In a sense, all postcards are a form of advertising. Some advertise the sender’s good fortune or superiority: “Hi. I’m here. You’re not.” Others advertise the attraction itself: Kozy Kabins in Niagara Falls, the highest rotating restaurant west of the Mississippi, or the world’s only combined alligator-and-ostrich farm.

I prefer the more traditional product ads, particularly those from Paris. Consider the one below.

I am fond of this card for several reasons. The subject, L’Église Sainte-Marie-Madeleine (the church of Saint Mary Magdalene) in the 8th arrondissement at the end of rue Royale is a beautiful building. Often called simply La Madeleine, it has a complicated history.

The spot on which is stands was once the site of an early synagogue, seized by Bishop Maurice de Sully in 1182. This was the beginning of a centuries-long tale of various attempts at building, a succession of architects, most of whom tore down their predecessors’ works.

Napoleon’s 1806 decision to build a Temple to the Glory of the Great Army led to a new round of architects, designs, more tearing down of various bits, followed by a loss of focus when the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel was completed in 1808. Then Napoleon lost his job in a hostile takeover.

During the Restoration, Louis XVIII decided the structure should be a church. More architects, more competitions, more demolitions, and continuing confusion. In 1837, when trains were the coming thing, someone suggested turning the building into a train station. But reason (or faith) returned and it was consecrated as a Roman Catholic Church in 1842.

The interior is stunning, but I am particularly taken by the august exterior of this Neo-Classical style building. With its 52 Corinthian columns, each 20 metres high, it does not seem pretentious, but dignified, reassuring, correct. Even with the traffic that roars about it today, I find it calming just to be near it.

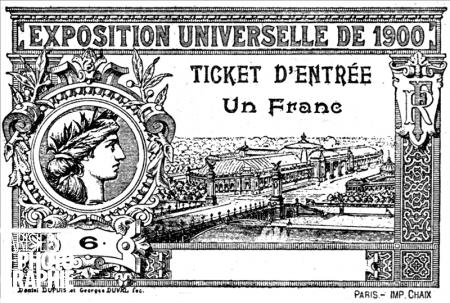

The card above was designed for and printed at the International Exposition in Paris in 1900. It reveals another religious connection. Or an advertisement. Look at the lower left: BENEDICTINE. The Benedictine monks of Fécamp were pioneers in the European liqueur industry. On the address side of the card is a beautifully designed and printed ad. Subtle. I like it.

The image below is from the same Exposition. I love the detail and the sense of perspective, which leaves room for writing, a reminder that at one time it was forbidden to put your message on the address side of the card. In the background to the left, we see the familiar Eiffel Tower built for the 1889 exposition and the more short-lived giant Ferris wheel built for the 1900 Exhibition.

The building with the turrets facing the river is the Palais de Justice, whose list of involuntary “guests” includes Marie Antoinette, Robespierre, and Napoleon III. If you look carefully on the bridge, the Pont de Change, you will see my first initial in several places. Alas, it does not stand for Norman, but for Napoleon III, who had it built as one of his many projects to modernize Paris. Look at the other side of the card.

This is even subtler than a fine bottle with ribbon and medal. It is the wrought-iron fountain in the Benedictine square in Fécamp. In this town, Alexandre Le Grand “rediscovered” the Benedictine Liqueur recipe originally created in 1510 by the monk Dom Bernardo Vincelli. If you are 18 or older, you may sign into this website to learn more.

But men and women cannot live on Benedictine alone. If you go to Paris, you’ll need a place to stay.

The card above advertises the Hotel Régina on the rue de Rivoli. It exists today under the same name. Philippa and I have walked by it many times. This card was issued to announce that it would be opening soon, 112 years ago: the first of March 1900, to be exact.

Or you might prefer the nearby Grand Hotel du Louvre.

It, too, exists today. Over the years, the hotel has had quite a roster of guests. The painter Camille Pissarro took up residence there in 1897, Sigmund Freud dropped in while writing about Leonardo da Vinci. The hotel and the atmosphere of the area influenced Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes tales.

The sense of continuity is part of the fascination of learning more and more about Paris. The Hotel du Louvre has been at its present site on the Place du Palais Royal since 1887. There was an earlier hotel of the same name, dating from 1855, a luxurious haven of 700 rooms and a staff of 1,250 on the other side of the Place. But by 1887, the Louvre was expanding, as were the major department stores, and the hotel had to move to a new building across the square. The original hotel still stands and one can visit the many shops and galleries in the Louvre des Antiquaires, 2, place du Palais Royal.

One might ask why such a fine hotel was relegated to such a relatively small image on the post card. The answer is on the back.

There is a clearly marked place for the postage stamp and a warning that that side of the card is to be used exclusively for an address. The message must go on the front, with the picture of the hotel. So space must be left below the image.

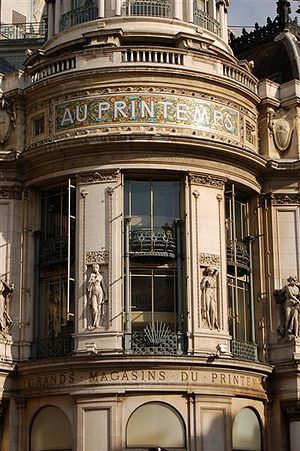

No advertising card that I own says more about continuity of Paris institutions than the one shown below.

The text in French and English provides a wonderful bit of Paris culinary history. La Tour d’Argent at 15, Quai de la Tournelle, in what is now the 5th arrondissement was founded in 1582 during the reign of Henry III as an inn next to a monastery. It got its name from the silvery stone used to build it. The combination of fine food and an equally fine view of the Seine and Notre Dame made it a favourite of the royal court.

Remarkably, it has continued as a popular restaurant. When Julia Child ate there one night in the early 1950s, she described it as “excellent in every way, except that it was so pricey that every guest was American.”

As the postcard indicates, it had merged with the Café Anglais, another venerable name in Paris culinary history. This café opened in 1802 and the name celebrates the Treaty of Amiens, which represented a brief suspension of hostilities between the warring English and French. Initially, it was a downscale eatery for domestic servants and coachmen. Located at 13, Boulevard des Italiens, it attracted the theatre crowd and eventually found favour with the higher levels of French society. It closed in 1913; the original building no longer exists. Instead, it became part of la Tour d’Argent, which also had risen to the highest culinary ranks.

In the mid 19th century, Frédéric Delair became the owner and formalized the famous duck recipe. He was so confident of the quality of his duck, that he numbered each one. Surely a high point in the history of culinary one-upmanship.

I doubt that Philippa and I will ever savour a numbered duck (the number is well over a million by now). However, we have many fine memories of food and drink in Paris. One afternoon, we chatted over wine in the café on the second floor of the Nicolas store that overlooks the Place de la Madeleine.

We admired the church opposite us and watched the traffic inch along. How I wish we could have overheard the two men deep in conversation as one scratched his head and the other buried his face in his hands.

But mostly we enjoyed the view of la Madeleine and the calm of those who know how to slow down.

Perhaps next time we will order a glass of Benedictine and raise a toast to the creators of early advertising postcards.

Text and photographs by Norman Ball.