The church of Sainte Jeanne de Chantal at the Porte de Saint-Cloud in the 16th arrondissement is a striking example of mid 20th-century architecture. With its dome and tower, it almost looks like a mosque with a minaret.

You enter a large, austere sanctuary. Up near the front are two small arched doorways.

When you walk through one of the doorways, you find a jewel of a chapel surrounded by beautiful modern stained glass windows.

We spent a long time examining the windows and reading the panels beside displays about the life of Sainte Jeanne de Chantal – she sounds like my kind of saint, down to earth and independent-minded – and about the building of the church.

What caught my attention was the fact that the church had been bombed during the Second World War, when it was still unfinished (construction had started in the 1930s). Parts of it had to be rebuilt in the 1950s and it was completed only in 1962.

We sometimes prefer to overlook the fact that Paris was bombed in the Second World War, perhaps because it is embarrassing to remember that (unlike the First World War), it was the Allies doing the bombing, in their efforts to weaken the German occupiers. Some histories of the German occupation of Paris in the Second World War barely mention air raids and bomb damage. After all, the big story was the saving of the city by the German commander, Dietrich von Choltitz, who disobeyed Hitler’s orders to destroy Paris.

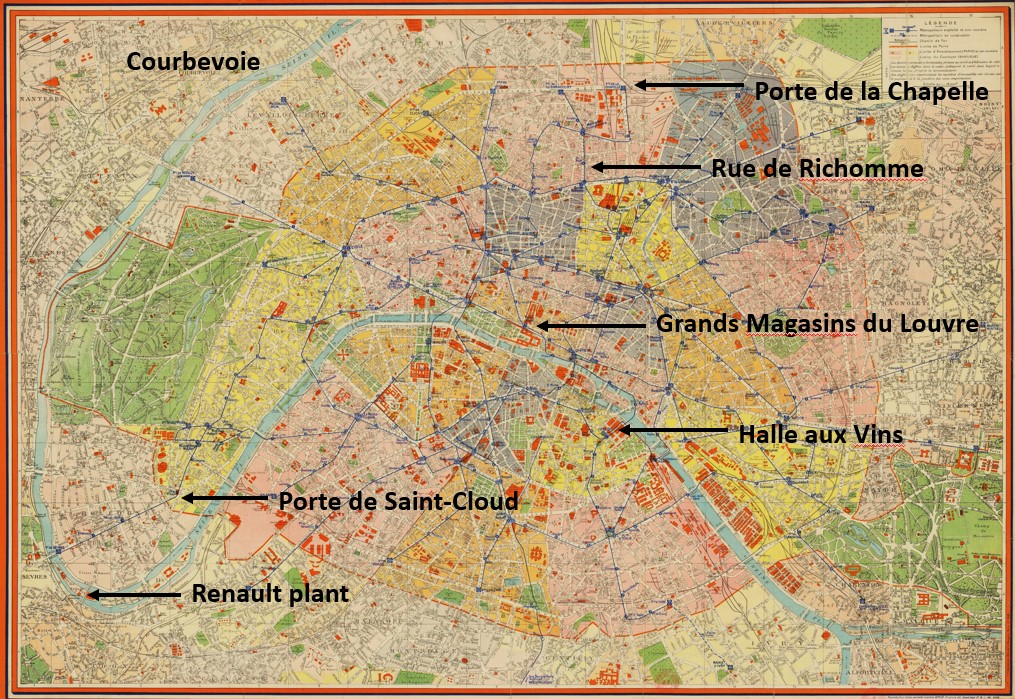

Other accounts suggest that most of the bombing happened in the poorer districts to the north and east of the city, rather than the prosperous 16th to the west. But the church at Porte de St-Cloud was close to the Renault factory on the Ile Séguin in the Seine and other industrial sites, which were strategic targets for the bombers, and the 16th came in for some collateral damage. Here are the sites mentioned in this blog, and they are spread across the city.

Only much later was I able to find out exactly when the church had been bombed. A wartime newspaper that I found on Gallica mentioned the church as one of several damaged or destroyed sites in the 7th, 15th, and 16th arrondissements after heavy bombing by the United States Air Force on September 15, 1943.

Most of the bombing occurred during 1943 and 1944. Before that there were only two major air raids over Paris: one on a factory in Chatou (a western suburb, not shown on the map) in June 1940 and the other on the Renault plant in March 1942. But in the following two years, the city was bombed repeatedly. In one case, an Avro Lancaster was hit by anti-aircraft fire from the German occupiers and crashed on to the roof of the Grands Magasins du Louvre on September 23, 1943. All seven crew members, four of them Canadian, were killed, and the building was extensively damaged.

The very last day of bombing was August 26, 1944, and that one time, it was the Germans bombing the allies and members of the Resistance who had secured the city as the occupiers were fleeing. That raid killed about 190 people and demolished more than 400 buildings, including the Halle aux Vins, which burned to the ground. Perhaps since it was a one-off, it is mentioned only briefly in passing in a couple of books I have about the occupation and liberation of Paris.*

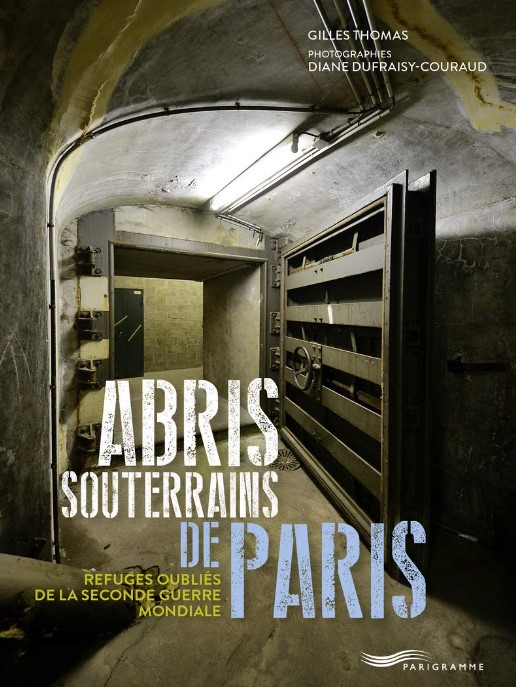

A week or so after our visit to the church, I wandered into the Paris Historique building on the rue François Miron in the Marais. I was immediately drawn to a book called Abris souterrains de Paris : Refuges oubliés de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale (Underground shelters in Paris: Forgotten refuges from the Second World War) by Gilles Thomas with photographs by Diane Dufraisy-Couraud.**

I opened the book at random, and was fascinated to find this photograph of people sheltering in the Metro, just as Londoners had sheltered in the Underground during the Blitz.

It made sense. Some of the stations are deep underground. The book also noted that different stations were designated for the French and for the German occupiers. That, too, made sense.

As in London, Métro stations were only one type of shelter. Certainly, there was no shortage of underground spaces available – Paris has a vast network of tunnels, sewers, catacombs, and quarries underneath the city. The Germans used some of these spaces for storage and other purposes, and the Resistance fighters used them for escape routes and clandestine operations of all kinds.

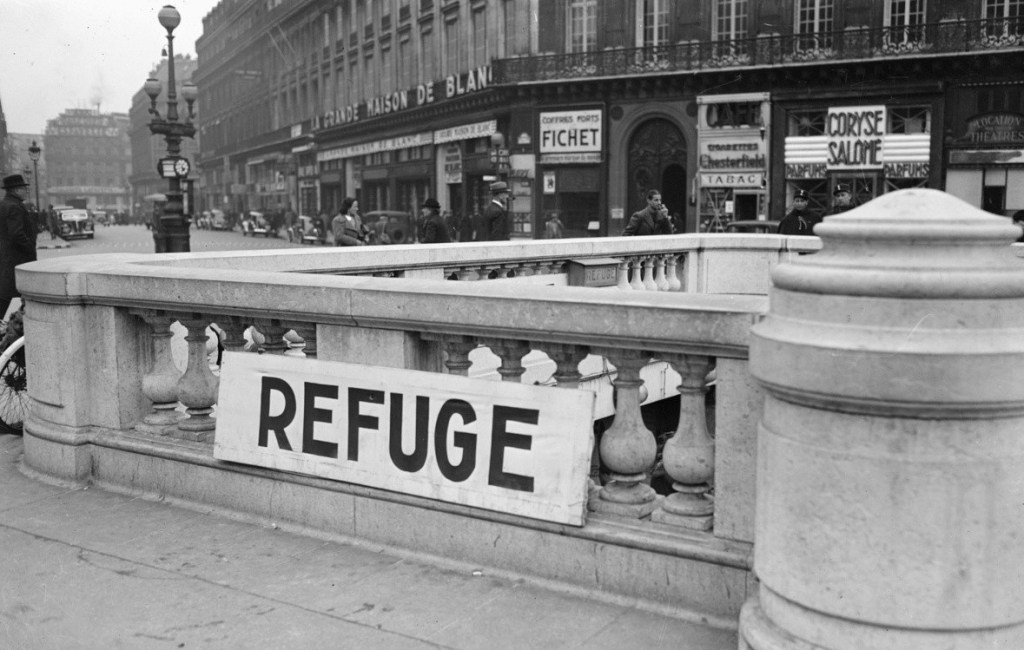

One big concern in wartime was poison gas, and provisions were made to seal off the underground shelters if need be. The book shows all kinds of arrangements for making spaces air-tight, and mentions that as in England, residents were expected to carry gas masks.

Despite these provisions, known collectively as “Défense passive,” many Parisians died in air raids, and many buildings were destroyed. The raid that damaged the church of Sainte-Jeanne de Chantal killed about 300 people.

The following image of the rue Richomme in the Goutte-d’Or district, showing Sacré-Coeur and the Dufayel building in the background, was taken after a particularly destructive raid by the Allies on April 21, 1944.

An aerial photograph from December 31, 1943, shows damage to the suburb of Courbevoie. Those dark objects at the top of the photograph are falling bombs.

The book about the shelters includes comments from people who remembered the war. Here is an example (this and the following quotations are my translations):

At the end of the Occupation, I was living a few hundred metres from the Gare du Nord. During the night of April 21 to 22, 1944, the Allies’ air forces bombed the marshalling yards at La Chapelle. I took refuge in the basement of my building. But the din of the explosions was so bad that to this day I cannot abide the sound of fireworks. (Philippe Bouvard, quoted in the Figaro magazine, July 22, 2016.)

Others were less troubled:

In offices and above all in schools, the siren constituted a break or even a welcome recreation. The schoolchildren, conducted by their teachers, hurried to the shelters reserved for them, in a joyous brouhaha; they left in the hope that classes would not resume. (Pierre Audiat, Paris pendant la guerre, Hachette, 1946.)

In some cases, it depended where you lived:

Each quartier had its own approach: in the 5th, which was rarely touched by bombs, nobody considered going down to the basement during an alert. By contrast, in the Batignolles or Montmartre, ever since the terrible bombing of [April] 21, [1944], all the inhabitants, at the first sound of the siren, hastened to the depths of the Métro, clutching small suitcases containing their most precious belongings. (Jean Galtier-Boissière, Mon journal pendant l’Occupation, La Jeune Parque, 1944.)

To this day, sirens across France sound on the first Wednesday of each month. That is just to test that the alert system works. The sirens would sound in earnest in the case of a major disaster, from a dam break to a release of toxic gas. But in 1943 and 1944, they heralded bombing raids. Although Paris did not suffer nearly as much as London did during the Blitz, it was not spared entirely. Residents of both cities knew what it was to wait underground while the bombs came down, wondering what they would find when they emerged.

Text and photographs of church interior by Philippa Campsie; photographs of Pyrenees and Opera (refuge) stations: https://www.paris.fr/pages/paris-sous-terre-ces-refuges-oublies-de-la-seconde-guerre-mondiale-8124; plaque: https://openplaques.org/plaques/39943; all other photographs from Wikimedia Commons.

* In one, this event is described in a single paragraph beginning, “The sense of victory was disturbed Saturday evening when the Germans attacked Paris from the air.”* If I’d been a tenant of one of those buildings, I would have been more than just “disturbed.” Jean Edward Smith, The Liberation of Paris: How Eisenhower, de Gaulle, and von Choltitz saved the City of Light (Simon & Shuster, 2019), page 191. In Ronald C. Rosbottom, When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light under German Occupation 1940–1944 (Little Brown, 2014), the event rates a footnote only (page 336).

**Parigramme, 2017. The quotations are from pages 32, 48, and 94.

Hello,

Your blog is so interesting! Thank you for this post.

Yes, this bombing of Paris is taboo. As well as the bombings of Belgium (were I was born) by the Allies. It helps a lot to understand these historical facts. Thank you for your contribution.

By the way (if I may use this expression here!), but in a quite different perspective, I suppose that you know Bruno Latour’s book on (in)visible Paris. If not so, you might enjoy it:

http://www.bruno-latour.fr/node/93.html

Best wishes,

Anne-Nelly Perret-Clermont

Switzerland

Thank you for the comment and the link. I certainly need to read Latour’s book.

Thank you for your interesting article – great to see the photographs as well. Recently, Liberation of Paris walking tours have been offered in Paris, one of which I took. The walk began in the Luxembourg Gardens, headquarters for the German Luftwaffe during the war. Thank you for your research and interesting article!

Stephen Morgan

Portland, Oregon USA

That tour sounds interesting. I would like to take it on my next visit.

Very, very interesting, great research, and what a marvelous church!!!!

Thanks, Linda, and happy Mother’s Day. Hope you feel better soon.

A fascinating subject, and one that is important to remember. Civilian populations are always put at risk in war. A good friend of ours who was only 4 or 5 years old when Paris was occasionally being bombed remembers the sirens of the “alerte” and going with her mother down into the metro at Pigalle. She also told us that she once laid out her little schoolbag, dolls and some food on the dining table. Her mother asked her what she was doing. “Je joue à l’alerte, Maman!” Ah, resilient children.

Thank you for that extraordinary story. Children are amazing!

Hi Philippa Thank you for this look at history. It makes you wonder about those poor people in Gaza and the terror they are having to deal with on a daily basis as the Israelis unleash their bombs on them. Olive

Indeed, and the poor people of Ukraine as well.

Fascinating! I had never thought about Paris being bombed. Thank you sharing this important aspect of wartime Paris.

Always interesting and informative. Hope you are both doing well. My old man turned 80 this year and I am barking at his heels. It is this year our 50th wedding anniversary. dawnmonroe05@gmail.com

Good to hear from you. Congratulations on your 50th anniversary! We are well, thank you. Have a good summer.