Toronto has recently completed a Ward Boundary Review, its first since, oh, 2000. City councillors were concerned that some wards had far more voters than others. Population was growing downtown and declining in the inner suburbs. After 17 years, Something Had to Be Done.

How about 157 years? That’s how long Paris’s arrondissements have been in place. Population is declining in the centre and growing around the edges. The Paris mayor, Anne Hidalgo, also feels that Something Needs to be Done.

But before considering what that might be, let’s look at the previous arrangements of the city, working our way back in time.

The current shape and configuration of Paris dates from January 1, 1860, when the City annexed a series of surrounding villages and established 20 arrondissements. The numbering started in the centre and spiralled out from there. Previously, the city had been smaller and had had only 12 arrondissements.

Why the spiral arrangement? The story goes that the well-to-do inhabitants of the villages to the west, Passy and Auteuil, which were to be incorporated into the new city, found out the plan for numbering would put them in a new 13th arrondissement. This was simply not acceptable. Not for reasons associated with “unlucky 13,” but because of a common expression: “se marier à la mairie du 13e” (getting married in the 13th). When there were only 12 arrondissements, this reference to a non-existent arrondissement meant living together without marriage. Horreur! The mayor of Passy suggested the spiral (escargot) arrangement, and the idea prevailed. The number 13 was safely transferred to the less-well-off southeast sector.

The pre-1860 arrangement of 12 arrondissements in the smaller city is visible on this map from 1809. You can follow the link and zoom in to see remarkable detail.

A simplified version from French Wikipedia shows the component quartiers.

The 12 arrondissements were numbered west to east, 1 to 8 on the right bank, 9 in the middle, and 10 to 12 on the left bank. The configurations are downright peculiar. Arrondissements 3 and 5 consist of two discontiguous chunks (there’s a story there, no doubt, and the word “gerrymandering” comes to mind). No. 6 is in a sort of dogleg shape. Nos. 1, 8, and 10 are huge. All around the edge were the walls and the “barrières.” These were pre-Revolutionary customs houses where officials collected tax on goods entering Paris.

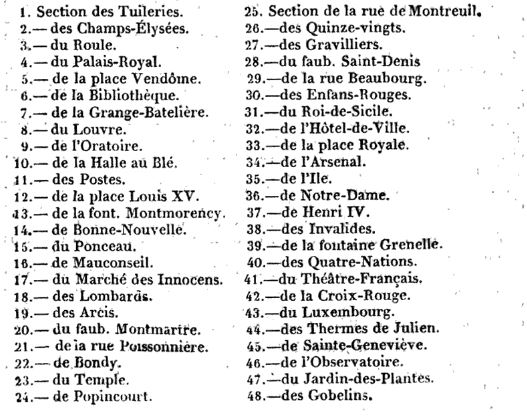

This configuration dates from the Revolution, when the Republican authorities were remaking everything from the city to the calendars: the law creating the new organization was passed on 19 vendémiaire in Year 4 (11 October 1795), but the organization of the city into 48 sections was originally done in 1790. The new sections were given traditional names at first:

But as the Revolution wore on, many were renamed to remove all traces of royalty and the church. Who in the 1790s wanted to live in a section named for Place Louis XIV? It became, first, the Section du Mail in 1792 and then the Section Guillaume-Tell in 1793 (chosen because William Tell had a reputation for opposing tyrants). The Faubourg St-Denis became the Faubourg-du-Nord and the section Ile-St-Louis became the Section de la Fraternité. And in a what-were-we-thinking moment, the Section Mauconseil became the Section Bon Conseil (meaning “good advice”). There were so many name changes (a few districts went through three or four names in the early 1790s) that one wonders how anybody found their way around town.

To add to the confusion, houses were numbered. Earlier attempts to do this had foundered when aristocrats refused to assign anything so banal as a house number to their mansions. But in 1790, the revolutionary government was in a position to insist and the aristocrats were, ahem, otherwise engaged. However, the task was assigned to leaders in each of the 48 sections, and not surprisingly, each one went about it differently. The mess was not sorted out until 1805, when a law established a numbering system to be used uniformly throughout the city.

(By that time, most of the Revolutionary names were gone and many of the historic names had been re-established, as the French Wikipedia map indicated.)

Going farther back in time, what preceded the revolutionary sections were the quartiers of the Ancien Régime. Interestingly enough, there were 20 of them in the 18th century, although spread over a much smaller area than today. This 1705 map from Gallica shows them all. (Again, best to follow the link so you can zoom in and look around – the detail is amazing.)

A list in the bottom left-hand corner helpfully indicates the origin of the 20 quartiers. Four date from time immemorial (“dont le temps est incertain”), another four were added when Philippe Auguste expanded the city in 1211, eight more were added by Charles VI in 1383, one was added in 1642, and finally three more in 1702.

Those four original central quartiers – Quartier de la Cité, Quartier de St-Jacques de la Boucherie, Quartier St-Avoye, et Quartier de la Grève – lie underneath the many overlays of other systems. The Ile de la Cité is now divided into two (one part in the 1st arrondissement; the other in the 4th), the Tour St-Jacques is all that remains of the former church of St-Jacques de la Boucherie, the Quartier St-Avoye has kept its name and is part of the 3rd arrondissement, and the Quartier de la Grève is the area around the Hotel de Ville and St-Gervais.

And now the mayor thinks it’s time for change. In 2015, she opened up the possibility of completely redrawing the map to reflect the ever-decreasing populations in the small arrondissements in the centre, and the much bigger populations of the large outer arrondissements, which were still partly rural and sparsely populated in 1860 and have now filled in. It was a controversial idea, to say the least.

A complete redrawing seems to have been ruled out – so far. On 16 February 2017, the Assemblée Nationale passed a bill consolidating the first four arrondissements (the oldest part of the city) into one electoral district of more than 100,000 inhabitants; this is less than half the population of the 15th arrondissement, for example, but more than twice that of the 6th or the 8th. So much for electoral parity. The four will remain as separate postal districts (whew, no need to reprint the letterhead), but many municipal services will be consolidated. There will be one arrondissement mayor for the consolidated area, to be elected in 2020.

I wonder – in which mairie will the new mayor take up office? And what will happen to the other three mairies? (The Hotel de Ville insists that other civic uses will be found for them all.) The oldest is that of the second arrondissement, on the rue de la Banque, which dates from 1848 (it began life as the mairie of the former third arrondissement). The other three opened in the 1860s and have always served in their current functions. My vote would go either for the 1st, which has a lovely rose window…

…or the 3rd, which has a handsome courtyard and faces a park.

Between now and the municipal election in 2020, there are many decisions to be made. The mayor has planned for consultations (conférences citoyennes) with the inhabitants of the four arrondissements. Some unhappy legislators who did not approve of the change are vowing to continue the fight, depending on the outcome of upcoming legislative elections. On to the future or back to the past? Parisians will decide.

Text by Philippa Campsie, images from Gallica and Wikipedia.

Recent elections saw the Socialists losing ground.

Pingback: »Blog Archive The Snail! -