The huge Maison de la RATP on the quai de la Rapée has a sweeping view of the Seine and an impressive central atrium in which are positioned a few examples of historic trams and omnibuses. What it does not have, surprisingly, is a proper museum or even a small gift shop.

Norman and I wandered in on a summer’s day earlier this year. We’d seen the building from across the river as we were lunching on the roof of the Cité du Design et de la Mode, and we were curious about the interior. We asked about the non-existent museum and shop at the reception desk and were directed to the tiny hard-to-find gift shop in the bowels of Les Halles (shown below; now closed). The receptionist was sympathetic. She’d seen the same disappointment in tourists’ faces before.

We also went in search of toilettes. The building had several, but they were accessible only to those who knew the digicode. Eventually a woman at a desk in a side area where conferences and seminars were being held took pity on us and allowed us to use the ones there.

Before we left the building, we took some pictures. But the experience was unsatisfying. For a city with such a rich array of specialized museums (such as the one we mentioned in the last blog), the lack of a transport museum is distinctly odd.

Later, in a book called Metro Insolite by Clive Lamming, I found an interesting comment in a photo caption. Below a picture of the lush foliage in the modern Gare de Lyon station, I read: “Ambiance tropicale à la station Gare de Lyon ; cet espace était destiné à accueillir un accès au musée des Transports, hélas non réalisé.” [Tropical ambiance in the Gare de Lyon station; this space was intended to house the access to the Museum of Transport, alas, never realized.] That was all. Clive had nothing further to say on the subject beyond that telling “hélas.” So I went looking for clues.

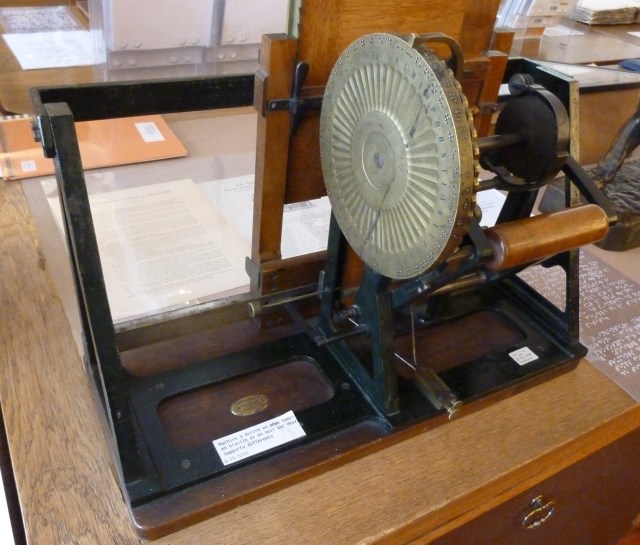

In fact, there is (or was) a museum, outside Paris, operated by the Association pour le Musée des Transports Urbains, Interurbains, et Ruraux (AMTUIR), showcasing rolling stock from cities throughout France, including Paris. It was created in 1957 at the time that most French cities were tearing out tramlines and tossing out tramcars (which are now being carefully put back in many cities, at considerable expense).

The Association, composed mainly of enthusiastic amateurs and some retired transport employees, saved what trams it could, and put them on display, first in a former tram depot in Malakoff, and then, in 1972, in an old bus depot in Saint-Mandé. Later it added omnibuses, trains, and other rolling stock from various European cities. The photo below is of the Saint-Mandé museum.

(You can also see some 1970 pictures of the Malakoff museum at this Flickr site. The depot sheds are still there in Malakoff, near the intersection of boulevard Gabriel Péri and avenue du 12 février 1934, but have been put to new uses.)

(You can also see some 1970 pictures of the Malakoff museum at this Flickr site. The depot sheds are still there in Malakoff, near the intersection of boulevard Gabriel Péri and avenue du 12 février 1934, but have been put to new uses.)

RATP has had a cordial relationship with the Association, offering spaces in its unused depots for the collection, and lending out old vehicles for display. But in 1998, when the new RATP headquarters was built on the quai de la Rapée, the Saint-Mandé depot was sold. The Association, with the help of the RATP, went looking for a new home. A former airplane factory in Colombes seemed suitable, the RATP bought part of the site, and the collection was moved there in 2001. Studies were done on how to fix up the place to make it into a proper museum.

Then, following a municipal election in 2002, the administration of Colombes changed. The incoming mayor and councillors declared themselves adamantly (and inexplicably) opposed to hosting the museum. Planning came to an abrupt halt. Stalemate. Several years passed.

In 2006, another suburban municipality, Chelles, expressed interest in hosting the museum and an agreement was reached. AMTUIR moved some of its vehicles there. But the space was much smaller, and could not accommodate the 170 or so trams, buses, and trains AMTUIR had collected. The remainder were put in storage in a northern Paris suburb. Since then, the project seems to have stalled, and it appears that the museum has never officially opened.

All of which, you will have noticed, has nothing whatsoever to do with the Gare de Lyon near the Maison de la RATP. What was planned for that site? After all, the AMTUIR museum seems to have been a museum of rolling stock, but a Museum of Transport, like the ever-popular one in London’s Covent Garden, can tell a much wider story – about the stations, the routes, the design, the passengers, the people who worked for the company. Transport is not just about vehicles; it’s also about people and their stories.

The question, and the comparison with London, got me thinking. The Paris Métro and its associated buses and trams are very different from their London counterparts. The London Underground is much older (the first line opened in 1863). It has a strong visual identity, from red double-deckers to the circle-and-bar logo to the widely imitated map by Harry Beck. It has its emotional wartime history, when it provided shelter to so many people during the Blitz. It has a legacy of attractive and often witty advertising posters. Its lines have memorable names, and are consistently associated with certain colours (Bakerloo is always brown, Picadilly is always blue).

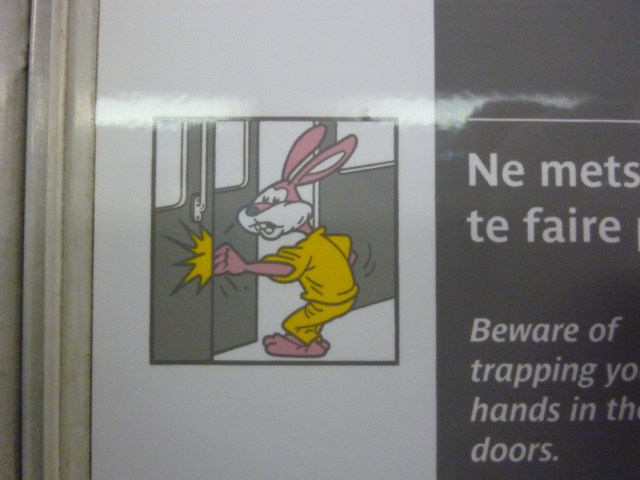

Now think about the Paris Metro. Built in 1900, it was a relative latecomer in municipal railway-based transit compared with London and New York. Its visual identity is idiosyncratic and incoherent – from writhing Hector Guimard entrances to modern signs (a yellow M in a circle) to the current, quite lovely RATP logo to one-off signs like the one shown above. Its stations range from our favourite, the imaginative Arts-et-Metiers station that evokes Jules Verne, to old-fashioned open-air platforms (shown below) to bleakly functional underground stops to unsuccessful makeovers, like the one at Franklin Roosevelt on the No. 1 line, which reminds me of the interior of a 1980s disco.

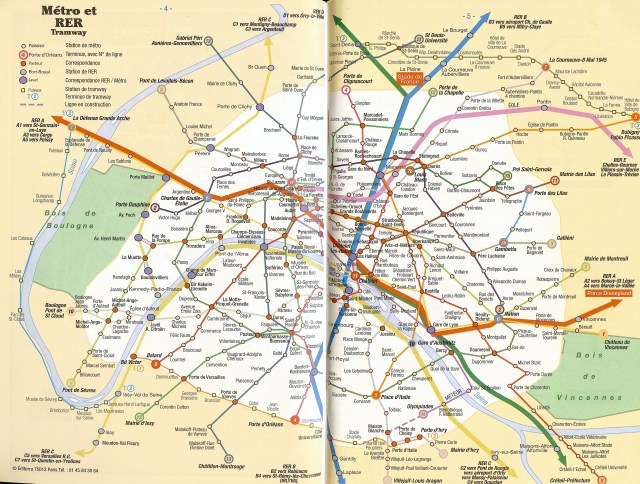

The buses today are unremarkable, now that the green ones with the open-air platforms at the back are gone (ah, fond memories!). There are many versions of the map, using a variety of designs and colours (the one below is from our copy of Paris Arrondissements, and the colours of the various lines do not necessarily correspond to those you will find on official maps). The Métro did provide shelter in a few stations on a few occasions during the war, but Paris did not suffer through a Blitz. It has few advertising posters and those are unmemorable.

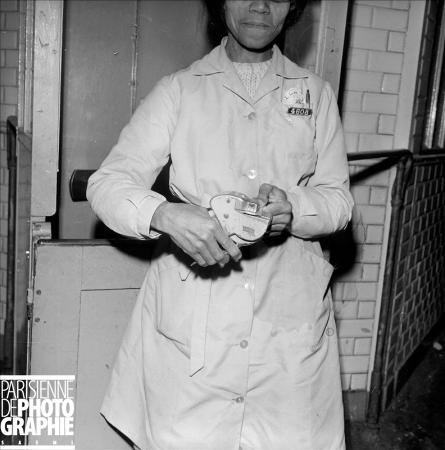

All of which is not to say that the RATP doesn’t deserve a museum. It may have lost control of its visual identity, but it is still an institution with a long and distinctive history. You have only to look at a book published in 2011 called Les archives inédites de la RATP, 1850–1950 [The Unpublished Archives of the RATP, 1850–1950] by François Siegel. This huge coffee-table tome is filled with never-before-seen photographs of everything from the other flood (did you know there was one in 1924 as well as the big one in 1910?) to the camps created for Les Enfants du Métro (the children of Métro employees) to the lonely plight of the poinçonneurs and poinçonneuses (the men and women who once sat in station booths to punch passengers’ tickets).

A whole social history is there. Paired with some of the actual artefacts, it would make for a riveting museum. One day.

A whole social history is there. Paired with some of the actual artefacts, it would make for a riveting museum. One day.

And think of the merchandising opportunities in a proper shop! Metro maps on everything from mousepads to mugs, not to mention model trains, Hector-Guimard-style trinkets, and perhaps even a series of children’s books about the further adventures of the familiar pink rabbit in yellow pyjamas – le Lapin du Métro.

But for now, the RATP is not very welcoming. According to the RATP website, its archives are open to the public – by appointment only. You can’t just wander in.

The website also notes: “Since 1992, RATP has embarked upon a vast process of restoring its historic rolling stock. When a series of rolling stock is discontinued, one example is taken away to be preserved for future generations. A number of vehicles and objects from this collection are exhibited permanently in the reception hall of the Maison de la RATP (RATP’s headquarters near Gare de Lyon). The others are preserved and stored, with a view to being exhibited at the new Musée national des transports urbains.”

One day. One day.

Text by Philippa Campsie; original photographs by Philippa Campsie and Norman Ball. Image of poinçonneuse from Paris en Images. Image of museum at Saint-Mandé from Direction générale des patrimoines de France.

Text by Philippa Campsie; original photographs by Philippa Campsie and Norman Ball. Image of poinçonneuse from Paris en Images. Image of museum at Saint-Mandé from Direction générale des patrimoines de France.