It’s January, and the papers are full of recommended diets to deal with the extra pounds we all gained over Christmas. Oh, phooey. I’ve got a great book on French food that is making me hungry just reading about it and my niece Alex has started a recipe project and blog and invited contributions. Forget the diet, there is cooking to be done.

I’ll start with the blog. It’s very new still, but Alex has committed to trying one new recipe a week for the whole year, and my sister and I are weighing in with our ideas, along with some of Alex’s friends. So do drop by and take a look: it’s called Eat and Two Veg.

As for the book, it’s by two people we have never met, but with whom we have a lot in common. Diane Shaskin and Mark Craft are a husband-and-wife writing team, just as Norman and I are. They are Canadians who are indifferent to hockey and have no objection to green Christmases. They travel to France as often as they can. And when a friend asks “You’re going back again?…Haven’t you been there, done that?” Diane’s response is, “I haven’t been to France for six months…I mean, it’s perfectly obvious, isn’t it? Think of all the things I’ve missed during those months. Parisian life is going on without me!”

But of course. Why go anywhere else? You can find new places, have new experiences, voyage into the unknown, without leaving Paris. And at the same time you can enjoy familiar scenes, revisit old haunts, and rejoin friends. The perfect combination.

Diane and Mark’s book is called How to Cook Bouillabaisse in 37 Easy Steps: Culinary Adventures in Paris & Provence.* Don’t let the title scare you. It’s sort of a journal/scrapbook/cookbook. There are short chapters on Diane and Mark’s experiences dating back to their first trip to France 20 years ago, brief explanations of various French foods, memorable menus, preparation tips, photographs, a list of Provençal markets, and a directory of favourite Paris restaurants. And plenty of non-intimidating recipes.

The two of them rent places in Paris and Provence. What a relief. I’m not sure I could stand one more book about non-French people buying and fixing up a tumbledown house in France and dealing with dire construction problems and impossibly quaint local tradespeople.

Diane and Mark shop at markets and cook things, they eat at restaurants and bistros, they take tours and courses, they make mistakes and learn from them, they ask questions when they don’t know something. And they have studded the book with the useful things they have found out.

Item: “Tom’s Coquilles St-Jacques has the red foot [of the scallop] attached, which is common in France to assure the diner that the scallop is genuine and not a cut piece of cod.” (p. 22) I remember seeing that little orangey-red thing on the scallops that our friend Marie brought us on a recent visit, but I didn’t know why it was there.

Item: “Butter in France has an AOC, Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée. Two of them.” (p. 121) You don’t say.

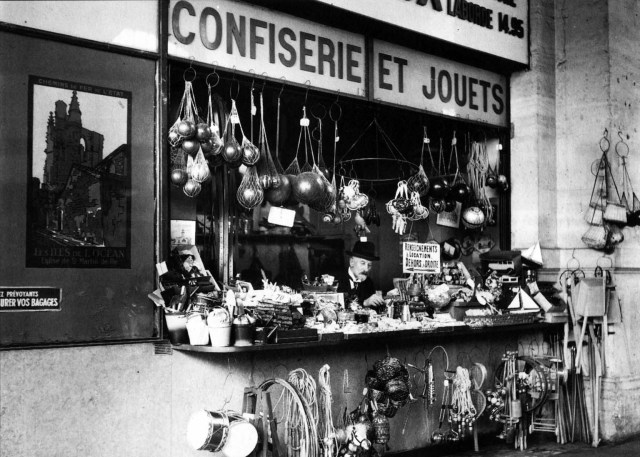

Item: Market vendors indicate the quality of the produce with three categories. “Extra means best quality: no bruising, no spots, perfect. Catégorie 1 means good quality with little bruising. Catégorie 2 is everything else, still good product, but perhaps suitable for cooking or preserving.” (p. 185) Something to remember next time we’re at the market.

Item: In making a green salad, after washing the greens, “spin several times to make sure the majority of water is removed. Water is the enemy of crisp salads…[then] place the greens in the refrigerator for at least 15 minutes. This guarantees that they will become crisp.” (p. 191) Something I will remember. (Norman wants me to add that he never spins salads, he blots the leaves dry with a clean towel. He says he read in an article about French chefs that this is how it should be done. And he can’t wait 15 minutes!)

All in all, an informative and enjoyable read. And despite the title, it is not confined to Paris and Provence. There’s the visit to the Champagne region. And the trips to Hanoi to adopt a little boy, complete with a couple of Vietnamese recipes.

My copy is now studded with yellow sticky notes of recipes to try. I guess eventually I can add them to Alex’s blog.

Text by Philippa Campsie, photographs by Norman Ball.

*Diane Shaskin and Mark Craft maintain Paris Insiders’ Guide, a compendium of information for travellers to Paris. Their book is available from Amazon.