Here’s a question for contestants in a game of “Connaissez-vous Paris?” How many railway stations are there in Paris?

Most people would say six: St-Lazare, Nord, Est, Lyon, Austerlitz, and Montparnasse (the original version of this station is shown above). Some might add the station-turned-art-gallery of Orsay and call it seven. I might have given one of those answers myself, until I ran across a book called Paris et ses 50 Gares (Paris and its 50 stations).*

Fifty? Really?

Turns out Paris is littered with railway stations. There were ten big “gares” or termini: the seven I’ve mentioned, along with the the Gare de Vincennes on the Place de la Bastille (demolished and replaced by the Opera Bastille), a terminus at Invalides (a building now occupied by Air France), and the original terminus of the Sceaux line at Denfert-Rochereau.

Add to that a sprinkling of intermediate stops (which the the book calls “stations” rather than “gares“) between the edge of the city and the termini. And finally, add all the stations on the Petite Ceinture around the edge of the city. All told, more than 50 in the heyday of railway travel.

Some have disappeared, some have been altered beyond recognition, and some have been put to other uses. Quite a few, such as the Port Royal station, shown below, have become RER stations. (This is the Réseau Express Régional – the regional express network that is part of the Paris Métro system.)

A couple of years ago, when we were staying nearby, I enjoyed using this old-fashioned station, which has hardly changed since it was built in 1895. The book describes it as being in the “pagoda style,” much in vogue at the time for little stations like this.

Port Royal was on a short railway line that went to Sceaux, a suburb less than 10 km to the south of Paris. Originally, this line, which dates from the 1840s, stopped farther south at Denfert-Rochereau (another station that is still standing), but it was extended farther north into the city in 1890s with this stop at Port Royal and an underground terminus at Luxembourg. Today, all three stations are part of the RER B line.

Here’s another pagoda-style station. This stop on the RER C line is now called Javel, but it was once the Gare du Pont Mirabeau (which sounds so much more romantic).

Not all of the stations are in the same whimsical style. Boulainvilliers, a squat, defensive-looking establishment built in 1899 in the 16th, looks as if the railway owners were expecting the place to be attacked.

On the same line, a little farther to the northeast, is the former Courcelles-Levallois Station, now the Pereire-Levallois station, still in service on a commuter rail line called Transilien. This is one of several stations characterized by large, round-topped entry doors. The modern inserts are not very graceful, but with the original panes of glass, these buildings looked a bit like garden pavilions or orangeries.

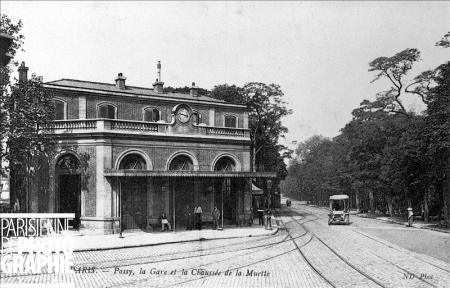

A similar style is evident at the Passy-La Muette station, now a restaurant in the 16th, not surprisingly named La Gare. It was once a stop on the line between the Gare St-Lazare and Auteuil. The building dates back to the 1850s.

This is how it looked when it was still in service.

On the other side of the city, in the 12th, is the former Gare de Reuilly, now an annex to the Mairie of the 12th arrondissement. This photo from the Roger-Viollet collection shows it in the late 19th century.

I went looking for it on Google and found it at 181 avenue Daumesnil, looking none the worse for wear, still bearing the blue sign identifying it as a station.

Reuilly was the last stop before the terminus, the Gare de Vincennes, on the Place de la Bastille. In between was a raised viaduct with huge brick arches.

I found two postcards of the vanished terminus in our collection. The first shows it in context, facing the Colonne de Juillet (it’s the large building just behind and to the right of the Colonne). This postcard is dated 1922, but the image is likely some years older than that.

The second shows a closer view; the postcard was sent in 1907. Across the top of the building is written “Chemin de Fer de Vincennes.” Arrivals on the right and far left, departures second on the left and up a staircase (Escalier du Départ), baggage and parcels in the middle.

What I find interesting is that this enormous building was the terminus of a line that was less than 50 km long, and ended in the small town of Verneuil l’Etang. It seems a great deal of infrastructure for a fairly minor route. (Similarly, the Sceaux line was very short, yet well endowed with prominent stations.)

The Opera Bastille, a gleaming modern building of glass and metal, now stands where the Gare de Vincennes once stood. Flowers and trees grow along the top of the viaduct, and chic boutiques and art studios occupy the spaces under the arches below, in a nice example of adaptive reuse known as the Viaduc des Arts.

On the whole, Paris has retained more than half of its more than 50 stations, most of them incorporated into the RER system, with a few put to other uses. It’s an enviable heritage.

Indeed, each time we arrive from the airport after hours spent in a cramped seat in a sealed capsule, followed by a long taxi ride in rush-hour traffic on the highway and Périphérique, I envy travellers who arrive in Paris by train. The Eurostar, the TGV, the Train Bleu, the Orient Express…now that is the stylish way to enter the city.

So how many railway stations does Paris have today? The book lists 24 historic stations still in use as SNCF (railway), RER, or Transilien (commuter) stations and 9 new stations added to the network (most of them underground), so the correct answer would be 33.

Text by Philippa Campsie; historic photographs from the Roger-Viollet collection, “Paris en images”; contemporary photographs from Google Street View or by Philippa Campsie.

*Pascal Lambérieux, Paris et ses 50 Gares (Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire: Alan Sutton, 2010).