A few weeks ago, we received the following comment from Martin Nelson in England on our blog about Rooftops:

I am a singer, and lived briefly during 1982 in the Palais Royal district, Rue Molière… I had an old 1950 guide book with me – The People’s France – Paris by AH Brodrick – and this told me that … in Rue des Prêtres St Germain l’Auxerrois, was the original Café Momus, celebrated by [Henry] Murger in La Vie de Bohème, and the setting for Act Two of Puccini’s opera La Bohème. In 1982 it was still a café (but no longer Momus) and served the delivery van drivers for La Samaritaine, whose depot adjoined. I told the patron this tale, but it drew a complete blank; he had not heard of the opera, let alone his establishment’s celebrated history. In past times above the cafe, Mr Brodrick also informs me, was the ‘queer dingy little offices of the Journal des Débats which in its day occupied a unique position in European journalism.’ There. I wonder if this will set you off on a hunt…

Well, yes, Martin, it did.

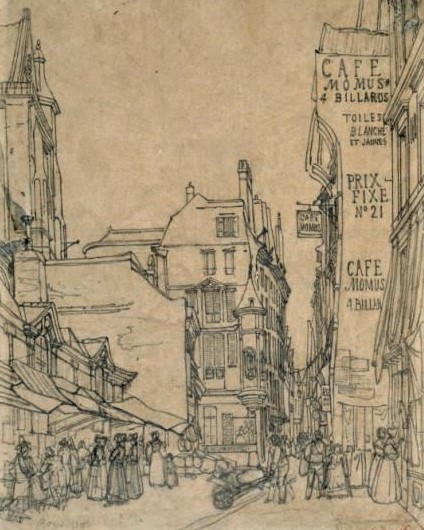

First, I wanted to take a look at the street in question. The earliest image I found was a drawing by the English artist Thomas Boys, which shows the street in about 1820. It looks like a bustling spot. The wall beside Momus, besides advertising its prix fixe menu and billiard tables, mentions “toiles blanches et jaunes,” which suggests a fabric shop in the same building.

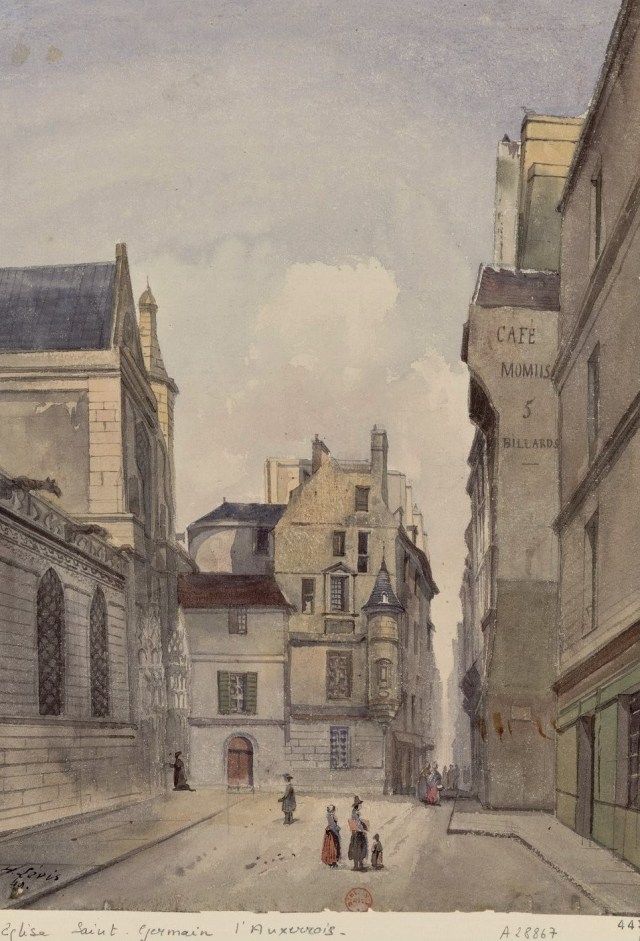

On Gallica I found a lovely watercolour of the narrow street by Henri Lévis from the late 1840s, around the time that Henri Murger wrote La Vie de Bohème.

Then I went to Google Street View to see what the spot looks like now. Actually, this image is a little older than 2021, because I wanted one that showed La Samaritaine (currently swathed in scaffolding). Note that the buildings on the left side of the street have been cleared away and that only the church buildings remain on that side, making the street much wider than it was.

One thing I could not find anywhere was a view of the cafe’s facade. Of course, it is a very narrow street. All the pictures I found show the end wall only, which at some point lost the upper part that curved outwards.

I also took a virtual walk down the street on Google Street View. The building that juts out on the right (on the wall of which the advertising was once posted and where there is now only a small green sign) is No. 19, and it is at present a hotel. Beyond it, as you walk towards La Samaritaine, is No. 17, the Clinique du Louvre, a private surgical facility with an arched doorway. Beyond that, at No. 15, is a very narrow building (only slightly wider than its front door), and at No. 13 is the Café l’Auxerrois.

Just to orient readers, here is a bird’s-eye view of the street from about 1920. This was after the buildings beside the church had been removed in 1912, but before the expansion of La Samaritaine later in the 1920s, which annexed the easternmost block of the street.

My next thought was to find a copy of Murger’s book. The 1883 English translation I found on Google Books was called The Bohemians of the Latin Quarter. I’m not sure why the translator added the last three words, since the Café Momus and many other locations are not in the Latin Quarter on the Left Bank, but on the Right Bank (one of the main characters, Rodolphe, lives in Montmartre, for example). Probably a decision by the publisher’s marketing department.

The café makes its first appearance on page 23, where we learn that Momus is “the god of play and pleasure.” (Actually, Momus is associated with satire. Martin tells me he was the god of mockery, expelled from heaven by Zeus for ridiculing the other gods.) The four main characters in Murger’s stories spend much of their time in this establishment.

Indeed, the café itself is the subject of Chapter XI, in which the proprietor complains to the four friends who frequent his upper floor that they are bad for business. They steal his newspapers, monopolize his backgammon board, use the place as a painting studio complete with models or as a noisy music room, make their own coffee instead of buying it from him, and corrupt the serving staff. All true. A truce is struck in which the bohemians agree to buy their coffee from him. This is quite a concession, because the one thing bohemians do not have is ready money.

Hosting bohemian artists has never been a lucrative enterprise. A non-fiction description of the Café Momus, written in 1862 by Alfred Delvau, in which the real-life characters include Murger himself and his friends, describes their way of saving money. One man would enter and order a coffee. The others would join his table one by one without ordering anything and share one little cup of coffee, four sugar cubes, and the accompanying glass of water.*

These stories remind me of the pre-pandemic days in which writers and freelance workers would settle into a café with a laptop and stay there for hours on end, having bought a single coffee. I always wondered how the proprietors stayed in business. It seemed a recipe for insolvency.

Apparently this was the case in mid-19th-century Paris, for in 1856 the Café Momus went out of business. In a notice from 1845, the place advertises billiards and newspapers among its amenities. Maybe the owners should have focused more on providing food and drink only.

The space then became an art-supply store (Colin, marchand de couleurs, at No. 19). When Charles Marville photographed the street in 1860s, Colin’s advertisement has replaced that of the Café Momus on the wall. There is also a little sign sticking out on the right side of the street that indicates that there was a pawnshop (Pelletier, Mont de Piété) in the building, too.

The art-supply store went out of business in its turn in 1890, around the time that a bust of Henry Murger was being installed in the Jardin du Luxembourg.

What about the other business Brodrick mentioned – the journal? It was time to rummage about in the Annuaire-Almanach du commerce, which lists all the businesses, first alphabetically, then grouped by type, then by address in Paris from 1857 to 1908 (this is a Gallica rabbit hole into which one can disappear for hours at a stretch).

As of the first issue, in 1857, the Journal des Débats is listed as the occupant of No. 17, the space next door to the former café. In 1870, Colin (and Pelletier, the pawnshop owner) are listed at No. 19 and the Journal (as well as Lenormant, a printer) are at No. 17. By 1908, No. 17–19 is the Imprimerie typographique du Journal des Débats, occupying both buildings.

So A. H. Brodrick was not quite right: it seems that the Journal des Débats was at first a next-door neighbour to the café, and later expanded, with its own printing facility, into the space vacated by the former café/art supply store. This conclusion is borne out by Alfred Delvau in 1862. Although the Café Momus had closed by the time Delvau wrote his book about Paris cafés, such was its fame that he devoted an entire chapter to its history, describing it as being “à un parpaing de l’imprimerie du Journal des Débats.” Un parpaing is a stone block, so I think that means next door.*

Here is a view from the late 19th century showing the façade of No. 17 – you can just see the word “Débats” over the arched doorway (which today forms the entrance to the clinic).

What was this “unique” journal?

It began in 1789 as a verbatim record of the debates of the Assemblée Nationale (think Hansard) and evolved into a general political and literary journal. It was published almost daily, usually with four pages of closely printed type. It survived the Revolution, as well as Napoleon (who insisted it call itself the Journal de l’Empire), the Restoration, the Second Empire, the Third Republic, and the better part of two world wars. It continued to operate during the Occupation, which presumably tainted its reputation, because at the Liberation in 1944, it ceased publication.

The next step was to figure out what took its place. This slightly out-of-focus photo from the late 1940s indicates that Nos. 17 and 19 had become a hotel called Le Pays (there is a different hotel at No. 21). Today the hotel at No. 19 is called Le Relais du Louvre.

If you want to take a closer look at the photograph above, go to this page, and zoom in.

So, Martin, I am compelled to conclude that the café you visited was what is now the Café l’Auxerrois at No. 13, an unpretentious brasserie that I can well imagine might cater to drivers for La Samaritaine, right across the road at that end of the street.

A look at the Annuaire shows that this space was not always a restaurant. Over the years it has served, among other things, as a wallpaper shop and a wine merchant’s premises.

Alas, the brasserie you visited in 1982 was not the inheritor of the illustrious mantle of the Café Momus. But when the Relais du Louvre reopens in May 2021 (it is currently closed because of the pandemic), perhaps you can reserve a room on the first floor. There you will be in the space once occupied by the bohemians.

Text by Philippa Campsie; historic illustrations from Gallica and the Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris; modern illustrations from Google Street View; photo of bust of Henry Murger from Wikipedia.

*Alfred Delvau, Cafés et Cabarets de Paris, Paris : E. Dentu, 1862. Mine is a modern facsimile copy from Maxtor, purchased at one of my favourite Paris bookshops, Pippa.

What a fascinating story! I have walked down this unassuming street many times and have had a coffee in the L’Auxerrois. Your blog has really brought it alive.

On our next visit, we are certainly going to L’Auxerrois for a glass of wine! Whenever that will be.

Thank you Philippa – that’s all I would have wished for, hoped for (but expected) from your researches. And thank you for posting on the Vernal equinox, which is a thing of mine… https://martinnelson.co.uk/equinox/.

What a narrow street! Opera choruses, when we are allowed to reconvene, should not complain of a crowded stage for the scene. The church gargoyles must be ‘modern’ then – or else they disgorged the rainwater into poor folks’ bedrooms in the houses abutting.

Many thanks for getting me started with an interesting question. Happy Equinox to you and your family!

Thank you for your lovely, beautifully researched writing, Philippa. Always interesting!

Thank you for the compliment. Writing the blog has helped keep me sane during the lockdowns.

Last month, I had some surgery in the “Clinic du Louvre”, wide, modern and anonymus.

The only seenable part of the antic building, is the beautiful large wooden 17th century bannister.

Sorry to hear about the surgery. I hope it all went well.

As always, great detective work. And I love your appraisal of bohemians as bad customers.

Honestly, who would want to cater to that crowd? They don’t pay and they scare away other customers!

Brava. Philippa! This is another extraordinary deep dive into a tiny sliver of Paris history, with your usual meticulous attention to history, architecture, and culture. I read many blogs from/about Paris, but your is always the most satisfying, not to mention informative. Thank you for your work.

Marsha Huff

Thank you for your kind words. If you yourself have any questions or challenges, let me know, so I can go hunting again!

Such fascinating sleuthing, Philippa! Great question from Martin Nelson. The distinctive street form, most likely by happenstance, with the long setback building then the jutting out, make it especially noticeable. I read avidly wondering if you’d come back to the Journal des Débats on the second floor. Then I realized I was mixing it up with Le Débat, a French intellectual review, which closed last summer (New York Times March 5, 2021). Its closure left the NYT opinion writer to wonder if French intellectual life had become too Americanized to support it?

The setback is an interesting feature. At one point in the 17th or 18th century, a ruling required that any building being demolished and rebuilt had to be set back by a certain amount. The idea was to widen streets over time. But of course, there were few cases in which whole streets were rebuilt (at least before Haussmann), so older streets often have just a few setbacks here and there. Also interesting about Le Debat. I don’t think I have read it.

Thanks for another fascinating trip into old Paris, I can’t wait to get back. What a great shame that wonderful tower was lost at the end of the street, that’s progress I guess 🙂

The charming little turret disappeared before the rest of the houses, for some reason. Eugene Atget took a picture around the turn of the century and the wall on the left is blank and dilapidated, the turret gone.

Very interesting Philippa! Another enjoyable wander through the past and present streets of Paris.

Absolutely fascinating. Thank you! Each time I see Puccini’s La Bohème I shall think of the real café Momus!

The opera was written in the 1890s, long after the cafe ceased to exist. Many opera companies stage it as if it took place in the 1890s, and it looks like something from Toulouse-Lautrec. There were still Bohemians in the 1890s, of course. But the original is from an earlier time, which I don’t think I fully appreciated until now.

What a wonderful article. It never occurred to me to look up the places where La Boheme is set. So interesting. Many thanks.

If it hadn’t been for Martin Nelson, it would not have occurred to me either! Glad you enjoyed the results.

That certainly is a striking picture of the street by Marville! So much story there. I very much enjoy your research, you get into all the corners!