It seems that humans cannot resist dabbling in predicting the future. We have an innate need to ignore Yogi Berra’s clear warning, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” So what did the year 2000 look like from a vantage point 100 years earlier? Let’s look at a few examples from a series of cigarette cards designed to be given away at the International Exposition of 1900 in Paris.

Our parlour maid has a wonderful-looking machine to clean her wooden parquet floor. The machine looks a bit awkward, but has a traditional scrub brush and bar of soap. Indeed, it seems to be electrically powered, but the cord leads only to the wand the maid is holding.

Our parlour maid has a wonderful-looking machine to clean her wooden parquet floor. The machine looks a bit awkward, but has a traditional scrub brush and bar of soap. Indeed, it seems to be electrically powered, but the cord leads only to the wand the maid is holding.

As for the rest of the room, it seems very much of the late 1800s: a large potted plant; the ever-respectable but economical upright piano; heavy curtains and a blind at the window; a statue on a plinth; and two paintings on the walls. Did year 2000 ever look more like the year 1900? At least the maid does not seem to have a strenuous job. Let’s look at some other workers.

Clearly our farmer of the year 2000 is living better electrically. He sits on a stool working the controls while the electrically powered machines do what was once done by human labour. An electric harvester cuts the grain and perhaps even ties it in stooks. Another machine piles hay or grain into large mounds.

Clearly our farmer of the year 2000 is living better electrically. He sits on a stool working the controls while the electrically powered machines do what was once done by human labour. An electric harvester cuts the grain and perhaps even ties it in stooks. Another machine piles hay or grain into large mounds.

Rapid everyday delivery by postmen who had conquered the air meant one no longer had to depend on those unreliable telegraph delivery boys. All has been arranged. Just lean out from your balcony and grab the letters as he flies by.

Rapid everyday delivery by postmen who had conquered the air meant one no longer had to depend on those unreliable telegraph delivery boys. All has been arranged. Just lean out from your balcony and grab the letters as he flies by.

After a hard day’s work, or just to get ready for a night out on the town, a gentleman would need to visit his barber. But in the year 2000, the barber was a machine controller. Mechanical arms shave the man sitting in the chair on the right. He looks a bit uncomfortable. The customer standing seems finished and the final errant hairs on his coat are being brushed off mechanically. The jolly man in the chair on the left is enjoying a chance to relax. Perhaps he is thinking of a trip to his tailor for a made-in-no-time suit for the opera.

The man’s measurements are taken mechanically and sent to the forbidding-looking tailoring machine. It begins by gobbling up material from the bolt of fabric to the left of the machine. After internal machinations, it spits out a completed suit jacket. But the men’s costumes show that fashion has not changed a bit since 1900.

The man’s measurements are taken mechanically and sent to the forbidding-looking tailoring machine. It begins by gobbling up material from the bolt of fabric to the left of the machine. After internal machinations, it spits out a completed suit jacket. But the men’s costumes show that fashion has not changed a bit since 1900.

Meanwhile, at home, other preparations are taking place.

Again we see the electric wires, control handles, and, above the bathtub, a brush with a strong resemblance to that used by the parlour maid to scrub the parquet floors. Madame is seated comfortably, even seductively, while her hair is done to perfection by electrical apparatus and all manner of other preparations completed. The mirror obscures what is happening to her foot, but the contraption looks fierce.

Again we see the electric wires, control handles, and, above the bathtub, a brush with a strong resemblance to that used by the parlour maid to scrub the parquet floors. Madame is seated comfortably, even seductively, while her hair is done to perfection by electrical apparatus and all manner of other preparations completed. The mirror obscures what is happening to her foot, but the contraption looks fierce.

Our happy couple of the future live only a short walk away from the Aero-Cab Station, where one never has to wait long for an aero-cab. The trip is over so quickly that there is hardly time to glance at the newspaper purchased at the newsstand before taking the elevator to the boarding level.

Our happy couple of the future live only a short walk away from the Aero-Cab Station, where one never has to wait long for an aero-cab. The trip is over so quickly that there is hardly time to glance at the newspaper purchased at the newsstand before taking the elevator to the boarding level.

The couple look down from their box at the Opera. Members of the audience are dressed in their finest, the story unfolding on stage is an old one. The music emanating from the orchestra pit comes from familiar instruments, all of which are controlled mechanically. The conductor has been reduced to sitting at a control panel. And without musicians to watch, something seems to be missing from the drama of a night at the opera.

The couple look down from their box at the Opera. Members of the audience are dressed in their finest, the story unfolding on stage is an old one. The music emanating from the orchestra pit comes from familiar instruments, all of which are controlled mechanically. The conductor has been reduced to sitting at a control panel. And without musicians to watch, something seems to be missing from the drama of a night at the opera.

But the next day brings an outing in a highly unusual vehicle.

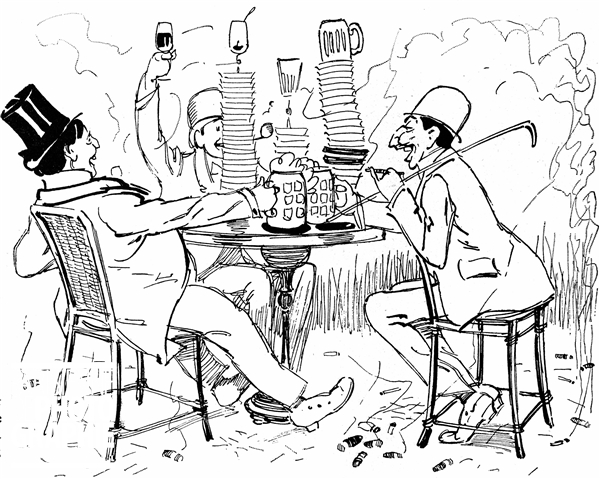

Who would have thought that one could put a house on wheels, fit it up with a steam engine, chefs, waiters, and a skilful driver? All of this so one could dine in comfort while heading for an afternoon at the seashore. Such a delightful prospect, part of what makes the future worth waiting for.

Who would have thought that one could put a house on wheels, fit it up with a steam engine, chefs, waiters, and a skilful driver? All of this so one could dine in comfort while heading for an afternoon at the seashore. Such a delightful prospect, part of what makes the future worth waiting for.

For the adventurous sort, there was always (sea)horseback riding. But with the boots, breeches, swords, and breathing apparatus, it all seems too energetic. The new underwater breathing apparatus was best reserved for more decorous pursuits.

For the adventurous sort, there was always (sea)horseback riding. But with the boots, breeches, swords, and breathing apparatus, it all seems too energetic. The new underwater breathing apparatus was best reserved for more decorous pursuits.

A jolly good game of croquet made for a perfect day. And as the woman’s dress suggests, it was an entertainment for those who knew how to dress. But some who enjoyed an afternoon watching a race beneath the waves seemed to have taken some liberties with their attire.

A jolly good game of croquet made for a perfect day. And as the woman’s dress suggests, it was an entertainment for those who knew how to dress. But some who enjoyed an afternoon watching a race beneath the waves seemed to have taken some liberties with their attire.

Clearly the woman with the scandalously short skirt must have come directly from her work dancing on stage in a club frequented by the…well, by those whose names and stations in society we shall not repeat here.

Clearly the woman with the scandalously short skirt must have come directly from her work dancing on stage in a club frequented by the…well, by those whose names and stations in society we shall not repeat here.

But much as the world beneath the sea beckoned, there were other opportunities to have fun, high above the mountains.

These naughty lads have been lucky to escape with their lives when the mother eagle attacks them to protect her baby eaglets. Have little boys not learned anything in the last 100 years? Whatever are they teaching them in the schools?

These naughty lads have been lucky to escape with their lives when the mother eagle attacks them to protect her baby eaglets. Have little boys not learned anything in the last 100 years? Whatever are they teaching them in the schools?

The new learning machines were perhaps not as effective as they were expensive. The teacher could feed the books into the machine; the least well-behaved boy in the class could turn the crank, but what did the electric wires feed into the young pupils heads? Today we know the expression “garbage in, garbage out.” Perhaps the books were outdated and stale. And how did anyone know if the boys (no girls to be seen in this school) were even paying attention to the lessons coursing through the wires?

Were the lads dreaming of the day when they would have their own airplane? Or a career as a dashing aviation policeman?

Or were they imagining a career in surveillance?

Or were they imagining a career in surveillance?

Perhaps some dreamed of the day when young boys (note the sailor suits in the image below) went off to war. Some by air…

And perhaps some dreamed that they could rescue those in peril.

And perhaps some dreamed that they could rescue those in peril.

And as each dreamed of the future, how many would realize what a jumbled mixture of past and present their dreams were made of? While hovering in the air to rescue child and infant, a steam engine on the ground pushed water up through the hose and onto the flames.

And as each dreamed of the future, how many would realize what a jumbled mixture of past and present their dreams were made of? While hovering in the air to rescue child and infant, a steam engine on the ground pushed water up through the hose and onto the flames.

The images presented here show colourful visions of the year 2000 when it was 100 years into the future. There are 87 or more known cards in the series started by the French artist Jean-Marc Côté. The artist had been commissioned by a toy-and-novelty company called Armand Gervais et Cie of Lyon to produce images for cigarette cards to be distributed at the International Exposition of 1900 in Paris.

Unfortunately, Gervais died unexpectedly and his company ceased operations. The cards were never distributed. The plant closed down and was left untouched for almost a quarter of a century. Then a toy collector, Monsieur Renaud, visited the premises with the idea of using it to manufacture toys. He discovered instead the untouched inventory of the Gervais company, including the cards. Monsieur Renaud decided not to produce toys, but to buy the entire stock of the company as the basis of a left-bank store called Editions Renaud.

In 1978 the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov and his wife were living in Paris. They visited Editions Renaud, hit it off with Monsieur Renaud (who was then quite elderly) and bought a set of cards. According to Asimov, the set was the only one not to have been damaged by water in the abandoned factory. Intrigued with the collection, he wrote a book about it, published in 1986.

Futuredays: A Nineteenth-Century Vision of the Year 2000 is an astounding piece of work. I recommend it highly. I bought it some years ago, read it with enjoyment, and then somehow forgot about it until I was sorting some books that I had left in storage and rediscovered an old friend. Soon I, too, wanted to learn more.

My discovery of the online images of the Public Domain Review led to this blog. The site is well worth any time one spends there. So I dedicate this blog to Jean-Marc Côté, other unnamed artists who contributed to the series, Armand Gervais, Monsieur Renaud, Isaac Asimov and his wife Mariea (who, like my wife, speaks far better French than her husband).

Let us leave this blog with another improbable image. It reminds me of the many futuristic images and stories that entertained us in our younger years when we were enraptured by Popular Mechanics magazine and the works of Jules Verne. However entranced we may be by the new and different, we seem to seek comfort in novelty and unintentionally lug the past into our visions of the future.

Text by Norman Ball; images courtesy Public Domain Review