On our first visit to Paris together, Norman took a picture of me standing beside a Wallace fountain. I liked the dark green caryatids and the elegant dome.

Later, on a visit to the Pavillon de l’Eau, we learned that these fountains were a gift to the City of Paris from an Englishman named Wallace. How jolly decent of him, we thought. And until recently, that was all we knew about the matter.

Then I read Matthew Harrison’s history of St. George’s Church in Paris, in which he summarized the odd life of Richard Wallace (1818-90), a benefactor of the church. Intrigued by his tale, I did more research and found a very complicated story indeed.

To start with, Wallace was not his name by birth, but one that he chose for himself. He was brought up in Paris by his grandmother, but he called her Aunt. He was the illegitimate son of an English nobleman who employed him as a secretary and left him a fortune, but never acknowledged him as a son. His French wife lived for years in England, but never learned to speak English, although she was the one who left the huge bequest of mostly French art to the English nation: it is now known as the Wallace Collection and is still on view in London.

Maybe I should start at the beginning.

Let’s go back to 1798, when Richard Wallace’s grandfather, Francis, son of the Marquess of Hertford, eloped with the illegitimate daughter of an Italian dancer. There is a lot of illegitimacy in this story. Her name was Maria Emily, but everyone called her Mie-Mie. Although she had been born out of wedlock, her wealthy father (the Duke of Queensberry) made sure that she grew up in comfort. Here is a picture of her, in a miniature from the Wallace Collection.

Mie-Mie was wealthy, but because of her origins, she was not accepted into London society after her marriage. She convinced her husband to move to Paris with their two children (a girl and a boy). This was 1802, during a short truce in the war between England and France. Mie-Mie loved Paris and settled in happily, but her husband frequently went back to England without her.

Soon, relations between England and France were fraying, and so were those between Francis and Mie-Mie. Francis returned to England, but Mie-Mie stayed in Paris, now with three children (one was, ahem, not her husband’s). When her father the Duke of Queensberry died, he left her a comfortable inheritance, and she no longer needed her husband’s support.

Her first son Richard (who had been born in 1800) grew up in France and went to England after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815. He joined the British army as a hussar. In 1822, his father Francis succeeded to the family title and became the third Marquess of Hertford. Mie-Mie was now a Marchioness.

Two years later, Richard turned up on his mother’s doorstep with a six-year-old boy called Richard Jackson. This was his illegitimate son, who had been given his father’s Christian name and his mother’s surname. (Well, it wasn’t really her name, it was the name she had taken after separating from her husband – I told you this was complicated – but close enough.)

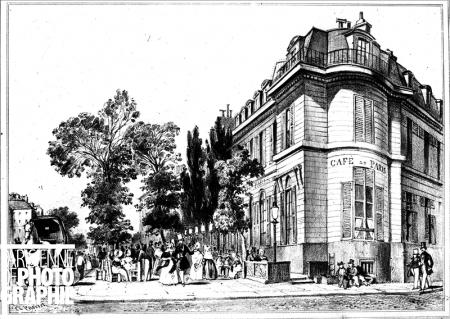

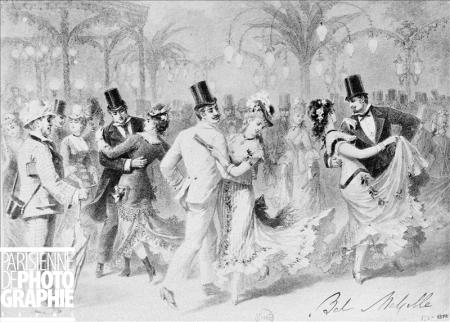

Mie-Mie took the little boy in and told him to call her “Tante.” Her beloved daughter had died a few years earlier and Richard Jackson seemed to fill a hole in her life. She moved to the rue Taitbout and took an apartment directly over the Café de Paris, one of the smartest restaurants in the city. Richard Jackson grew up watching the comings and goings of le haute monde underneath his windows. He also watched the comings and goings of Mie-Mie’s younger son Henry, a founder of the Jockey Club and well-known man about town.

Meanwhile, his father Richard wandered around Europe, at one point stopping in Paris long enough to acquire a mistress and a little chateau in the Bois de Boulogne called Bagatelle. Eventually, he settled in Paris in an apartment on the rue Laffitte, installed his mistress nearby, and started to collect art.

His first purchase was a Fragonard, which he bought at a public auction. At the time, nobody was interested in 18th-century French art. It had gone out of favour during the Revolution and in the 1840s, you could pick up Fragonards, Watteaus, and Bouchers for a song.

In 1842, Mie-Mie’s husband Francis died, and her son Richard became the fourth Marquess of Hertford. Having inherited the family fortune and estates, he could now collect art on a grand scale, and he did.

That same year, at the age of 24, Richard Jackson formally changed his name to Richard Wallace, his mother’s maiden name. By now, he had a mistress of his own, and even a son by his mistress (the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree), but he still lived with Mie-Mie, leading a bohemian life and frequently running into debt. The new Marquess decided that his son needed an occupation, so he made Richard Wallace his personal secretary. But he never acknowledged that his secretary was his own son.

The two worked together closely. Richard frequently acted as the Marquess’s agent in art purchases, and kept records of the ever-expanding collection, which contained Dutch, Italian and Spanish masters as well as French, and furniture as well as pictures.

When the Revolution of 1848 broke out, the family (minus Richard Wallace’s mistress and child) beat a hasty retreat. They spent six years in Boulogne before returning to Paris. Mie-Mie, Henry and Richard settled back into the rue Taitbout, while Richard Wallace’s mistress lived elsewhere, looking after their son, who was now in his teens.

Mie-Mie died in 1856, deeply mourned by her sons and grandson. Her younger son Henry died two years later (his will listed four children by various mothers – typical). Her remaining son, the Marquess, who never married, settled at Bagatelle and became increasingly reclusive while continuing to amass artworks.

Fast forward to 1870, when everything changed. As the French engaged in a disastrous war with the Germans, the Marquess was dying at Bagatelle. After his death and burial at Père Lachaise, the family estates passed to a cousin, who became the new Marquess, but the art collection, several properties (including Bagatelle), and a huge sum of money went to Richard Wallace.

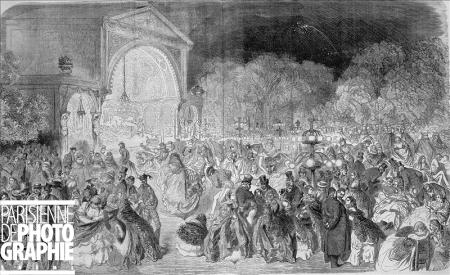

Wallace had little time to enjoy his new wealth. Paris was in chaos. The French army was defeated, the Emperor Napoleon III was captured, and the Empress Eugénie fled to England. Wallace moved the collection from Bagatelle into his father’s old apartment on the rue Laffitte to keep it safe (he himself still lived in Mie-Mie’s former apartment). It was the right decision, as the lovely Bagatelle was later commandeered by the military.

Wallace never thought of leaving Paris, but he helped other English residents escape. He started a relief fund to help feed the poor, who were starving in the besieged city, and to help people left homeless by shelling. He also set up a medical clinic to treat the wounded. At some point, he even found time to marry his long-suffering mistress, Julie Castelnau, 30 years after the birth of their son.

Wallace also remained in Paris during the Commune that followed the war, horrified by the bloodshed it caused, but willing to help those in need. When it was over, the French made him a member of the Legion of Honour and named a street after him, and Queen Victoria made him a baronet in recognition of his services to the English in Paris.

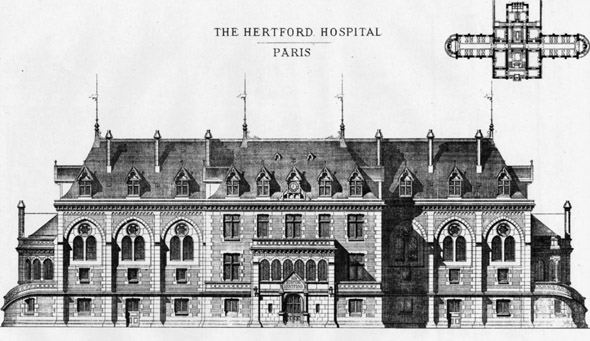

The violence of the Commune had so shocked Wallace that he decided to move to London in 1872, taking most of the collection with him. His parting gift to the city where he had lived was the 50 fountains that Parisians call les Wallaces, designed by the sculptor Charles Auguste Lebourg. (Later, Wallace honoured the memory of his father by founding and endowing the Hertford British Hospital in Paris, which opened in 1879.)

In London, Wallace moved in the best circles, dining with the Prince of Wales and the Prime Minister, but his wife Julie never learned to speak English and did not go out much. Their son, Edmond, disliked England and returned to France frequently. You won’t be surprised to learn that he had four children with a woman he did not marry. Wallace was furious and said, “Mon Dieu, est-ce que nous n’aurons jamais fini de bâtards?” (Are we never to have an end to bastards in this family?). Although Wallace became estranged from his son, he was devastated when Edmond died in 1877.

After this blow, Wallace withdrew from society, and went back to Paris to live at Bagatelle, leaving Julie in their huge London house with its enormous art collection. He died in 1890 in the same bed and in the same room as his father, attended only by a few servants, and was buried with his father at Père Lachaise.

His will left everything he owned to his wife. It was she who left it to the British nation in her will. She remained in England to the end of her life, taking a translator with her whenever she went out. She died in 1897 and was buried with her husband in Paris.

Edmond’s descendants are still living in France, the Bagatelle still stands in the Bois de Boulogne surrounded by its gardens, and the Wallace Collection remains a fixture in London. The Café de Paris, which stood at the intersection of the rue Taitbout and the boulevard des Italiens, closed in 1856, the year that Mie-Mie died (there is another restaurant there now, and a Monoprix). But the Wallace fountains continue to adorn the streets of Paris, the enduring legacy of an unconventional family.

Text by Philippa Campsie, original photographs by Norman Ball, portraits from the Wallace Collection website, picture of Cafe de Paris from Paris en Images, photograph of Bagatelle and Hertford-Wallace family tomb from Wikimedia Commons; photograph of the Hertford Hospital from Archiseek.

Sources:

An Anglican Adventure: The History of Saint George’s Anglican Church, Paris, by Matthew Harrison, 2005, published by Saint George’s Anglican Church, Paris

The Greatest Collector: Lord Hertford and the Founding of the Wallace Collection, by Donald Mallett, 1979, Macmillan.