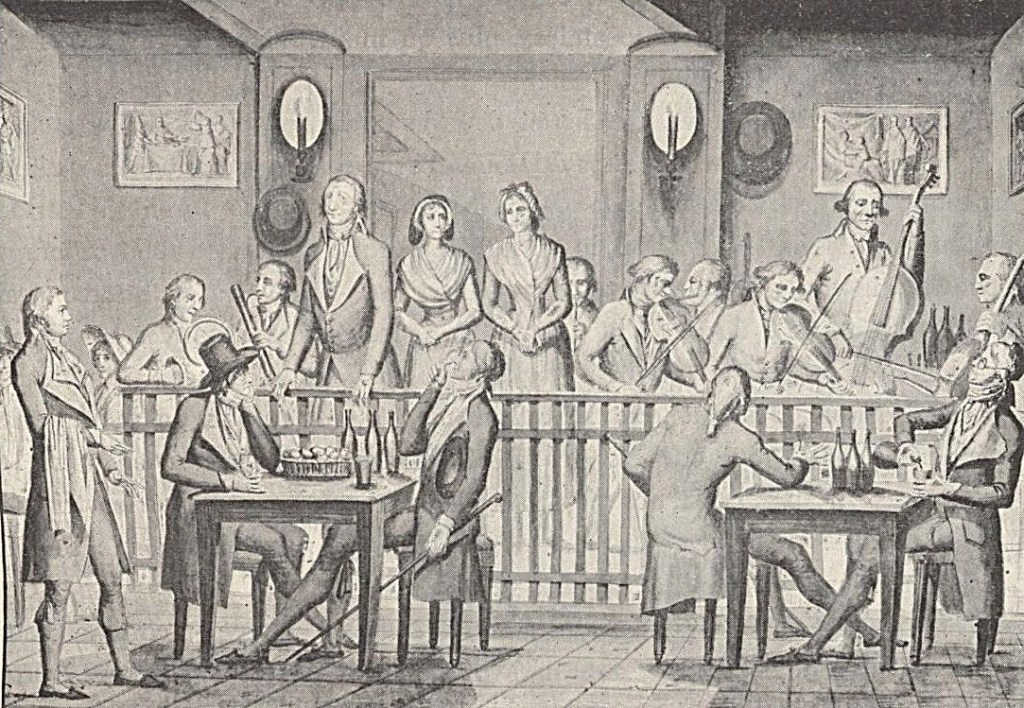

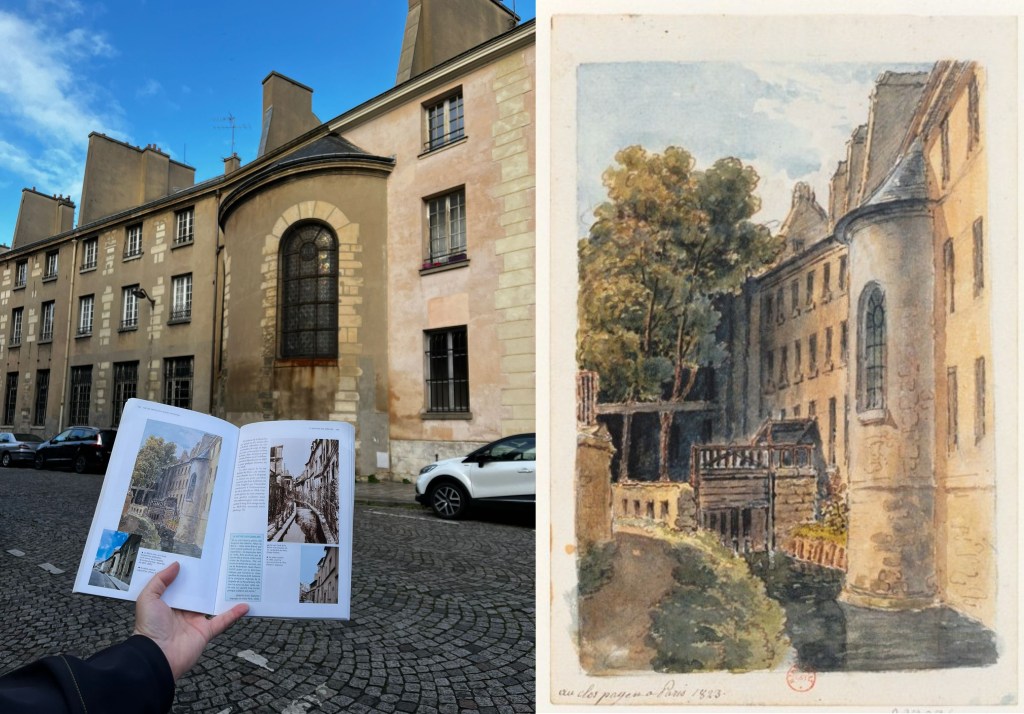

As we walked along the rue Berbier du Mets, Jill showed us a page of her book: an old painting of a tower at the back of the Gobelins tapestry factory rising up from the riverbed. Sure enough, the tower was still there. Comparing the picture with real life gave us an indication of how high the ground had risen over the buried river.

The route skirted the Square René Le Gall, a pretty sunken park that seemed very green in January (at least to Canadian eyes). We followed the medallions along the rue Croulebarbe to the boulevard Auguste Blanqui, crossed, and immediately lost the trail.

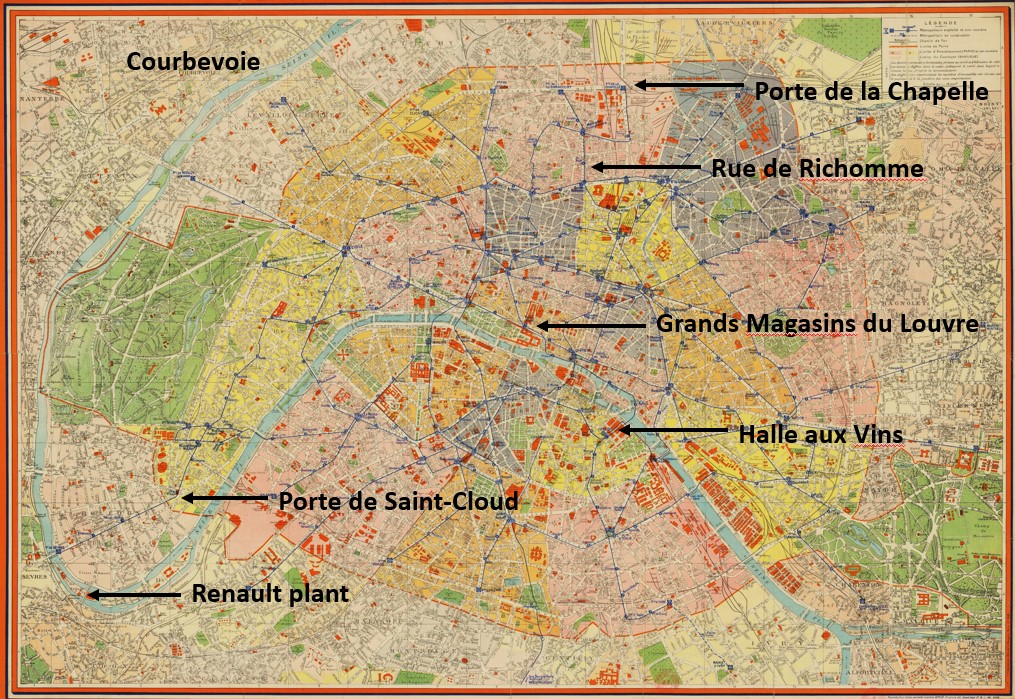

At that point, we discovered another problem with the map that we hadn’t spotted at first. There are two branches of the river, the bras vif (living arm) and the bras mort (dead arm) – the dead arm being part of the river that had stopped flowing before it was buried. We’d hoped to follow the bras vif, but we kept finding medallions for the bras mort. Then we noticed that whoever had designed the map had indicated the bras mort with a lively blue, and the bras vif with a dull mauve. That seemed counter-intuitive. We’d been following the bright blue line by instinct, and by mistake.

We picked up the trail again on the rue Wurtz and followed the river’s oxbow route, stopping to explore the Cité Florale. This urban village is a collection of small houses on narrow streets named for flowers.

Shortly after passing the place de Rungis we spotted a sign with the name Bièvre (it seemed to be a space for children’s art), which encouraged us, as we could not see any medallions nearby.

Jill and Elizabeth were starting to notice my tendency to wander into any courtyard with an open or unlocked gate. I cannot help myself. Many are open because there are businesses in the buildings that need to be accessible to clients and customers. And some are simply open because nobody has locked the gate. You never know until you walk in. The worst that can happen is an abrupt invitation to walk out, but nobody paid any attention to us.

We found one courtyard dominated by a huge tree, with Christmas decorations on it and on the greenery around the courtyard.

Approaching the circular Place de l’Abbé Henocque, we got a little lost. Looking at Jill’s map again, we saw a line in orange. The legend said that it represented a “dérivation à ciel ouvert.” Really? Open to the sky? We had to investigate.

What we found was another urban village of small houses on three pedestrian streets arranged in the form of a triangle, called the Square de Peupliers. I guess a triangle can be a square in Paris. We saw a man clipping a tree in his front garden. He waited for us to pass, and I asked him if he knew where the route of the Bièvre was. He looked mystified.

A few minutes later, we found several medallions in the area, but no sign of an open waterway. I wanted to find the man and show him, but he had disappeared.

The route then turned south and headed for the edge of the city. The streets in the area, many of them named for doctors, were very different from those in central Paris. One, with houses set back behind small front gardens, reminded me of London.

We noticed a lovely rainbow as the sky began to clear.

We lost the trail of medallions around the time that we crossed the Petite Ceinture.

But when we entered the Parc Kellerman, it didn’t matter. The spacious park is attractive, despite the constant noise from the Periphérique on its far side, and we were treated to a splendid sunset.

As it was getting dark, we made our way back to the Porte d’Italie for a glass of mulled wine and some snacks. Jill calculated that we had walked about 10 km.

If you are in Paris, I can recommend the walk. No need to do it all, you can do a section and still enjoy the hunt for medallions. I love the way it took us through some unfamiliar areas we might never otherwise have seen, and the scavenger-hunt feeling of searching for clues along the way. Jill says she’s already planning a new walk for our next visit.

Parts of the Bievre river outside Paris are being uncovered (a process called daylighting), and there are plans to open up more of the river.

Text and most photographs by Philippa Campsie; photograph of Gobelins by Elizabeth Symington; watercolour of Gobelins from Wikimedia; Marville photograph from the Met.

Further reading: Renaud Gagneux, Jean Anckaert, and Gerard Conte, Sur les traces de La Bièvre Parisienne, Parigramme, 2002.