Many of our blogs begin with a postcard. That is not a coincidence. When we are rummaging through the bins of 1- and 2-euro cards at flea markets, we are drawn to images that make us stop and wonder, “What is that? Where is that? Why is that?”

I can’t remember where or when I bought this particular postcard, postmarked 1904, showing an unusual view of the Seine, but it raised those questions and I decided it was time to put them to rest.

You can see the Pont des Arts in the background and the Louvre on the right bank. In the foreground is a basin with a few barges as well as a row of floating, shuttered structures on the right. A large concrete pier separates two areas of the basin. At the far end of the basin is a series of abutments, connected by what appears to be a metal catwalk. There is also something moored on the far side of the river. I got out my loupe and peered at it closely.

You can see the Pont des Arts in the background and the Louvre on the right bank. In the foreground is a basin with a few barges as well as a row of floating, shuttered structures on the right. A large concrete pier separates two areas of the basin. At the far end of the basin is a series of abutments, connected by what appears to be a metal catwalk. There is also something moored on the far side of the river. I got out my loupe and peered at it closely.

It resolved itself into a small barge connected to the shore by a footbridge, with a two-storey building behind it and steps leading down from the upper quai to the lower embankment. There were signs on the barge and I could just make out the word Guillout on one of them. I could see a person standing on an open area of the barge, perhaps another on the footbridge. Already I had lots of questions.

I found another view, postmarked 1925, this one showing the same scene, but from the other side, so probably taken from the Pont des Arts.

The basin and the concrete pier are there, with a collection of barges between the pier and the embankment and assorted other craft in the basin. Seen from this angle, the abutments have steps cut into them. The shuttered structures are still there, on the left, looking somewhat the worse for wear. The bridge in the background is the Pont Neuf and beyond it on the left is the tower of the Préfecture de Police on the Quai des Orfèvres. In the distant background are the buildings on the east side of the Place St-Michel.

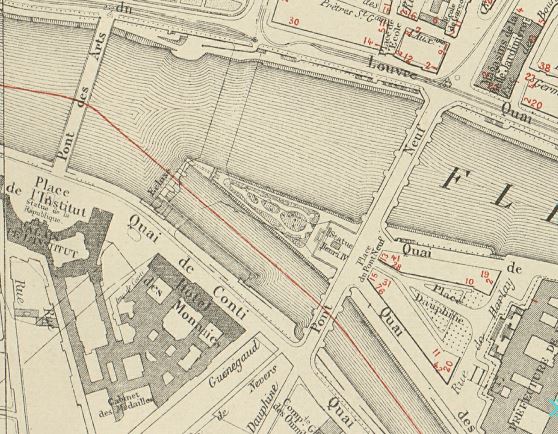

So far, so good. Having zeroed in on the location, I looked for a map. This took some time. Many maps provide exquisite detail of the land part of Paris, but very few showed details of the river. Finally, I found what I wanted in the Atlas municipal des vingt arrondissements de la ville de Paris, in a version dating from 1888 (the Atlas was updated every few years).

The map adds the word “écluse” or lock, and that provided the clue I needed. The lock was apparently known either as the Écluse de la Monnaie (the lock at the Monnaie or Mint – the nearest building on the Left Bank) or, less often, the Écluse du Pont Neuf.

But the map is somewhat inexact. The lock was the narrower part between the embankment and the concrete pier. The series of abutments between the Left Bank and the Ile de la Cité were part of a “barrage” or dam, known as the Barrage de la Monnaie. The whole thing was built in the early 1850s and remained in place until the 1920s.

It was part of a river control system. For centuries, goods entered Paris in bulk on a barge – coal, wood, wine, wheat, hay. But the Seine made an unreliable highway. Occasionally it froze in winter, and at other times the water level sank too low to allow for boats and barges.

Work in the first half of the 19th century on the Seine and its tributaries made the river easier to navigate. Dams and locks were constructed above and below Paris to control the flow. “Canalization” consisted of dredging, building up the banks on either side, and generally making the unruly river behave more like an obedient canal. (That is why the previous postcard has the words “Vers le canal” – this branch of the river had been made into a mini canal.) Meanwhile, new canals were built to bypass sections of the winding river entirely.

The “barrage éclusé” near the Monnaie allowed river traffic going upstream (east) to rise 1 metre during the trip through the city, making the journey easier for barges. Downstream traffic used the wider, unimpeded channel on the far side of the Ile de la Cité.

Finally, I found another postcard, postmarked 1907, clearly identifying the barrage. This image does not show the lock (out of sight on the right), but the much larger basin. Note the floating swimming school on the left, moored against the right bank. And the little pointy-topped structure at the end of the concrete pier.

Now look what happened during the flood of January 1910. This image is from Gallica. The pointy-topped structure is one of the few things poking up through the high water.

The flood was the beginning of the end for the lock and dam. Not only was the barrage damaged, but later efforts to prevent further floods made the lock redundant. The whole thing was finally demolished in 1924.

(By the way, in the flood photograph, what appear to be two spires on the far shore were part of the old Samaritaine department store. The scaffolding is probably from the enlargement of the store around this time. The white floating structure in front is the Bains de la Samaritaine – the Samaritaine baths – which eventually sank completely during the flood, leaving only the rooftop with its fake palm tree above the waves.)

But back to the original photograph. What about those floating, shuttered structures? A comparison with other Seine photographs on Paris en Images shows that they were bateaux-lavoirs – laundry boats – permanently moored beside the Square du Vert Galant at the downstream tip of the Ile de la Cité. Laundresses (lavandières) would bring piles of sheets and other laundry here for washing. There were many such barges up and down the river, but this central one was particularly large. And yes, the sheets were washed in river water (try not to think too hard about that). The shuttered openings could be raised to allow the laundresses direct access to the river.

As for the boat or barge on the far side of the river, I did some more squinting at it and decided that the large sign read “Exquise Goulliout.” A quick Google search explained this odd combination of words. Goulliout was the name of a biscuit manufacturer and exquises were a form of biscuit. It was an advertisement.

Another hunt through our postcard collection turned up a view of the Right Bank in this location with an indecipherable postmark. There are two barges, covered with advertisements, linked to the shore with footbridges, and two boats moored to the barges. The nearer one is filled with men in top hats and women with parasols. They are bateaux-omnibus or river buses and the barges linked to the shore served as the waiting rooms and ticket offices. My 1910 Baedecker indicates that the stop in this location served the Charenton–Auteuil line.

Finally, I examined the two-storey structure beyond the boat. I realized it was on what used to be called the “Quai du Louvre” (most of which is now called the Quai François Mitterand). I did a search for that name on Paris en Images and lo and behold, at the very bottom, I saw a photograph by Charles Marville: the Bureau des voitures à voie ferrée Vincennes-Sèvres.

Bureau des voitures à voie ferrée Vincennes-Sèvres, quai du Louvre. Menuiserie. Paris (Ier arr.), entre 1858 et 1878. Photographie de Charles Marville (1813-1879). Paris, musée Carnavalet.

“Voitures à voie ferré” (vehicles on iron rails) I take to be trams. This service linked the centre of Paris with the eastern (Vincennes) and western (Sèvres) suburbs. On Wikipedia, I found the same image labelled, “Bureau d’Omnibus de la Compagnie Générale, quai du Louvre.”

This is the view from the upper level of the quay; the lower part is invisible. But the original photograph showed steps going down to the lower level, so this would have been an interchange between the trams and the river buses. Makes sense.

Having satisfied my curiosity about the original postcard, I searched for other images of the locks and barrage. I think my favourite is this one from Gallica, showing the abutments being used as springboards for a women’s swimming competition in 1913. It also gives a sense of scale for the dam. It’s larger than it seemed in the first postcard.

I also found an oil painting of the lock, dated 1907, by Marie-Gabriel Biessy, showing the locks in the evening with the lights from the Pont Neuf sparkling on the water.

So now, if you happen to see an image like this…

…you will know what you are looking at. You’re welcome.

And if you have a mysterious Paris postcard or photograph image you cannot place, I’m willing to have a go at identifying it.

For more stories inspired by postcards, see “A palace of commerce and a 1904 rendez-vous,” “The postcard collector,” or “Postcards of a working river.”

Text by Philippa Campsie. Map from Portail des bibliothèques municipales spécialisées. Postcards from our collection. Photographs from Gallica and Paris en Images. Painting from Artnet.

Beautiful story, I loved it! Thanks for this travel back in time, and bravo for this fascinating investigation work. I’ll have another story to tell my kids when we walk by the quays of the Square du Vert Galant :), thank you for that!

Another reader thinks there may be a plaque about the old locks in the vicinity. Perhaps you and your kids can find it!

I think there is a plaque on the river wall near the Pont Neuf that relates to this lock. I photographed it but the inscription didn’t make any sense. Eventually we decided there must have been a bridge there once, but it could perhaps have been the lock.

I shall have a look for that next time I am nearby. Thanks.

Great post that took a lot of detective work!

Coming from you, with your wonderful investigations into the past, that is high praise indeed! Many thanks.

Great collection of Paris views.Cheers, Barney

Another fascinating blog. Many thanks for all your research and the lovely way you put it all together. Have you considered publishing them as Vignettes of Past Paris?

Perhaps I will one day. But it’s a crowded field! I am glad you enjoy the blog.

Hello,

As usual, a very interesting post! I always enjoy reading you. Just wanted to say artist Marie-Gabriel Biessy was a man.

[cid:e0d2a03a-4e7c-41d7-bfc5-c4dbd56e2dd3] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel_Biessy

Regards,

Linda Shan Jones

________________________________

Right you are! Well spotted. Thank you.

I save your posts the way I save the last piece of chocolate fondant…to be splurged on, when life is a challenge. I love the deep-dive research, and the way you take us on the journey with you. Thank you.

What a lovely thing to say! And it arrived on a day when I needed a bit of a morale boost! Thank you so much.