This blog is dedicated to the memory of my father, John Campsie, 9 April 1921 – 8 February 2014. He passed his love of travel on to me and encouraged me to learn French.

The first time I saw Paris, it was a mistake. We were actually supposed to be in Greece, not Paris. And it was all my fault.

I was eight years old. At the time, my family was living in North Berwick, Scotland, because my father had taken a year-long sabbatical from his publishing job in Toronto to write a book. During the Easter holidays that year, he planned to take us first to Malta, his birthplace, and then to Greece.

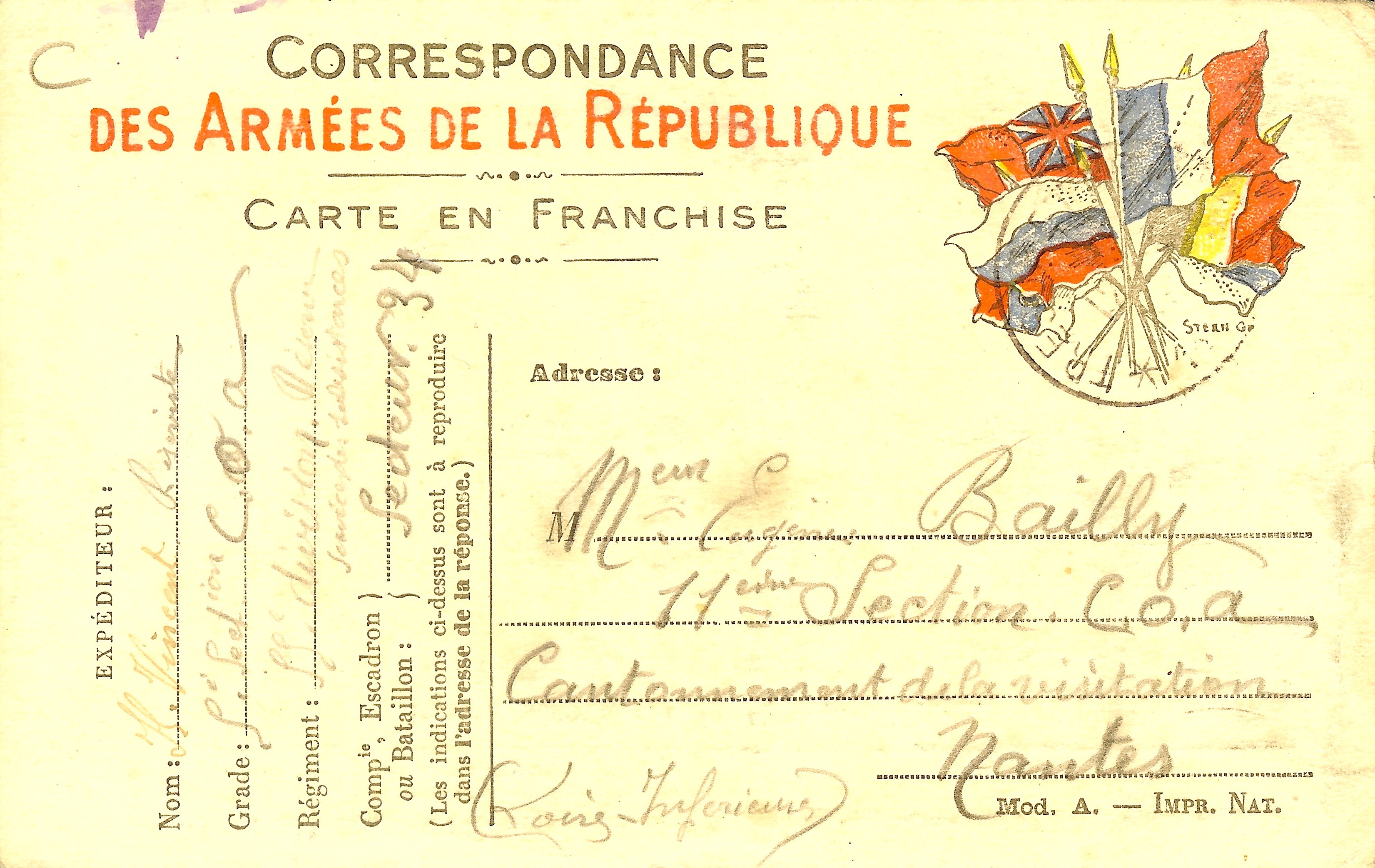

At first, our holiday went pretty much according to plan. We flew to Malta, and spent one night in a hotel that my father remembered from his childhood in Valletta in the 1920s. Time had not been kind to the hotel – everything seemed mouldy and damp and the waiters in the dining room were elderly and hard of hearing. The next day we moved to a modern hotel.

On Sunday, we went to a service at St. Andrew’s Scots Church in Valletta. In the 1920s, my grandfather had been the minister at this church, as well as a chaplain to the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet stationed in Malta. That is how my father had come to be born there – in the manse beside the church on Old Bakery Street.

The photo shows my mother, my sister Alison, and me dressed in our Sunday best outside the church. The house just beyond the stone church, with the knobs on the top, is the one where my father was born.

During the service, I started to feel queasy, and then very sick indeed. My mother took me outside and we wandered about in the sunshine for a while, until the service was over. I spent the rest of the day in bed. The following day, I was still very sick, and my parents got a doctor, who discovered that I had a perforated eardrum. He prescribed antibiotics and told us, “She cannot fly in an aeroplane for at least three months.”

So we had to scrap the plan to go to Greece. Instead, my father had to figure out a way of getting from Malta back to Scotland by land and sea. This must have been enormously stressful for him, but I didn’t know that at the time. When you are eight years old, you assume your parents will solve all problems. And he did.

I recovered enough to see something of the island – I have my father’s 35 mm slides showing trips here and there in a rented Morris Minor convertible. But I had to wear one of my mother’s scarves to keep the wind out of my ear.

Eventually, we set out on our epic journey home. First, we had to take a djasa (one of the colourful local rowboats) out to a steamer that would take us to Sicily. This is the photograph my father took while we were crossing Valletta harbour with our luggage.

The crossing was choppy. We landed in Syracuse, where we spent the night. Octopus was on the menu of the restaurant where we ate, something none of us had ever tried before. I understand that there is a way to prepare octopus that makes the experience of eating it less like chewing boiled rubber bands, but the chef in Syracuse did not use that technique.

The next day, we took a train to Messina, ferry to Reggio, and another train to Rome, where we stopped for a couple of days. My father’s pictures show us in the Forum and the Boboli Gardens and touring the Vatican. Here Alison and I are standing on the entrance gate to the Palatine Hill, with the Colosseum in the background.

Looking back, I am astonished that we found a hotel room, because it was Holy Week and people were pouring into Rome. But my father seems to have solved that problem somehow. The name “Hotel Lux” sticks in my mind. The hotel is still there, near the train station. It may well have been where we stayed.

Here is a rare picture of my father in Rome. Rare, because he was usually behind the camera, not in front.

We left Rome on Easter Day itself, on an almost-empty train to Turin. That in itself is remarkable. Who do you know leaves Rome on Easter Day?

From Turin, we went to Torre Pellice for a few days. This was another place my father had known as a child: in the 1920s, he and his family had spent several annual vacations in a nearby village called Angrogna.

I gather his family holidays consisted largely of taking long walks and admiring mountain scenery. So that is what we did, too. I have pictures of us hiking along mountain trails and eating picnics beside streams. Here we are in the Italian Alps; I am looking enviously at my sister’s camera. My father seems very formally dressed – perhaps it was a Sunday.

I don’t know what Angrogna is like now, but back then, it didn’t seem to have changed much since the 1920s. My father happily recognized his family’s old haunts. Indeed, the photo below, which he took on that trip, resembles a watercolour my grandmother painted several decades earlier, with the addition of a few cars. And the three of us. (What do you suppose had caught our attention on the left?)

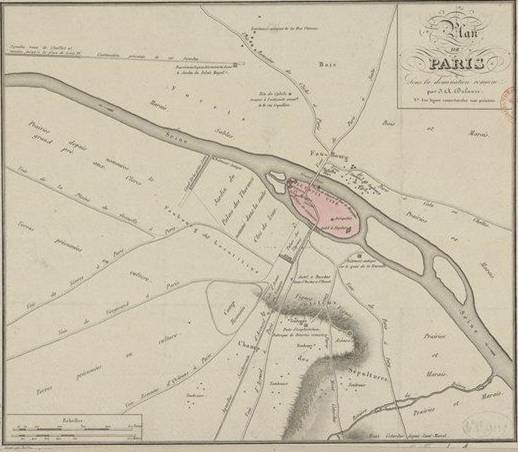

After a few days of mountain walking, we set off again, by train from Turin to Paris. I suppose we would have arrived at the Gare de Lyon. That must have been my first view of the city.

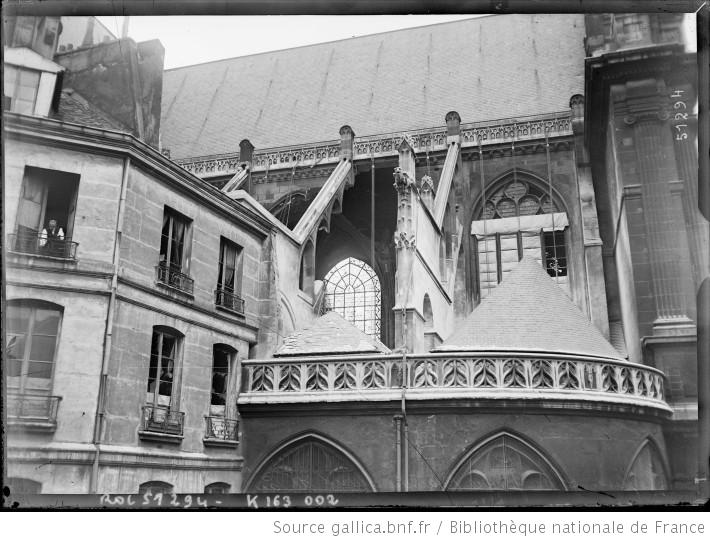

Where did we stay? My memory is that the hotel was not very big, on a narrow street opening into the Place de la Madeleine. The only street that fits that description is the Passage de la Madeleine, on which is located the Hotel Lido at number 4. It was well-established at the time and apparently quite cheap. So that might have been the place. Or not; memory does play tricks.

What did we do? Here my memories are overladen by those from subsequent trips and, alas, my father took only a couple of photographs. But there is one of us walking by the Seine and another of Alison and me pushing around a toy sailboat on the pond in the Jardin du Luxembourg. I do remember that.

After a few days, we moved on. Train to Calais, ferry to Dover, train to London, train to Edinburgh, train to North Berwick, journey’s end.

So that is how I first saw Paris. We went back as a family when I was a teenager, and there were two memorable school trips before I returned to study at the Sorbonne. In 1983, my father and I found ourselves in Paris – once again by mistake. We were supposed to be in Russia. This time, it wasn’t my fault. But that is another story altogether.