How far is St. Helena from a little child at play?

What makes you want to wander there, with all the world between?

Oh, mother, call your son again, or else he’ll run away,

(No-one thinks of winter when the grass is green!)

I cannot remember how I first encountered this poem by Rudyard Kipling, but when I was a teenager, I set five of its eight verses to music. The poem recounts the story of Napoleon Bonaparte from the perspective of his final years, but the first verse might apply to anyone who went to that remote island in the Atlantic. What makes you want to wander there?

That line came to mind during a recent conversation in which I learned that the great-great-great-grandfather of one of the churchwardens at St. James Cathedral in Toronto had gone with his battalion to St. Helena in 1816 to guard Napoleon Bonaparte. The ancestor’s name was William Kingsmill. He spoke French and at some point, conversed with the imprisoned former emperor.

This image of Napoleon on the Bellerophon, the ship on which he formally surrendered to the English after his defeat at the battle of Waterloo in 1815, was painted in the 1880s by my great-grandfather’s cousin, Sir William Quiller Orchardson. The Bellerophon took Napoleon from Rochefort on the west coast of France to Plymouth in England after his defeat at Waterloo. Napoleon, who had hoped to find refuge in England or the United States, was not allowed to disembark and was sent into exile instead. Another ship, the Northumberland, took him to the remote island of St. Helena in the Atlantic; he arrived in October 1815.

William Kingsmill arrived in 1816. He had been born in Kilkenny, Ireland, in 1793, and served with the 66th Regiment of Foot from the age of 16. He was 24 when his battalion was sent to St. Helena to keep an eye on Napoleon. About three thousand British soldiers were stationed there during this time – I can’t help wondering how they spent the days, with only one prisoner to guard.

Willam kept busy by starting a family. His English fiancée, Hannah Pinnock, had decided not to wait for his return to England, and joined William on St. Helena. They married in February 1817.*

How far is St. Helena from an Emperor of France?

I cannot see—I cannot tell—the Crowns they dazzle so.

The Kings sit down to dinner, and the Queens stand up to dance.

(After open weather you may look for snow!)

St. Helena was a long way from Napoleon at the height of his power, shown above in a painting by Jacques-Louis David, which takes up a whole wall in the Louvre. On St. Helena, Napoleon stayed at first in a two-room pavilion, while Longwood, the house where he lived until his death in 1821, was being renovated.

Longwood, shown above, was inland, about four miles from the capital, Jamestown. The location was windy and foggy and the house was often damp. It had been divided up into many small rooms to accommodate Napoleon, his retinue of servants (butler, valets, footmen, cooks), and three of the four associates who followed him into exile, along with several of their family members (the fourth lived nearby with his wife and children).

How far is St. Helena from the field of Waterloo?

A near way—a clear way—the ship will take you soon.

A pleasant place for gentlemen with little left to do.

(Morning never tries you till the afternoon!)

At first, the former emperor did have plenty to do, and spent much of his time dictating his memoirs to one of his associates. He was allowed to walk freely in the grounds during the daytime and he had a large bathtub in which he took long, hot baths every day. He could, and did, receive visitors. He ate and dined quite well, although he rarely spent more than twenty minutes at table for a meal. At one point, he cultivated a garden (or oversaw the cultivation of a garden). But as time wore on, he became more and more inactive.

William Kingsmill, a junior officer and a married man with a growing family (he and Hannah had three children in St. Helena), chose to remain on the island when other members of his regiment returned to England. The Kingsmills apparently knew the members of Napoleon’s circle quite well. This is clear from an incident described in Napoleon in Exile: St. Helena (1815–1821) by Norwood Young, published in 1915:

Napoleon was so pleased with his new gardens that he was jealous of any intrusion upon them. One day he perceived a goat and two kids in the outer garden, and learning that they belonged to Madame Bertrand, who was much out of favour, he sent for his gun and shot the goat. To save the kids Madame presented them to Mrs. Kingsmill, the wife of Lieut. Kingsmill, of the 66th, the officer in charge at Longwood Guard (p. 183).**

Madame Fanny Bertrand*** was the wife of Henri-Gratien Bertrand, one of Napoleon’s associates who had accompanied him into exile. The family lived in a house near Longwood. Fanny was “out of favour” for a variety of reasons (tempers often flared in the claustrophophic atmosphere of captivity and Fanny was headstrong), but partly because Napoleon disapproved of her association with the wife of the governor, Sir Hudson Lowe. Napoleon loathed the governor, who was strict in his supervision and regulation of Napoleon’s activities.

William Kingsmill’s name appears in a list of people who supported Lowe in a feud with Dr. Barry Edward O’Meara, Napoleon’s Irish-born physician. Although O’Meara was part of the British contingent in St. Helena, he came to sympathize more and more with his patient, and he wrote letters to officials in England that criticized Lowe’s actions. O’Meara left the island in 1818, but the feud continued when he published an account of his time there that offended Lowe; those who had been there at the time had to take sides. Kingsmill sided with Lowe.

How far from St. Helena to the Gate of Heaven’s Grace?

That no one knows—that no one knows—and no one ever will.

But fold your hands across your heart and cover up your face,

And after all your traipsings, child, lie still!

Napoleon died at Longwood on May 5, 1821, probably of stomach cancer (opinions differ on the cause of death). Of his friends, two had left the island by then, but Bertrand and Fanny had remained. The former emperor was buried in a valley near Longwood with full military (but not imperial) honours.

The members of the 66th Regiment prepared to return to England. The Kingsmills went back with them, and a fourth child, a son, was born in Sunderland, England.

The battalion then went to Ireland, where two more Kingsmills were born. In 1827, the battalion was sent to Canada; two more Kingsmill children were born in Québec. William Kingsmill eventually resigned his commission and he and his family went west to what is now Ontario. The youngest son, Nicolas, known as Nicol, was born in Port Hope in 1834. This son is the great-great-grandfather of my friend in Toronto.

About this time, popular sentiment in France changed. Napoleon was remembered with fondness and pride. This change led to a petition for the repatriation of his remains. In 1840 his body was exhumed from the valley in St. Helena, transported to Paris, and entombed with great ceremony in Les Invalides. This event is called “Le Retour des Cendres” (literally, the return of the ashes, although Napoleon had not been cremated and it was his body that was brought back).

One of those chosen to oversee the transfer from St. Helena was Henri-Gratien Bertrand. He was now a widower, Fanny having died in 1836. This image of the casket arriving at Courbevoie was painted by Henri-Felix-Emmanuel Philippoteaux in 1867:

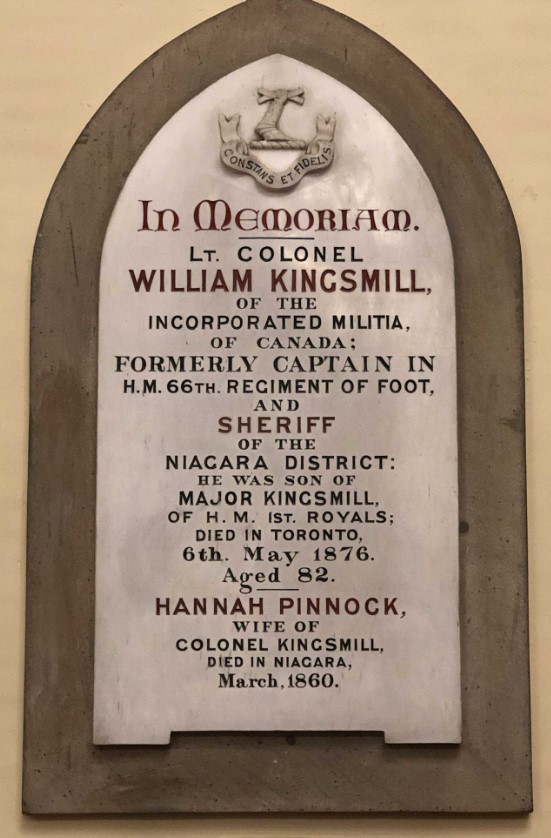

Meanwhile, William and Hannah moved to Niagara-on-the-Lake. William, who had reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Canadian militia, became Sheriff of the Niagara district. This is a portrait of him in later life.

Hannah died in Niagara-on-the-Lake in 1860, William died 16 years later in Toronto, at the home of his son Nicol. His body was taken by steamer back to Niagara-on-Lake for burial beside Hannah (not quite as grand as Le Retour de Cendres, but a solemn boat trip nonetheless). A plaque hangs in St. Mark’s Church in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

In 1840, news of the Retour des Cendres probably reached William and Hannah Kingsmill in Canada. How did they feel about their experience in later years? Perhaps they wondered: Did we really meet a former emperor on an isolated island in the Atlantic? Did he really shoot that goat? Or was it all a dream?

No-one thinks of winter when the grass is green.

Text by Philippa Campsie. Orchardson painting from the Tate Gallery website; David painting from Wikimedia; image of Longwood from Saint Helena Napoleonic Heritage website; photograph of grave on St. Helena from Wikimedia; Philippoteaux painting from L’Histoire par l’Image website. Thanks to Christian Kingsmill and Joseph Cairns for images and information about William and Hannah Kingsmill.

For more on Napoleon’s time in St. Helena, see Brian Unwin, Terrible Exile: The Last Days of Napoleon on St. Helena (London: I.B. Taurus, 2010).

* This part of the story reminds me of my grandmother Dora. She was preparing to travel from her native Yorkshire to Vancouver, where her fiancé had settled, when the First World War broke out. Like Hannah Pinnock, she chose to brave the Atlantic rather than wait. I am sure both Hannah’s and Dora’s families pleaded with them not to go, but they made up their minds and that was that.

**The same story appears in William Forsyth and Hudson Lowe, History of the Captivity of Napoleon at St. Helena, 1853, volume 3, page 206.

***Françoise Elisabeth (Fanny) Bertrand, née Dillon, was the daughter of another Irish-born military man, General Arthur Dillon, who served in the French Army, fought in the American War of Independence, and was executed during the French Revolution because of his loyalty to the king. She spoke fluent English, hence her friendship with Hannah and Lady Lowe.

I have seen Napolean’s coffin in Paris but didn’t know much about his final days. Thanks for this fascinating post.

If you can find the book by Brian Unwin, it will tell you a lot. I learned a great deal from it. So glad you enjoyed the blog. Philippa

Very interesting what with the connection to Canada.

This is why I love family history. You never know what sort of connections will emerge! Best, Philippa

Hi Philippa Thank you for sending me this little bit of history with a personal connection to you and your St James community. and The Irish connections were of particular interest to me. They were obviously of the Anglo Irish protestant class who were enablers of the British in Ireland. There had been a revolution in 1798 in which the French were involved. Unfortunately for the Irish, there were terrible storms and the French were unable to land and the revolt was savagely crushed. I think I read somewhere that Napoleon was slowly poisoned…as you said, there are different theories circulating about the cause of death. All the best Olive

Sent from my Bell Samsung device over Canada’s largest network. ________________________________

It would seem we share a great great great grandfather. JJ Kingsmill is my great great grandfather. Have you read the two books William Penned? They are housed in the U of T library, but available online. A few years back, I saw him mentioned in a law journal article penned in the 1960s praising William for his compassion treatment of prisoners while a sheriff in Guelph.

Yes! it is true that Napoleon killed an animal, but it was not a goat, but one of the oxen of the Compagnie des Indes. And Yes ! he was with Arthur Bertrand, son of Fanny Bertand.

Arthur Bertand wrote 20 years later:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5579591g/f109.item

The garden which occupied the Emperor’s leisure time, and where he came to wander his sad reveries, was often ravaged by the Company’s oxen, which escaped and came to eat its plants or its flowers etc …….

Thank you so much. The story actually makes more sense with oxen, doesn’t it? And thank you for providing the reference.