I love bridges and cannot imagine Paris without them. In Paris I gaze at them, linger on them, and take photographs. At home I remember them fondly. But of them all is there one that I love the most? Oh yes. And although I am a historian of technology, my favourite is modern, very modern: la passerelle de Solférino (the Solférino pedestrian bridge, recently renamed the Léopold Sédar Senghor bridge), which opened in 1999.

This superb design by engineer-architect Marc Mimram (born in Paris in 1955) links the Jardin des Tuileries to the Musée d’Orsay. It is fitting that the bridge upon which pedestrians walk to and from a former tileworks (now a garden) and a former train station (now a museum) should itself be a superb work of industrial and engineering art. For this bridge Marc Mimram was awarded the coveted architectural award, Equerre d’Argent.

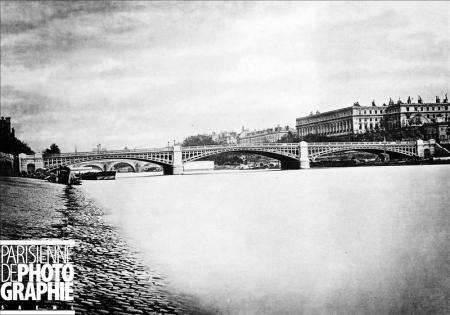

Mimram’s is the third bridge at the site. The first opened in 1861 to celebrate Napoleon III’s 1858 victory over the Austrians at the Battle of Solférino. It was a handsome three-arch cast-iron bridge, which carried vehicles and survived the ravages of the great flood of 1910.

But in a busy commercial river at a relatively narrow spot, the abutments for the bridge sometimes got in the way of heavily laden barges (péniches). After decades of collisions, the bridge had become dangerously weakened (fragilisé).

The photo below, taken on April 26, 1961, shows the about-to-be-demolished original bridge with the “temporary” replacement dominating the foreground.

“Temporary” is a relative term, not an absolute one. For three decades, this undistinguished structure allowed pedestrians to cross the Seine at one of its most beautiful points. It was finally demolished in 1992. What did the 30-year-old “temporary” bridge say about Paris?

We all read designs and our environments differently. I find the temporary bridge more than merely ugly and unimaginative. It reminds me of the countless pedestrian overpasses I have driven under on expressways that cut through neighbourhoods where the locals don’t count politically. Or where politicians and engineers have insisted that ugly = efficiency + value for money. In some places, people really believe that ugly means their tax dollars are being well spent.

Whatever the reason for its uninspired design, whatever the reason for its longevity, the second bridge seems alien in design-rich Paris. It looks neither Parisienne nor respectful of those who must look at it and cross it. To be fair, the bridge did do what it was designed to do: it allowed people to walk from one side of the Seine to the other. However, if you look carefully, you will notice that both the bridge of 1861 and that of 1961 only joined the tops of the embankments. To get to river level, one took the stairs.

Mimran’s passerelle de Solférino changed many things. It crossed the Seine in one leap, so there are no abutments to bump into at river level. And it joins four points, not just two: water level on both sides of the river and the top of the embankment on both sides of the river. And it makes the journey visually interesting.

Here we are beginning to walk from water level to the top level as one prepares to cross the Seine.

As one approaches the bridge, one is struck by the richness of detail. I saw other users of the bridge lingering to examine the details, just as I have on other bridges that have been designed to let us appreciate being alive rather than just letting us get on with the next job.

The details, precision, and lightness of material reminds me of aircraft engineering. As I walked across, I thought about airplane structures and the innards of a jet turbine engine I had recently seen and admired.

But as our pedestrian crosses (alas, the famous yellow raincoat is no more: it was later stolen – in Toronto), what awaits her?

Having arrived at river level, she might take the stairs in front of her to cross under the traffic and emerge in the Tuileries gardens. Or she might choose to stroll along the bank.

Or our pedestrian could have done what this bridge was really designed to do. And to appreciate this fully, follow this link (view it full screen). It’s not just a bridge to look at, but a bridge to look from.

I regard this bridge as a reaffirmation of the long tradition of aesthetic excellence and sensitivity amongst French bridge engineers (the bridge designs of Gustave Eiffel are a good example). This tradition is deeply rooted in their best educational institutions and widely visible. Such sensibilities are absent in many countries.

But designs such as the passerelle Solférino could not have been done without computer-assisted design methods, linking the best of tradition with the best of technology. Furthermore, as if in rebuke to those who associate ugliness with efficiency, the bridge makes very economical use of materials (steel and wood).

Marc Mimram has a clearly expressed philosophy of design and aesthetic sensibility, along with the talent and good fortune to put it to use. For a quick introduction go to his website and click “Agency.”

The page is worth reading and rereading carefully. Note that he is described as both architect and engineer: this combination is exceedingly rare.

One reads that “We have always considered that architecture cannot remove itself from the field of construction and that the execution is equally a determinant for a project as it its conception.” In other words, don’t design it if you don’t know whether it can be built. (You’d be surprised how often this happens with professionals.)

More important, he is not talking about structures in isolation, or on a computer screen, but structures as part of our lives and the space we occupy. “A bridge is not just a connection, a road, not just an asphalt strip accommodating migratory traffic.” He adds that when one thinks of and works within “local scale” and “an informed historical geography,” then “the bridge becomes a balcony for a stroll on the river, the road a passage through the features of geography.”

Well isn’t that curious? Most of the bridges I experience as a pedestrian make me feel I am simply a legally required nuisance, and the roads on which I drive seem designed to feel and be the same, no matter what the local geography.

Mimram speaks of the sin of designing in which saving time takes precedence over all else. “To avoid the errors of yesterday, it is necessary that these major transformations not be reduced to their technical values; we have to find the qualities that are sensible to the consideration of the project’s landscape, the constructed qualities of structural works, and the qualities sharing the public forum.”

He warns that we lose much if we think of the city solely in terms of “mathematical imagery” and adds that “conversely, it is the attention to places, the value of light, and the pleasures of gravity and material that are put in place that assure the generosity of shared space.”

Ah, the “generosity of shared space.” That, I think, more than anything else, is what I find so intriguing and beguiling about Paris. There is privacy, but there is much shared space. And when I stand on the passerelle Solférino I am sharing space, views, and perhaps even conversations. This is not just city life, this is life.

Text and original photographs by Norman Ball

Further reading: Marc Mimram — Minimal Design: Solferino Bridge in Paris, by Francoise Fromonot

Click here to watch an interview with Marc Mimram (with English subtitles). In it, he discusses the use of new materials, such as a new form of concrete called Ductal.