On a recent trip to London, we visited the Slightly Foxed Book Shop on Gloucester Road. We recommend it highly.

One of the treasures Philippa acquired there was They Eat Horses Don’t They? The Truth About the French by Piu Marie Eatwell. It introduced us to the story of the Onion Johnnies of Brittany and how they came to represent Frenchmen and Frenchness to generations of English and Scots.

A few days later, when we were visiting some of Philippa’s relatives in Scotland, they recounted childhood memories of seeing Onion Johnnies in Glasgow and Dundee. A story that was utterly new to Philippa and me was very familiar to her Scottish relatives.

Who were the Onion Johnnies? They were itinerant onion vendors who came from Brittany to sell their famous pink onions in the U.K., primarily England and Scotland. They arrived in the U.K. in late July or early August and stayed until Christmas or early January.

Back in Toronto, we located a wonderful book called Onion Johnnies: Personal Recollections by Nine French Onion Johnnies of their Working Lives in Scotland. It represents an astounding effort by the Scottish Working People’s History Trust and the European Ethnological Research Centre.

It’s not clear how or when the trade started, but references to French onion sellers in England and Scotland go as far back as the late 1820s. All the Johnnies seemed to come from Brittany, particularly from Roscoff and neighbouring villages such as St Pol de Léon, Plouescat, and Santec, where the distinctive onions were grown.

Life in Brittany has never been easy (in a previous blog we mentioned the vicissitudes of the sardine catch) and the area grew more onions than the regional market could absorb. Exports were necessary.

At first, Onion Johnnies travelled to Great Britain by sailboat with a cargo of freshly harvested pink onions and perhaps some shallots and garlic. Later, ferries and trains replaced the sailboats. According to Eatwell, the Anglo-French trade carried on by the Onion Johnnies “peaked in the late 1920s—when 9,000 tons of onions were sold in England by 1,400 Johnnies—before gradually petering out.”

Many in the onion trade were connected by family ties. The Johnnies were organized with ouvriers (workers) under a patron (boss). The patron had to find a shop or warehouse to serve as a base for storing and preparing the onions for sale, as well as to provide rudimentary living space for the sellers. The patron also determined the daily quotas that the ouvriers had to sell, some of whom were less than 10 years old.

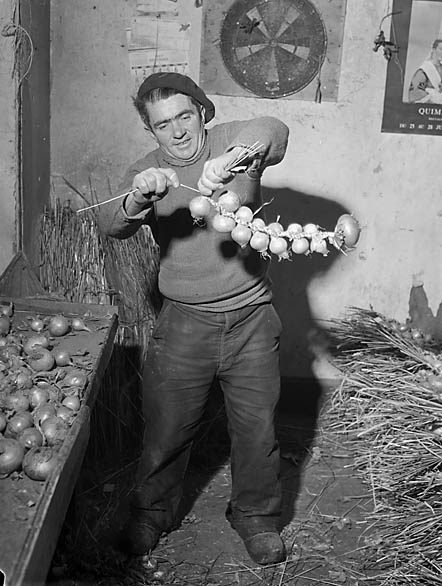

Ouvriers pushed two-wheeled hand carts or charrettes and then loaded sticks, or batons, with onions. They carried the batons over a shoulder, going from house to house, and knocking on doors. A freshly loaded baton could weigh as much as 50 or 60 pounds, providing the Onion Johnnies with strong incentive to sell the onions quickly.

Living conditions were spartan. Home base was often an old shop, lined with stacks of onions. When eight-year-old Jean Saout arrived in Glasgow in the 1920s, his father was a patron. Jean recalls that they used a big shop. “My father and I and all the Onion Johnnies slept there… We slept on straw and we had blankets to cover ourselves with… But you slept well, you slept well.”

In 1930, 13-year-old Jean Milin began working full-time as an Onion Johnny in Leith:

There were no beds—only straw… we all slept together in a row on the straw, like herrings or sardines! I was the youngest and I was in the middle of the row. You had covers, blankets. But we also had a sack or bag to sleep in—a sleeping bag. Oh, it was very comfortable. We were there all together, quite warm in the straw, so we didn’t feel the cold.

The facilities included a small kitchen, a table to eat on, a tap with running water, and (wonder of wonders) a flush toilet downstairs. Not all the Onion Johnnies enjoyed such amenities.

Conditions improved somewhat in the late 1940s. Some Johnnies who worked out of vans and were away for more than a day stayed overnight in hotels that bought onions from them. However, they were the exception. Yves Rolland was a teenage Johnny who worked from a base in Maritime Street, Leith, in the 1960s. “The shop was full of onions. So at that time we slept in very cramped conditions. Have you ever had rats running on top of you?”

The young ouvriers received no cash for their work; their share was sent home to their parents. Those who were paid directly generally received wages only at the end of the onion-selling season. No wonder that when householders asked the cost of onions, the ouvrier would give the price and then say, “and a penny for myself.”

The days could be long, as ouvriers seldom returned to home base until all the onions were sold. Looking back on his work as an ouvrier in Leith in the 1950s, Yves Rolland could remember leaving the shop at five in the morning and not returning until “about half past-ten at night.” But, he added, “that wasn’t a normal day’s work. It depended how lucky you were. But normally it was round about seven or eight at night we used to finish. Most days the leaving time from the shop or the base was from about six, half-past six in the morning.”

The long hours of Monday to Friday were shortened on Saturday to midday or mid-afternoon. Sundays were for “stringing the onions or…gathering rushes from the fields for stringing them.” Straw or hay from nearby fields could also be used.

Numerous photos show Onion Johnnies with strings of onions slung over bicycles, which by the 1930s were replacing handcarts and batons. It was still hard work, as some routes covered long distances with a heavy load. After the Second World War, vans became more common, They “were employed as mobile depots from which the Johnnies, lifting out their laden bikes once that day’s destination was reached, could pedal their rounds and return to the van again for fresh supplies if needed.” Onion-laden bicycles also travelled on trains and tramcars.

Were the Onion Johnnies “representative Frenchmen”? To many people, Onion Johnnies were stereotypically French: beret, bicycle, and striped shirts (although the photographs we have seen show them wearing darker, more practical clothing and some wear brimmed hats, not berets). But they represented a specific culture within France, not the whole of France. Moreover, many of the original Onion Johnnies spoke Breton, a Celtic language similar to Welsh, rather than French.

What strikes me most about the accounts is the hard work they did. Jean Milin summed it up with “We Onion Johnnies were always working. It was a hard life.” Claude Quimerech stated, “We simply didn’t have plenty money! It was very hard, very, very hard.”

Jean Saout strikes one as a thoughtful workman. In 1965 when he was 52 years old and had been an Onion Johnny in Glasgow for more than 40 years, he retired from the job, but not from working.

Well, I never got rich selling onions, ah, no! I just made enough to live on and to drink a little glass of wine. But I never wanted to change my job, never. I never had any ambitions to do any other job like being a seaman or working on the railways. It was the same when I was working the other months of the year with the vegetables at home in Brittany.

Years later, aged 86, he told an interviewer,

The life of the Onion Johnnies was hard—and it was hard for their wives and families at home, too. But you had to live as best you could. I wouldn’t like to begin all over again, though at least one doesn’t have to sleep on straw any more! I don’t regret having worked as an Onion Johnnie at Glasgow. But it was a hard job, too hard.

Whenever we get nostalgic about the past, we do well to remember how hard things were for many people. The sight of an Onion Johnny pushing his bicycle may conjure up “the good old days” for many in England and Scotland, but this was hard, lonely work for little pay, with only a sack of straw to sleep on at night.

Text by Norman Ball. Photos from Wikimedia; except for the final photograph above, which is from Buffalo Dandy; apparently the Buffalo Lazy Randonneur Club sponsors an annual Johnny Onion ride in September – photographs from the 2014 event are delightful.

Quotations, unless otherwise credited, from Ian MacDougall, Onion Johnnies: Personal Recollections by Nine French Onion Johnnies of their Working Lives in Scotland, Tuckwell Press, 2002. I am grateful to the Scottish Working People’s History Trust and the European Ethnological Research Centre for helping me see French history more fully.

They Eat Horses Don’t They? The Truth About the French by Piu Marie Eatwell, was published by Head of Zeus Press, 2013.

Roscoff in Brittany has a museum called “La Maison des Johnnies,” where you can explore the history of these hard workers. Here is a leaflet from the museum.

What a hard way to earn a living! But since a living must be had, you did what you had to do. Thanks for another interesting article.

This was fascinating! I’m going to forward this story to my parents who grew up in N. Ireland in the .30’s and 40’s to see if they have any memories of Onion Johnnies.

Welcome to the club.

I picked up Piu Eatwell’s book at a reading by her at the American Library in Paris a couple of years ago. Onion Johnnies were only one of the many subjects she covers, which range from smoking, film, and food to, of course, sex. Oddly, for a book about the French written by an Englishwoman, it was printed in Germany.

Unfortunately, like many books published these days, it lacks an index.

Barney Kirchhoff, an American in Paris for 37 years. and

I remember them when I was a kid growing up in the north of England. The onions were good too, a Cheddar cheese and raw onion sandwich is still a favourite. As far as we were concerned a typical Frenchman wore a beret and rode around on a bicycle with a string of onions. The odd thing is that I have a couple of Breton friends and they were unaware about this trade until I showed them a newspaper article (in English).

And now the pink Roscoff onions are famous and have AOC status. I’m sure the memory of the Onion Johnnies influenced this.

Beautiful story. Thank you.

Marc Piel

This brought back other memories long forgotten , the rag and bone man “any old iron? Any old iron?” with a poor old horse and cart.

As usual, Norman, a lovely tidbit from the past. Thanks to you both!