I have recently returned from a 10-day research trip to Paris for a book on Charles Barbier. Over the years, I have pegged away at this project, taking a day here, a day there for research during our visits, but the more I learned, the more I realized I needed to learn. So I went to Paris in May. Robert, the archivist at the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles (the school for the blind in Paris) was welcoming, Norman encouraged me to go on my own, and I fitted in a visit to my family in London on the way there.

All in all, I spent six days in the school archives. Once the gardien at the front gate had made a note of my presence and my passport number, I was free to come and go every day, passing the statue of Valentin Haüy as I crossed the courtyard every morning.

The archives are housed in a sunny room with windows on both sides, right underneath the music department. As I worked my way through a series of archival boxes, I listened to students practising piano or playing for their teachers. I liked the sound, even though I heard the strains of Für Elise rather a lot. Many played the way children do – rushing through the bits they know and slowing down when they hit a difficult patch. It always made me smile. Later in the day, I heard saxophone and once, drums (I left a bit early that day; listening to drummers practise can be wearing).

What I learned in six days suggested that I really need about six months to do a thorough investigation, but I brought away dozens of scans and photographs and photocopies, and I am working my way through them. I wanted to know more about the school and its workings in the early 19th century. I had read Barbier’s correspondence with the school director in the 1820s, but that told me only part of the story.

I spent almost two days studying the agendas and minutes of the Conseil d’Administration (the Board of Governors) in the 1820s and 1830s. Much of the discussions dealt with mundane matters like the price of bedsheets and the quality of the food, but this was all part of the running of a residential establishment. I discovered that the school had had the misfortune to have not one, but two unscrupulous accountants in succession, Mouquet and de Rubat (French administrative documents never give first names, which makes people hard to trace), who embezzled funds. I would have loved to dig into that story a bit more, and perhaps one day I will, but time was short and there were other stories that needed my attention.

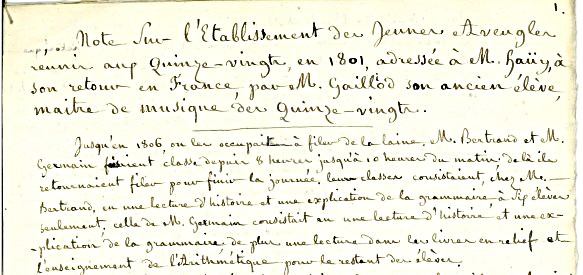

In a box containing a variety of documents from different sources, I found a 12-page report that looked promising. I have just finished a transcription of the scans. It is one of the liveliest bits of writing I have encountered so far. Here are the first few lines.

The author is Jean-François Galliod (1777–1852), who taught and directed music at the Quinze-Vingts hospice for the blind. In 1801, the school for the blind had been merged with the Quinze-Vingts. This report, which describes life at the school from 1802 to 1815, was addressed to the school’s founder and Galliod’s former teacher, Valentin Haüy, who had left France in 1802, travelled to Russia to teach there, and returned in 1817. Galliod himself was blind and he dictated his account to his teenaged daughter, Victoire Augustine Eugenie.

The Quinze-Vingts is now a modern ophthamological hospital, but it retains its original gate (shown below from inside the enclosure) and its chapel.

Galliod’s report is like a long letter to a good friend. He even calls him “Papa Haüy” at one point. In commenting on the people around him, he’s candid and sometimes cheeky, but not spiteful. Clearly, in the early days at the Quinze-Vingts, the teaching at the school was at a low ebb. The director, Louis Bertrand, was pleasant but disengaged. When Galliod mentions the efforts of the students to avoid his lectures, one gathers that they were eye-wateringly dull. Bertrand’s second-in-command, Paul Seignette, was much more supportive and helpful.

The rest of the teachers were a mixed lot. I laughed aloud at the story of M. Gèneresse (the spelling of people’s names tended to be rather creative in those days, so I have no idea if that’s what it really was). Here is Galliod’s description (my translation):

M. Gèneresse taught only grammar, one lecture [a week], and the composition of letters. M. Gèneresse came from the colonies specifically to teach French grammar, which he learned I don’t know where… He used a book. Whenever one said something that didn’t appear in his book, he would say, “My friend, you know nothing.” He once asked a student to give an example of a proper name. The student responded, “Bordeaux.” [Gèneresse replied] “You don’t know what you are talking about. Paris, the Seine, those are proper names.” From this we knew that at least he could read. He knew a bit of music, which was of no use to us. He left in 1815…

At first, Galliod taught music to individual students. His role as music master for the school, and the creation of a choir and orchestra had informal beginnings:

In 1802, my friends expressed the desire to sing in the chapel of the Quinze-Vingts. I brought together all your old students… I showed them with some difficulty the bass part of the mass we used to sing. That wasn’t all; many of my old schoolfellows were not at the Quinze-Vingts, so I had to go and rehearse with them at their homes. They lived on the rue St. Denis or thereabouts. Mornings I worked at the Quinze-Vingts; in the afternoon, I took one of my sighted music students and gave him my arm to get to the quartier St. Denis, where I taught each person his or her part. From there I went to the Café des Aveugles. Our major rehearsals took place at the Quinze-Vingts. We performed the mass on Easter Day, and later at the Blancs Manteaux. We continued to perform it several times at the Quinze-Vingts.

The chapel is one of the few survivors of the old Quinze-Vingts. This is a picture of the interior.

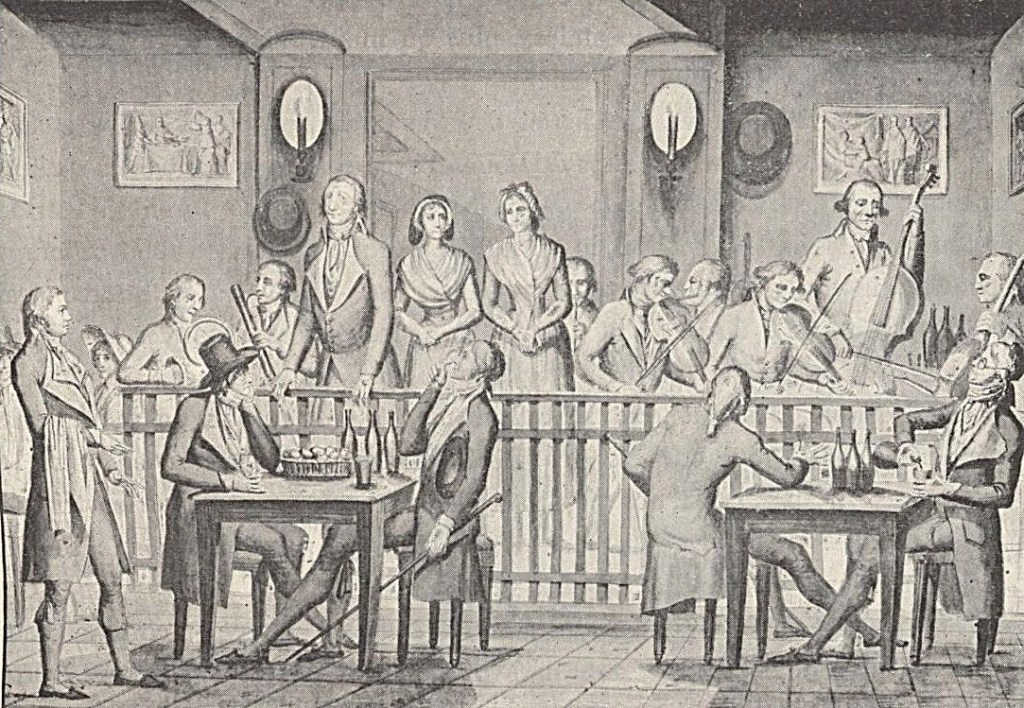

At the Café des Aveugles in the Palais Royal, blind musicians entertained the patrons, so Galliod probably had some friends there.

And Notre-Dame des Blancs-Manteaux was a church in the Marais, not far from the Quinze-Vingts. This drawing is from 1877; I gather it was rebuilt in the mid 19th century and would have looked rather different in Galliod’s day.

In 1804, the group learned a mass setting for four voices by the composer Jean-Baptiste Métoyen. The composer expressed doubts about the choir’s ability to learn it. But with the help of a sighted music student to interpret the score (this is long before the days of braille musical notation), the choir learned it in time for All Saints’ Day in November.

The choir even performed for a visit by the pope. At the time, Pope Pius VII was living in exile in France, so this is not quite as impressive as it sounds, but he came with a clutch of cardinals. The choir sang in Italian, Latin and French and the pope distributed rosaries to the participants.

In 1806, M. Seignette, the second-in-command, asked Galliod to become the official music instructor for the school students. Galliod accepted. Three of the older students, who played violin, bass, and clarinet, pitched in, and Galliod figured out the rest, learning to play other instruments alongside his pupils. Seignette helped him obtain more instruments, to give the students some choice in what they learned to play. And so an orchestra was formed, with violins, cellos, basses, flutes, oboes, clarinets and horns. Later they added bassoons.

Galliod composed an overture for the orchestra that allowed each of the best players to do a small solo. It must have taken some time, teaching each group its part individually, and then putting it all together. One student, Noël-Jean Ismann, could see a little and was able to read musical scores. (Ismann went on to become a music teacher at the school himself.) By 1808, the orchestra was playing Haydn symphonies.

In 1811, Galliod formed what he calls a “harmonie,” meaning a band made up of wind instruments and percussion. It included serpents (shown below) and a bass drum. When some of his star players left the school, he rounded up a couple of violinists and gave them oboes. Within a few months, they were part of the band.

In 1814, Seignette asked Galliod if the choir and orchestra could perform Vivat in Aeternum by Nicolas Roze. This was a big piece performed at the coronation of Napoleon. You can hear it on YouTube and it’s pretty impressive. Galliod went to see Roze, taking his daughter and Ismann with him and a letter of introduction asking for copies of the music for a motet and the Vivat.

He [Roze] asked me, why do you want them? I said, to sing at the chapel in the Quinze-Vingts. He asked, by whom? I said, by blind people. He asked, how are you going to do that? I explained as best I could and he gave me the score with considerable hesitation, telling me that we were not to perform it until he had conducted a rehearsal. He asked, when could he come to hear it? I told him M. Seignette would write to him. We learned the motet that precedes the Vivat and the Vivat in a week. We informed M. Roze. He came right away and found us assembled. He was very surprised to hear the motet and Vivat he had given us performed by blind people…he had expected it would take us a month to learn.

On the feast day of St. Louis in August 1814, the group successfully performed a concert of this work. Galliod next planned a Te Deum for double choir in December.

And then he injured his leg. He couldn’t get to the Palais Royal where his musical friends were gathered, so he stayed at the Quinze-Vingts and taught the musicians there, sitting down, with his foot on a stool. When the leg got so bad he couldn’t walk, he called a friend, gave him a broom handle, and asked him to make a crutch. The rehearsals continued, but the musicians were struggling, so he sent for M. Roze, who was happy to continue working with the group. The two of them, working from nine in the morning to one in the afternoon each day, rehearsed the music. Galliod got his daughter to help the women singers learn their parts. On December 29, they performed the Te Deum and a mass in front of the Grand Aûmonier (the senior priest in charge of the Quinze-Vingts) to the satisfaction of the administrators.

By this time, Nicolas Roze had become one of the group’s most enthusiastic supporters, and he took over rehearsals while Galliod recovered.

Galliod persisted, staging concert after concert, despite losing some of his best players to an orchestra that entertained people in the gardens of Versailles. Then came the big blow. M. Bertrand died in March 1814 and was replaced by a doctor named Sebastien Guillié. Galliod remarks, dryly, that “[the death of ] Bertrand was regretted by some of his students; it was regretted even more when they came to know Monsieur Guillié.”

No kidding. At a concert for the archbishop in January 1815, Guillié asked Galliod what salary he wanted to remain as music director for the school. Galliod replied, 800 francs. Galliod says Guillié haggled as if he were buying apples and eventually offered 500 francs. When Galliod refused, Guillié demanded the keys to the music cupboard. Before handing them over, Galliod asked to remove instruments and tools in the cupboard that were his personal property. Guillié and Mouquet (remember Mouquet? one of the two dishonest accountants?) grabbed the rest of the instruments, threw them pêle-mêle (pell-mell) into a sack, and took them away. The school moved to separate quarters in February 1815.

Galliod continued to conduct the choir and orchestra at the Quinze-Vingts, and after Guillié was fired from the school in 1821, Galliod came and helped out with the music program there from time to time. He knew Charles Barbier and helped publish a couple of books using Barbier’s raised-point writing method, which was popular at the Quinze-Vingts. I was saddened to find out that Galliod’s loyal and helpful daughter died in 1824 (when she was about 26). Galliod composed music that seems to have been lost, but inspired generations of musicians, who went on to become teachers and performers, not just at the school, but in many other places. He deserves to be better known.

Text by Philippa Campsie, images of Café des Aveugles, chapel interior, serpent, and Roze from Wikimedia; drawing of Notre-Dame-des-Blancs-Manteaux from the Musée Carnavalet; photographs of INJA and the gate of the Quinze-Vingts by Philippa Campsie. Many thanks to Robert Pradère, archivist at INJA, and to Mireille Duhen of the Association Valentin Haüy, who helped me with my research and answered my questions.

A wonderful set of stories, Philippa. Research with original documents is so exciting! You must have felt at some moments that you were back in the early 19th century with them all.

Actually, I still do. My head remains firmly in early 19th-century Paris!

Indeed! He does deserve to be better known! Thank you for this tidbit from your research, and I look forward to learning more as your research and writing unfolds.

I’ve been creating Wikipedia articles for certain of the individuals in the story, just to make use of material that I can’t use in the book, but that has informed my understanding of the period. I expect I will do one for Galliod eventually.

Such great research…..makes you feel as if you are part of that period.

The stories reveal interesting bits both about running such a school in that era and about attitudes towards blindness. Does the name “Quinze-Vingts” have any particular significance?

Pingback: Cold cases: The snake-oil salesman and the thief | Parisian Fields