A few weeks ago, Norman embarked on some long-deferred tidying up and came across a beautiful bronze disc about 12 cm in diameter (not quite 5 inches across). He said he’d had it for years, and had probably bought it from a friend who was an antiques dealer in London, Ontario.

I knew exactly what it was. My grandmother had one too, but with her brother’s name on it. These bronze memorial plaques were sent to the families of men and women of Great Britain and its Empire who had died in the First World War. But I don’t think I’d ever looked at one quite so closely as I was able to look at this one.

I hadn’t realized that there are no fewer than three lions visible – the big one, another that forms part of Britannia’s headdress, and a third underneath the feet of the big lion – at first, I couldn’t figure out what that one was doing, but according to a description of the plaque, he is getting the better of the German eagle. I also spotted a lyre-shaped decoration on the trident and two dolphins (to represent Britain’s sea power).

More than 1.3 million plaques like this were issued after the war. This one was made at Woolwich Arsenal (others were made in Acton). Some people referred to the plaque as the Dead Man’s Penny, although hundreds were also made for women who served.

My first stop was the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to look up the name. Private Archie Joseph Bury Palliser of the 23rd battalion, Royal Fusiliers, died on 19 December 1915, aged 39. He is buried in Cambrin Churchyard Extension.

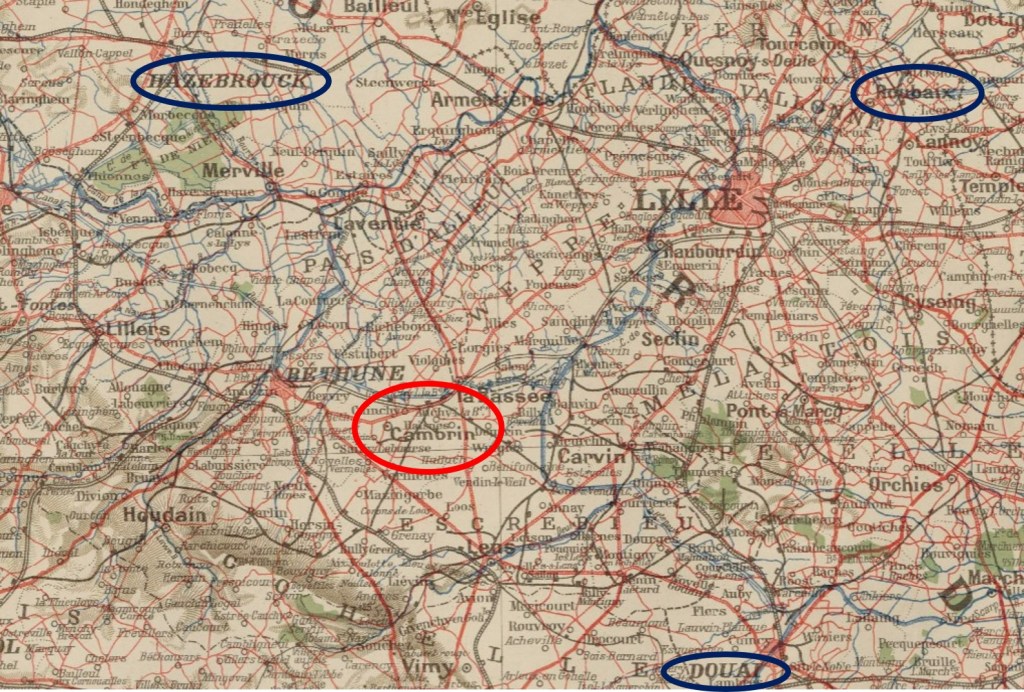

Cambrin is southwest of the city of Lille, north of Vimy Ridge. The map here contains names familiar from other blog explorations, such as Hazebrouck and Roubaix and Douai. It’s more than 50 kilometres north of Colincamps, where my great-uncle is buried.

Army records list Palliser as “Killed in Action,” but which action? I found the war diary for the 23rd Battalion for December 1915. The men had marched from Bethune on the 17th, with a piper at the head of the procession, in cold, wet weather. They were billeted for a day or so in a girls’ school at Beuvry. On the 19th the weather was dull but dry, and the battalion marched to a rendezvous at the Cambrin support point (about 5 km away) and then moved into the trenches.

There is a lot in the diary about troop movements, and even a special raiding party of 30 men, but nothing about fatalities, although on the following day the diary mentions a grenadier having been killed by a sniper. There are also mentions of intermittent shelling. Perhaps Palliser was in the raiding party and did not return. Perhaps he was killed by a shell or a sniper. A regimental history mentions that German snipers were “particularly troublesome” in that area.

But really, we don’t know how he died. So many young men died in obscure circumstances in the First World War.

So what do we know about his life?

I learned that Archie was born in London, England, on Christmas Eve 1874. This means that when he died, he was actually just a few days short of his 41st birthday, not 39 as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission had estimated. His father, Joseph Marryat Palliser (1843–98), was a wine merchant. I found a picture of Joseph online.

Archie was the youngest child in the family. He had four older sisters (Mabel, Norah, Ethel, and Fanny). A brother, Hugh, had died at the age of 11 in 1879. The family lived for many years in Baker Street with three servants. After leaving school, Archie worked for the Orient Line as a ship’s purser, travelling back and forth to Australia many times on ships transporting immigrants.

In the 1911 census of England, he is living with his widowed mother in Chichester Street, still listed as a purser. Then I took a look at the record for his mother, who is described as a “professor of dancing.” She was 72. I was impressed. Her full name was Sophia Louisa Isabel Hervé Bizet Michau (1838–1920). She used the name Isabel Bizet Michau in her advertisements.

I wish I had a picture of her. Isabel came from a family of dance teachers. I found her parents’ 1838 wedding certificate. Her father’s name is given as “Augustus Joseph Hervé Bizet, otherwise Michau,” and both he and his father, Louis Michau, are described as professors of dancing. It can’t have been a very secure profession, because Augustus declared bankruptcy in 1863, according to an announcement in the London Gazette.

Nevertheless, the Michau name was well known in England among those for whom dancing was an essential social skill. Augustus’s father, Louis Michau, was the nephew of the celebrated Madame Michau (c1783–1859), who

played a vital role as maîtresse de ceremonies for the Prince Regent’s court balls and dances in the early nineteenth century, and was later widely acknowledged as the undisputed expert on royal and aristocratic deportment. Moving between family houses in London and Brighton, following the seasons of fashionable Society, by the 1840s, Mme Michau and her family had built a reputation and clientele that was admired and envied by many within the pedagogic profession. As her most successful professional heir, Louis the elder had no need to re-locate each season to find pupils. To their house “every great family in the country sent its women and most of its men.”*

Madame Michau (born Sophie d’Egville) is given credit for introducing a form of the tarantella into England. Given the dance’s wild origins (an Italian dance ostensibly intended to dissipate the effects of a tarantula bite), the transition to polite society dancing suggests considerable talent. She even wrote music for her students to dance to.

But we are wandering away from Palliser and the First World War. How did the plaque with Palliser’s name on it get to Canada? That, too, turned up an interesting story.

I began looking into the lives of his four sisters. The oldest, Mabel, died unmarried in 1896 in London. In the 1901 census, the other three daughters – Norah, Ethel, and Fanny, who is now known as Bessie – are listed as assistants to their mother Isabel, the dancing teacher. Norah died unmarried in 1942 in Surrey. The third, Ethel, died in New Jersey in 1914 (I think). It was the youngest, Fanny/Bessie, who came to Canada.

She married a musician, Dalton Baker, in England in 1905. They moved to New York in 1913. In 1914, they came to Toronto. Dalton became organist and choirmaster at Timothy Eaton Memorial Church where, many years later, I was christened, and a teacher at the Royal Conservatory of Music, where, many years later, I sweated through music exams.

In the 1930s, the family moved to British Columbia, where Dalton taught until his retirement. They had children, and their descendants still live on the west coast of Canada.

Perhaps when her mother Isabel died in 1920 in London, Fanny/Bessie inherited the plaque. She may have left it in Ontario when she moved with Dalton and their two children to British Columbia. Somehow, it came into the possession of Norman’s friend, and Norman bought it when he was a graduate student (in those days, he supplemented his graduate school scholarships by buying and selling antique documents and objects). And then it sat in a box in our basement until a couple of weeks ago.

I realize that this blog has strayed from Paris, but at this time of the year, the First World War tends to dominate my thoughts. Every November 11, at the local cenotaph, I remember my two great-uncles who died in the First World War, as well as ten men from Perth Academy in Scotland who had come to Canada before the war and enlisted here. Now I will add Archie’s name to my list. According to the bronze plaque, the men (and women) died for freedom and honour. Or maybe they died out of a sense of duty and comradeship. Or something else entirely. No matter. They all deserve to be remembered.

Text and photograph of plaque by Philippa Campsie. Map from Gallica. Photograph of Joseph Marryat Palliser from ancestry.com. Photograph of Dalton Baker from Footlight Notes blog.

*Theresa Jill Buckland, Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 81.

As always, loved your gem of a blog.

Without asking divulgence of any professional secrets (!), may I ask how/where you accessed the war diary for the 23rd Battalion? I’m often ‘digging around’ WW1 and WW2 but I am unsure of how to tap into such sources as the one you used here.

Many thanks in advance.

Graeme Wright (Winchester, Va.)

Dear Graeme,

The war diaries for the First World War are available through ancestry.com. There is even a special search function, and once you get the hang of it, you can zero in quite specifically (I admit it took me a few tries). In some ways, it was access to resources like the diaries that made me decide to take out a subscription to ancestry.com.

All the best,

Philippa

Many thanks, Philippa. I’ll look into that.

Kindest regards.

g

Amazing story – excellent sleuthing. How wonderful to be able to bring to light the story of a soldier who died so many years ago as well as his family.

The capabilities of online research never cease to amaze and enthrall me!

Thank you for this fascinating story. It links together so many things from the 1st World War, to family history, to how the medal came to Canada and to finally how it came into Norman’s possession

________________________________

I was amazed at what there was to find out, starting with a single name!

Fantastic research and a highly entertaining read too. Thank you so much for sending the link to this wonderful blog.

And thanks to you for your help. Sometimes it takes a village to write a blog….

Philippa

Thank you for this moving and timely essay.

Marsha Huff

So glad you enjoyed it.

You can stray from Paris, after all it’s your blog! An interesting read. Thank you.

Of all the 1.3 million plaques, I was lucky to stumble across one with a story attached!

Beautiful (and impressive sleuthing)! Merci. This is a family with a lot of unmarried children. I thought it was intriguing. We complain today about children staying too long with their parents but, obviously, this was also the case in the past. And the names ringed French: Bizet, Michau, Egville. Were they from France or was the name better for advertising dance lessons?

Regarding the Tarantula music, you would enjoy the French movie Tous les Soleils and the music for it. I have the CD if ever you are interested to listen to it one day. I used to say it was the music of my soul. Maybe less lately but I still love it.

Encore merci!

Yes, the family was originally French but settled in England. Thank you for the movie recommendation, which sounds great. I shall try to find it online. Some of the music is on YouTube. Hope all is well with you.