When our friend Mireille in Paris asked me to research the descendants of Valentin Haüy, the man who pioneered education for blind children, my first reaction was, “Wait – he had children?” I knew about Haüy’s work with blind students. But I’d somehow missed the fact that he had children of his own.

I pass his statue every time I visit the archives in the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles. But the young man at his feet is his first student, François Le Sueur.

Historians have lots to say about Haüy’s relationship with Le Sueur, and with other, later students. Information about his family is sparse. The Wikipedia article makes no mention of wife or children, and notes that he spent the last years of his life living with his brother, René-Just, a noted mineralogist. They sound like two old bachelors bunking in together.

René-Just was a priest, and so, yes, a bachelor. But Valentin was a husband and a father. In his biography of Haüy, historian Pierre Henri relegates details about Haüy’s two wives and his progeny to an appendix I’d never bothered to examine. It was a start.

Haüy was 29 when he married for the first time in 1774 at St-Germain l’Auxerrois in Paris. His wife, Elisabeth Victoire Vaillard, was about 21. The record on Filae (the French genealogical website) transcribes her name as Taillard, which is reasonable, if you look at the records. Variant spellings, creative handwriting, and inaccurate transcriptions make genealogical research in this era a challenge.

The couple had a daughter in 1775, and named her Catherine Madeleine Victoire Justine.

By that time, Haüy had had the experience that inspired him to educate blind people, but he had not begun to act on that ambition. In 1771, he visited the Fair of St-Ovide, held in what is now the Place de la Concorde. There, he saw a group of blind men dressed in long gowns and pointed hats, pretending to make music on instruments they could not play, performing in a café for the amusement of the customers. This appalling display was the subject of an engraving.

As the story goes, Haüy was angered by the way in which the blind were being mocked and resolved to do what he could to ensure that blind people could find more dignified ways to earn a living. After all, deaf children were already being taught at a dedicated school founded in Paris in 1760. Why not blind children?

But first, Haüy needed to establish himself in society and earn some money. He was a linguist and translator (reportedly he spoke 10 languages), and became interpreter at the court of King Louis XVI in 1783.

The following year, he persuaded the Philanthropic Society to sponsor his plan for a school to teach blind children to read and write. Although most accounts suggest that Haüy met a young blind beggar, François Le Sueur, and selected him to be his first student, the respected historian Zina Weygand states that the teenaged Le Sueur got word of the scheme and sought out Haüy himself.

However the two actually met, the resulting relationship was fruitful. Le Sueur made rapid progress learning to read books with raised lettering, in a form invented by Haüy. The picture of a smartly dressed Le Sueur reading a book by touch adorns the cover of the English translation of Weygand’s book, The Blind in French Society.

Haüy opened a day school for boys and girls in his own house on the rue Coquillière. We can now imagine Haüy’s wife there, too, along with his 10-year-old daughter.

The students gave demonstrations of the skills they had acquired in reading and music, and their presentation in Versailles led to royal endorsement of the school in 1786. That year, the school moved to rue Notre-Dame-des-Victoires.

Just as things were going so well, Haüy’s wife died in 1788, at the age of 35, leaving him with a 13-year-old daughter. That must have affected him. Did he send the daughter to live with relatives, or did she remain with him?

Meanwhile, he had to contend with the political upheavals of the Revolution. Since royal endorsements no longer had value, the school needed a new form of state support. In 1791, the government proposed the merger of the schools for the deaf and the blind. It probably seemed like a good idea at the time.

That same year, Haüy married again, to Louise Marguerite Allain. I found a record of her baptism in Rambouillet in 1772.* She would have been 19 to Hauy’s 46 years. How do you suppose Haüy’s 16-year-old daughter felt about her new stepmother?

The couple had a son the following year, Philodème Just Haüy, born during the Reign of Terror (his first name means “lover of the people” – politically correct in Revolutionary times). The stress on Haüy at this time can only be imagined. He was trying to keep control of the school he had founded in the face of authorities who were determined to regulate the establishment with a heavy hand, and he had a young wife, a baby, and a teenaged daughter to protect. He was even imprisoned briefly, and although he was eventually freed and his name cleared, he lost his day job as a translator in the Maison des Postes.

His daughter, Catherine Madeleine Justine Victoire (I don’t know which name she used regularly) left home in 1795, when she was 20, by marrying the son of a bailiff.

Meanwhile, the merger with the school for the deaf proved a failure and the school for the blind was moved to a convent that had once served as a shelter for women. The school was now known as l’Institut des Aveugles Travailleurs (the Institute of Blind Workers, emphasizing the youngsters’ roles as labourers and minimizing their role as students).

In 1798, Valentin’s wife gave birth to a stillborn girl.

Eventually, the school was forced to merge with the Quinze-Vingts, the hospice for adult blind people, shown below. Haüy wrote letters of protest, but the plan went ahead in 1800, and the students were subject to harsh discipline in the new situation. Haüy tried to provide them with some measure of education, thereby taking them away from their labours. The authorities viewed this as insubordination.

In 1801, Haüy’s wife had another son, Adel Theodore Vincent de Paul Haüy, who died in infancy. (Note the inclusion of a saint’s name. St. Vincent de Paul was the patron saint of Haüy’s school. It was a brave choice at a very secular time.)

Finally, in 1802, Haüy’s school job was abolished, and he was offered a small pension. He was 57, responsible for a wife (who had recently lost two children) and a 10-year-old son.

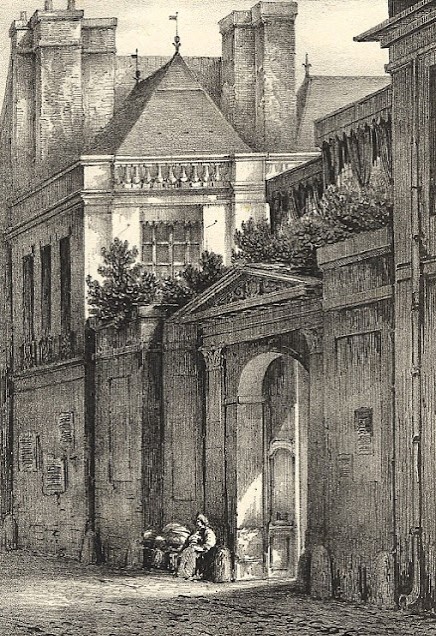

He opened what was first called a Lyceum for the Blind and later, oddly, a Museum for the Blind and School for Languages in the Hotel de Mesmes, shown below, on the rue St-Avoye (now part of the rue du Temple). To make ends meet, he took in only paying students from well-off families. It wasn’t a success.

In 1806, at the invitation of the tsar, he left for Russia with his wife and 14-year-old son and a former student, Alexandre Fournier, hoping to found a new school there. On the way, he stopped in Berlin and his discussions there contributed to the foundation of a German-language school for the blind.

Russian was not one of the 10 languages Haüy knew (although most educated Russians spoke French), and he attracted few students. Nevertheless, he stayed until 1817, perhaps because he disapproved of the Emperor Napoleon’s reign in France, perhaps because there was no work in France for him.

Haüy’s son, Philodème Just, however, flourished in Russia, where he was known as Just Valentinovich Haüy. He became an engineer, and in 1820, aged 28, he married Caroline Horson de Forville, 24, whom Pierre Henri describes as a marquise. I regarded that information with great suspicion until I found a document for the marriage of their son which used the term “Marquis Herson de Forville.”

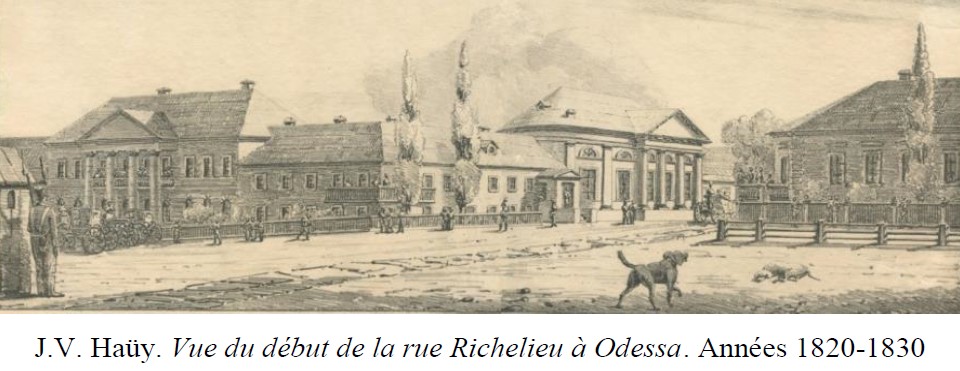

Just Haüy is held in great regard in Odessa. He designed at least one bridge, contributed to the supply of clean water, and conducted research on the prevention of landslides. He was also something of an artist and the sketch shown below is attributed to him. He and his wife had two children, a girl and a boy, and they carried on the family name. I was able to trace their descendants to the present day.**

But back to our beleaguered Valentin. He returned to France in 1817, with his former student Fournier, but without his son, and presumably without his wife. He went to live with his brother René-Just.***

The principal of the re-established school for the blind, Sebastien Guillié (Zina Weygand calls him a “despot”), refused to let Haüy visit the premises. But Guillié was fired in 1821 for having an affair with a female teacher (he was not missed), and his successor Alexandre-René Pignier, did his best to repair the relationship with the founder.

On July 19, 1821, the feast day of St. Vincent de Paul, Haüy was invited to visit the school, then located on the rue St-Victor (Haüy did not live to see the building that his statue now graces). He returned a month later for a special concert in his honour. He was overcome with emotion as he listened to the children singing.

Valentin Haüy died on March 19, 1822, at the lodgings in the Jardin du Roi that he shared with his brother. He was 76 and had been unwell for some time. His brother died two and a half months later. They are buried together in Père Lachaise.

The tomb includes the names Vuillemot and Rougeron. Vuillemot was Valentin’s daughter’s married name; Rougeron was his granddaughter’s married name (she married in 1821 and may well have included her grandfather in the celebration). It seems that both families contributed to the creation of the grave, and I hope this means that the daughter and granddaughter maintained their relationship to the end of Haüy’s life.

Does it make a difference to our understanding of Haüy’s work when we include his family members? I think it does. He had family obligations, experienced widowerhood and a second (probably unhappy) marriage, and would have taken pride in his son’s accomplishments and his granddaughter’s marriage. Nobody writing a biography today would exclude the family context. But Haüy is usually viewed as if his only relationships were professional or political ones, and all the highs and lows of his life related to his work. It’s time to restore him to the family circle.

P.S. While we’re at it, what about the other fellow in the statue, François Le Sueur? Well, in 1793, aged 27, he married Marie Louise Thérèse Mesnard. She was seven years older than he was and also blind. She came from Rambouillet (like Haüy’s second wife). He died in 1810, aged 44, while Haüy was in Russia. She died in the Quinze-Vingts in 1841, aged 82.

Text by Philippa Campsie; image of Hotel de Mesmes from https://histoire-bibliophilie.blogspot.com/2019/07/; sketch by Just Haüy from https://www.persee.fr/doc/casla_1283-3878_2016_num_14_1_1136 (page 56); all other images from Wikimedia Commons.

The two main sources of information are Pierre Henri, La Vie et l’Oeuvre de Valentin Haüy (Presses Universitaires de France, 1984), available only in French and Zina Weygand, The Blind in French Society from the Middle Ages to the Century of Louis Braille (Stanford University Press, 2009), a translation of Vivre sans Voir (Créaphis, 2003). The story about Le Sueur appears on page 94 of the English version. Weygand mentions, but does not name, Haüy’s wives and children in her account of his life and work.

*The record gives the father’s name as “Allais” instead of “Allain” and the mother’s as “Giraud” (elsewhere spelled Girault). The original document is not available for view on Filae, only a transcription, but it appears to be the correct record.

**Although Haüy’s daughter married and had a daughter of her own who married, all of the children of that marriage died in childhood. So his present-day descendants are related to his son, Just Haüy.

***Haüy’s widow, Louise Marguerite Allain Haüy Menié, died in 1856, aged 84. She had remarried in Marseille three years after Haüy’s death.

Thank you for this fascinating research! I look forward to seeing your work in my “in box,” and love learning from your shared passion for Paris.

I love it when I find a new story (or a new aspect on an old story) that hasn’t been told before. And to think that this one was right under my nose!

I love reading your stories. If I am ever fortunate enough to visit Paris, I will use you as my guide. 🦋🙏. Merci beaucoup.

your stories are so interesting.

Thank you sooo much! I love reading your works!!

God bless, C-Marie

Pingback: Louis Braille and the Legacy of a Writing System – The Writers' Spot

Hi Philippa

Thank you for researching this fascinating story.

Olive

Pingback: The music master | Parisian Fields