Let it never be said that archival research is dull. My recent forays into the archives at the Institut national des Jeunes Aveugles uncovered a crime nearly 200 years old, and a con man who exploited a legal loophole to get rich. And thanks to the internet, I was able to follow the two malefactors to see what became of them (since neither was ever prosecuted for wrongdoing).

Let’s start with the con man or, more accurately, the snake-oil salesman. His name was Sebastien Guillié. He was born in Bordeaux in 1780 and studied to be a doctor, specializing in ophthalmology, receiving his degree in Paris in 1806. By then, he was a married man. His first job was as a military surgeon attached to Napoleon’s army in Spain.

His story gets a bit murky after that. He was imprisoned for a year in Vincennes following a failed coup d’état in 1812 by General Claude-François de Malet, who tried to seize power while Napoléon was otherwise engaged in Russia. According to some accounts, Guillié was mistaken for a General Guillet and arrested in error. He was eventually released for lack of evidence tying him to the conspiracy. (Malet was executed for treason.)

The fall of Napoleon and the restoration of the monarchy rescued Guillié’s career, and in 1814, presumably because of his medical expertise in diseases of the eyes, he was appointed director to the school for blind youth. He even seems to have been recognized by the Legion of Honour (look at his lapel pin), heaven knows why. He had not particularly distinguished himself.*

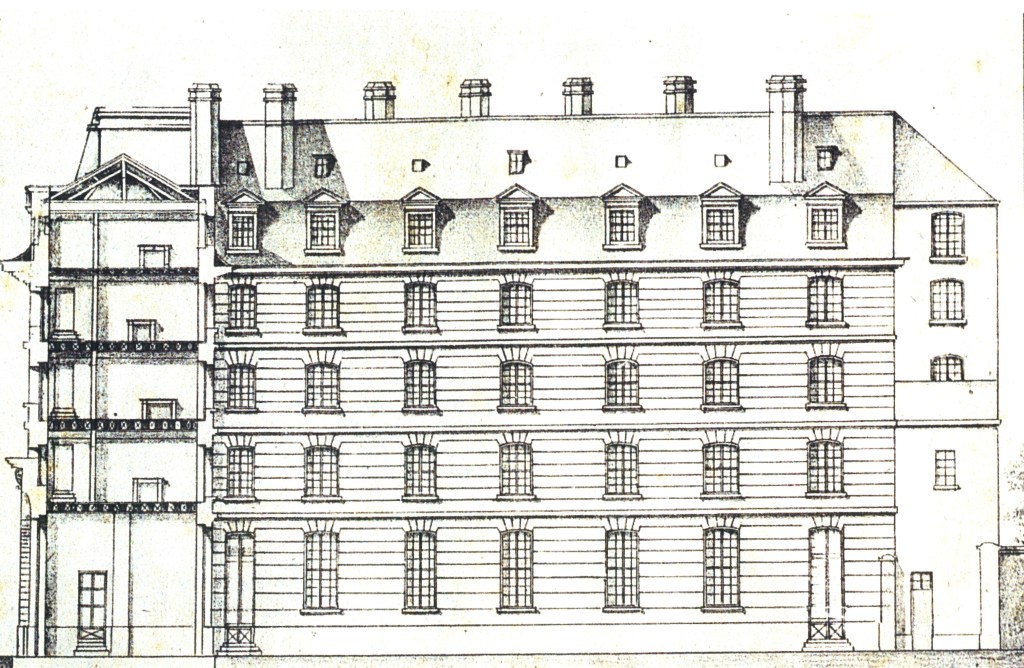

If you read my last blog, you will know that not all those associated with the school found him congenial. He moved the school into a disused seminary on the rue St-Victor – a grim, damp, building that undermined the health of many of its inhabitants. One of Guillié’s own infant daughters died there.

As associate staff, he recruited two young people from his home town of Bordeaux – Pierre-Armand Dufau, aged 20, and Zélie Cardeilhac, aged about 17, who had training in music.

Guillié knew how to put on a show. He held regular events at which the students demonstrated their abilities in front of an audience. The director who succeeded him wondered how the students learned any new skills when they spent so much time in performance. Guillié also published a volume titled Essai sur l’instruction des aveugles, ou Exposé analytique des procédés employés pour les instruire (Essay on the instruction of the blind or Analytic exposition of the procedures used to instruct them). The front page trumpets: “Printed by the blind and sold for their benefit.” Ahem. The book was actually printed by a commercial printer, J.-L. Chanson, whose name appears on the very last page. In the book, Guillié even states that the school’s printing equipment had been destroyed in 1812. (According to another source, Guillié himself sold it to raise money.) And was the book really sold for the students’ benefit? I do wonder.

The book contains illustrations of healthy-looking young people engaged in all sorts of useful toil, although, like the printing press, some of the workshops did not, in fact, exist at the school at that time. Here is basket-weaving. Apparently, this was not an option for the students at the school.

Guillié carried out painful experiments on the eyes of some of the students. I’ll spare you the details. He was also a stern disciplinarian and the children were sometimes chained up for infractions of the rules. Naturally, that sort of “procedure used to instruct them” did not make it into his book.

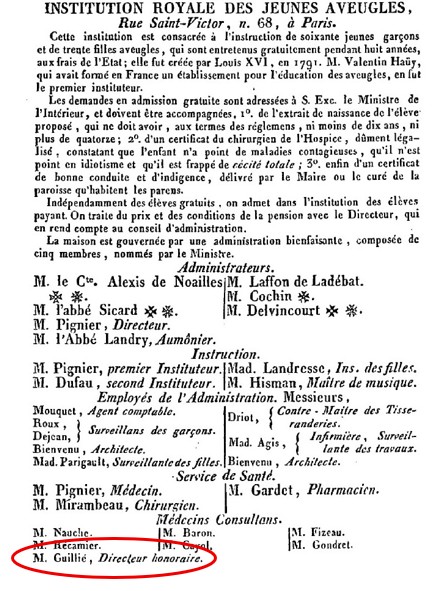

Guillié was asked to leave the school early in 1821. Ostensibly, the reason was his affair with Zélie Cardeilhac (she left at the same time). But that story doesn’t quite add up. If he had left in disgrace, why then was he still listed as “honorary director” of the school in the Almanach Royal for the next two years? The following entry is from 1822, after a new director had been appointed.

What did he do next? Histories of the school have nothing to say about his later life. So I thought I’d start at the end of his life and work my way back to 1821. I discovered that he had died in October 1865. I even found a photograph of him as an older man, taken earlier that year.

He died in the small town of Asnières-sur-Seine to the west of Paris. (This was good news. The birth, death, and marriage records of the City of Paris itself were destroyed in 1871, and despite heroic attempts over many decades at reconstituting those documents using information from families and church parishes, details are often sparse. But Asnières kept its records safe.) I found a complete death notice for Guillié, including his profession, address, time of death, and – here it gets interesting – witnesses.

One was Hippolyte Martin Cardeilhac, a lawyer. Aha. The link to the Cardeilhac family had apparently continued. Hippolyte Martin turned out to be Zélié’s brother. The connection offered a clue.

Gallica, the online portal of the National Library of France, has a nifty little feature in the “Advanced Search” option. You can search for two words or names occurring close together in a document, and narrow it down by date. I searched for the combination of Guillié and Cardeilhac during the period between 1821 and 1865. Bingo.

In the Annuaire-almanach du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de l’administration (basically a city directory), from the 1840s to the 1860s, O. [sic] Guillié, ancien médecin (former doctor) and Madame [sic] Zélie Cardeilhac, former teacher at the Institut des Jeunes Aveugles, were living at 7, rue de Monsigny. During certain years, her brother the lawyer was also at the same address. The building is still there, and now functions as a hotel.

I spent a little time digging into the Cardeilhac connection, using the French genealogical website Filae. I had found only a death notice in the name of Zélie Cardeilhac, but now that I had the name of her brother, I found her family and her full name: Marie Thérèse Catherine. She was the eldest of four children, born in 1797 in Bordeaux, and the only daughter. Her father was a church musician, hence her early training in music.

Filae also supplied the interesting information that she had given birth to a daughter in 1831, named Sébastienne (!) Augustine Thérèse. The child’s father’s name is given as Jean Auguste Jaurès, a négociant (businessman). She was 33, he was 24. They were not married. She lived at 7, rue de Monsigny; he lived at 15, rue de Paradis Poissonnière (it’s a good 25-minute walk away). If he was the father, I will eat my hat. (He later went on to marry someone else, but Zélie’s child took his name.) Oh, and the birth was attended by another of Zélie’s brothers, a doctor.

All this was deeply interesting, but I needed to get back to Sebastien Guillié. What had he been doing all those years?

The answer emerged in an obituary. Guillié was well enough known that there were obituaries, but not well enough liked for them to be complimentary. Here is the story, told by Doctor Louis Balthazar Caffe in La France médicale:

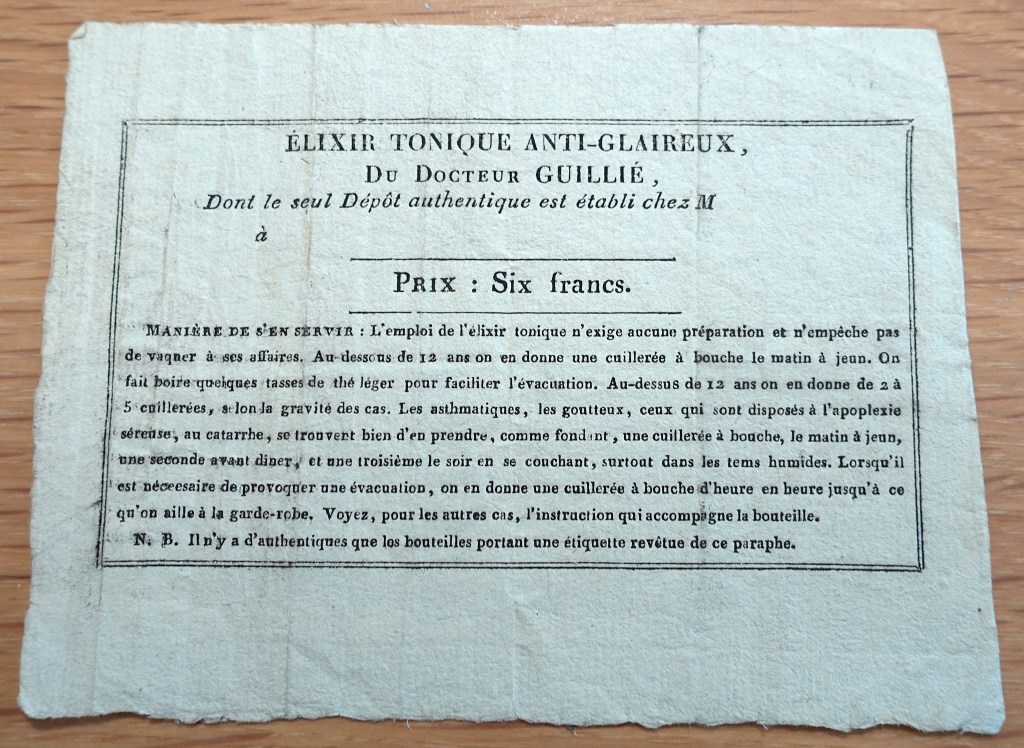

Guillié, who had a great deal of education seasoned with a great deal of intelligence, one day became impatient with his lack of riches – a fate he shared with many of his most estimable colleagues – while he saw many idiots, ignoramuses, and rogues growing rich around him. Clients who … paid him poorly and constantly told him that they were bothered by phlegm (which is only a symptom and not an illness), inspired him … with the dastardly idea of prescribing them an anti-phlegm elixir. He had only to choose from the numerous formulas of purgative spirits available in German and other pharmacopoeias; but for commercial success, it was necessary to make people believe in a secret remedy. … The law prohibits the announcement of secret remedies (incidentally, it is worth repeating that there is no secret remedy, chemistry sees to that), so Guillié buys a dying newspaper, inserts the formula for the said anti-phlegm elixir, confiscates all the copies, and immediately puts the paper out of business after making a simple legal deposit. The law remains, from then on, satisfied and powerless. By this cruel revenge against human stupidity, Guillié realizes 80,000 francs in income.

I had seen one of the advertisements in the archives, and although I had photographed it, at the time I had no idea what it represented.

The earliest mention of Guillié’s elixir that I can find dates from 1822, so this must have been Guillié’s main source of income after leaving the school.

One mystery remains. The so-called elixir, now in pill form, was still being sold a hundred years later, in the 1920s. Who got the profits? Zélie Cardeilhac died in 1879, also in Asnières-sur-Seine; Guillié’s estranged wife had died in 1866 in Paris. Most, perhaps all, of the children of their marriage died young; if not, I cannot trace any survivors. Who’s left? The descendants of Zélie’s daughter Sébastienne. She married advantageously (a sub-prefect in Aisne), had two daughters, who also married, and survived into the 20th century. But that is pure conjecture. Perhaps an enterprising pharmacist bought the rights to the “secret” formula.

Let’s move on to our thief. It’s a shorter story.

This one started, for me, as a whodunnit. A history written in 1849 of the school mentions “un agent comptable” (accountant) who disappeared in 1831, taking with him about half a year’s worth of the school’s receivables.** The fact is also mentioned in a document handwritten by the director in 1833, but neither mentions the name of the thief.

I also found a letter written to the director in June 1831 by the head of the board of governors, Alexis de Noailles. Alexis was a born diplomat, with seldom a bad word to say about anyone, but he bursts out: “Vilain homme ! Voler des pauvres, des aveugles, compromettre une administration qui a confiance en lui !” (Dreadful man! To steal from the poor, the blind, to compromise an administration that had confidence in him!”). I had to know more.

I found the accountant’s last name in the archives; he was referred to as Le Sieur de Rubat, and he’d been hired in 1823 (one of two candidates for the job). But I needed his first name to trace him. Nineteenth-century French records are parsimonious with first names. It’s all Monsieur This and Madame That and most people seemed to sign letters with their last name only.

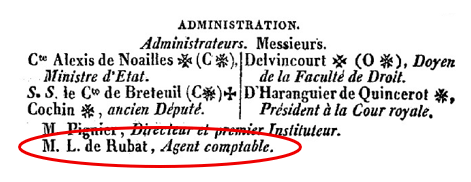

I found a clue in the Almanach Royal. In its list of administrators and employees at the school, it provided an initial (L.) – a bit odd, since they did not offer anyone else’s initial, and de Rubat is not such a common name that he might be confused with another accountant called de Rubat.

In any case, the initial allowed me to narrow my search and eventually I found him: Louis Prosper de Rubat, born in 1795, probably in Paris. In 1823, the same year he secured his employment at the school, he married Marie Angelique Bisson. The couple had two sons. Their first son died in infancy in the countryside, where he had been sent to be wet-nursed – a common custom in those days. Marie Angelique died in November 1830, after giving birth to a second son in March 1830.

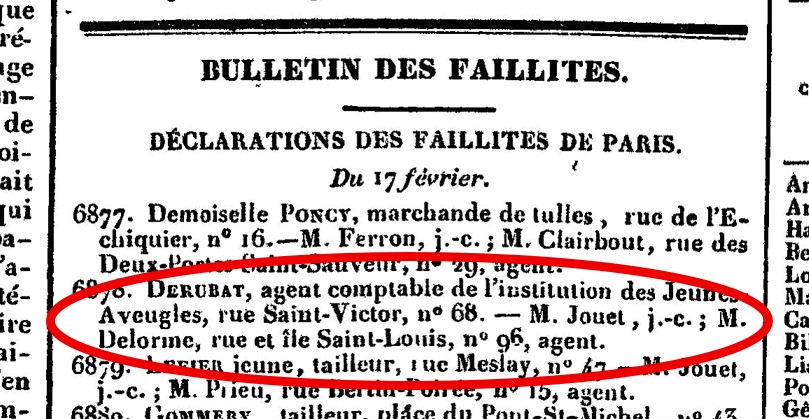

Was her death the source of his money troubles? In any case, de Rubat declared bankruptcy (faillite) three months after her death, in February 1831.

And a few months after that, he leaves town with the Institut’s money. Where did he go?

Not that far, actually. Brussels. (Belgian and Dutch records can be found on Open Archives.) He seems to have settled down quite well with his ill-gotten gains. He remarried a woman 23 years his junior in 1836, had two more kids, a boy and a girl, and set up some kind of business (he appeared in Belgian records as a “négociant” or merchant).

I found records of the weddings of his Belgian son and daughter and wondered what had happened to the remaining son by his first wife: Alphonse Alexandre Raymond. All I could find was a record of Alphonse de Rubat, aged between two and three years old, who died in a Paris hospice in February 1833. Was that him? If so, his father abandoned him in his flight to Belgium.

Louis Prosper de Rubat died in Brussels, probably safely in his own bed and surrounded by his loving family, at the age of 83. Le vilain homme.

Text by Philippa Campsie. Photographs of Guillié from the Wellcome collection; image of the school from the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles; photograph of rue de Monsigny from Google Street View, photograph of Elixir advertisement by Philippa Campsie; lithograph by H. Walter of Brussels in 1855 from Wikimedia Commons; document excerpts and illustration from Guillié’s book from Gallica.

* I found nothing in the online database of the Légion d’Honneur and my email to the Légion archivist has not yet been answered.

**Joseph Guadet, L’Institut des Jeunes Aveugles de Paris (Paris: Thunot, 1849), page 91.

Fascinating – many thanks.

Thanks for reading the blog. I appreciate your comment.

You are a veritable Sherlock Holmes.

What a convoluted story!

What I found so interesting is the fact that the French government actually had an anti-snake-oil law!

What a tremendous work of research! Chapeau!

Enjoyed every minute of it. Thanks for writing in.

Fascinating as usual!

Thank you

Olive

Get Outlook for Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg

Glad you enjoyed it. Thank you for reading it to the end!

I love it when you catch a scent and hunt down such interesting stories! Xoxo

And I love it when readers go down the rabbit hole with me. Thank you so much.

Reading this research on Sébastien Guillié reminded me how powerful it is to dig beneath the surface of history — to discover the real, messy, human stories that often remain hidden.

Here in the Khumbu, on the trails to Everest Base Camp, we live surrounded by such stories. Most trekkers come to see the world’s highest mountain, but few truly hear the voices of those who make that journey possible — the Sherpas, the porters, the cooks, and the families who call these harsh valleys home.

I think often of the porters who climb with loads heavier than their own bodies, walking the same dangerous paths every day. They know the mountains like family — every bend, every stone, every sound of a shifting glacier. And yet, their names are rarely remembered. We’ve lost so many to avalanches, altitude, and exhaustion — fathers, brothers, daughters. Their stories too often vanish into the wind.

And then there are the Sherpas, who carry more than physical loads — they carry the spiritual and cultural heart of these mountains. They guide not just with ropes and ladders, but with quiet wisdom, with prayer flags at the passes, with rituals at the monasteries to keep climbers safe.

When Sir Edmund Hillary summited Everest with Tenzing Norgay, it was more than a climb. It was a crossing of worlds — a beekeeper from New Zealand and a Sherpa from Khumbu, forever bound by a shared triumph. But what Hillary did after is perhaps even more important: he came back, not as a climber, but as a builder. Schools, hospitals, bridges — real lifelines for the people here. That’s the kind of story that changes how we see this place.

Like your work piecing together Guillié’s life from old archives, we too are trying to gather and preserve these human histories — the laughter and loss, the resilience and rituals — before they fade. Because for every towering peak, there is a human story at its base. And those stories are what truly give Everest its soul.

https://www.himalayaheart.com/blog/difficulty-of-mount-everest-base-camp-trek-what-you-need-to-know